The elections held in India before its independence in 1947 marked critical milestones in the nation’s political history. These contests, initiated under British colonial rule, introduced Indians to the mechanisms of representative governance, albeit within a constrained framework designed to serve imperial interests. While they laid the groundwork for India’s eventual transition to democracy, they also sowed the seeds of division, polarization, and communal antagonism that culminated in the partition of the subcontinent. Understanding these elections in depth reveals their profound influence on India’s political awakening and the trajectory of its independence movement.

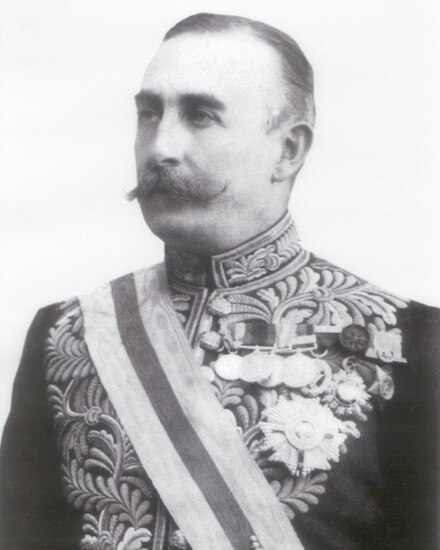

The Morley-Minto Reforms (1909): The Birth of Communal Politics

The first significant attempt to introduce electoral processes in colonial India came with the Indian Councils Act of 1909, commonly known as the Morley-Minto Reforms. This legislation expanded the role of Indians in legislative councils, allowing them to elect representatives to these bodies. However, the franchise was severely restricted to a small elite—landowners, businessmen, and educated individuals. The reforms were not motivated by a desire to democratize governance but rather to quell growing discontent against colonial rule and to incorporate a loyal section of Indian elites into the administration.

A key feature of the reforms was the introduction of separate electorates for Muslims, enabling them to elect their representatives independently of other communities. This provision institutionalized the political separation of Hindus and Muslims, laying the foundation for communal politics. While ostensibly designed to protect Muslim interests, it fragmented the burgeoning nationalist movement, creating a competitive political environment where communities vied for representation rather than uniting against colonial domination. Over time, the concept of separate electorates would profoundly impact the political landscape, reinforcing the notion that Hindus and Muslims constituted distinct political entities.

The elections under the 1909 reforms were limited in scope but marked the first time Indians participated in a form of electoral politics. However, these early experiments emphasized division rather than unity, as the British intentionally pitted communities against one another to maintain control. The communal cleavages introduced during this period would have long-lasting repercussions, contributing to the eventual partition of India.

The Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms (1919): Expanding Representation Amidst Resistance

The next major step in India’s electoral journey came with the Government of India Act of 1919, based on the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms. This legislation expanded provincial legislative councils and introduced a system of dyarchy, which divided provincial governance into “transferred” subjects (like health, education, and agriculture) controlled by Indian ministers and “reserved” subjects (like finance and law) retained by British officials. The reforms aimed to grant Indians limited self-governance while maintaining British supremacy.

The 1920 elections under this Act were the first to be held at a broader scale. Although the franchise was slightly expanded, it remained limited to property owners, taxpayers, and those with educational qualifications, thereby excluding the majority of the population. These restrictions revealed the colonial government’s reluctance to empower Indians fully. More significantly, the Indian National Congress (INC), under Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership, boycotted the elections as part of the Non-Cooperation Movement, protesting the inadequacy of the reforms and the colonial government’s refusal to grant full self-rule.

The Congress’s boycott resulted in low voter turnout, but it also exposed deep divisions within Indian society. While the INC advocated for mass non-cooperation, other political groups, including the Muslim League, participated in the elections, seeking incremental gains within the existing system. This divergence in strategy highlighted the growing gap between the Congress, which claimed to represent all Indians, and the Muslim League, which increasingly sought to assert Muslim identity and interests. The election outcomes reinforced the League’s belief that it needed to focus on securing political safeguards for Muslims, setting the stage for greater polarization in the decades to come.

The Simon Commission and the Communal Award: Institutionalizing Divisions

By the late 1920s, the inadequacies of the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms had become apparent, prompting the British to form the Simon Commission in 1927 to propose further constitutional reforms. The absence of any Indian members on the Commission led to widespread protests, uniting diverse groups under the banner of opposition. However, the response to these protests varied, with some leaders advocating for united opposition while others, including the Muslim League, used the opportunity to press for communal safeguards.

The aftermath of the Simon Commission included the Communal Award of 1932, which granted separate electorates not only to Muslims but also to other communities, including Sikhs, Dalits, and Anglo-Indians. While these measures were framed as efforts to ensure fair representation, they further fragmented Indian politics along communal lines. Dalits, under leaders like Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, sought to use this opportunity to secure greater political rights, while the Congress, under Gandhi, opposed separate electorates for Dalits, arguing that it would divide Hindu society. This disagreement created fissures within the nationalist movement, weakening the unified front against colonial rule.

The Elections of 1937: Congress Dominance and Muslim League Marginalization

The Government of India Act of 1935 represented the most significant constitutional reform before independence, introducing provincial autonomy and further expanding the electorate. The first elections under this Act, held in 1937, were a landmark event, with around 30 million Indians eligible to vote—though this was still only a fraction of the population. These elections marked a turning point in the political trajectory of both the INC and the Muslim League.

The INC emerged as the dominant political force, winning a majority in seven out of eleven provinces and forming ministries in key regions. Its success demonstrated its popularity and organizational strength but also created resentment among other political groups, particularly the Muslim League. The League performed poorly, winning only 109 out of 482 reserved Muslim seats and failing to form a government in any province. This failure exposed the League’s limited reach and fueled its narrative that Muslims were being sidelined in a Hindu-majority political system.

The Congress ministries’ tenure was marked by efforts to implement progressive policies, but it also alienated Muslims in many regions. Accusations of cultural insensitivity and the marginalization of Muslim interests provided Jinnah and the Muslim League with ammunition to argue that Muslims could not rely on Congress to protect their rights. This period saw the League transition from a peripheral organization to a mass movement advocating for the creation of Pakistan.

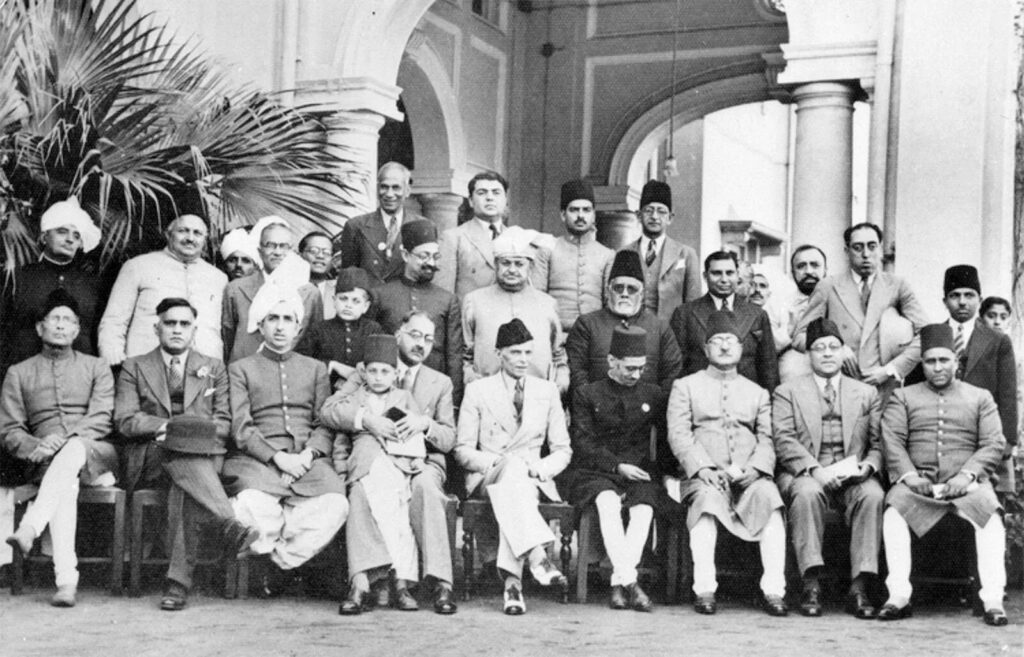

The Elections of 1946: The Final Step to Partition

The elections of 1946 were the last major electoral exercise before independence and were pivotal in determining India’s future. Held under the Cabinet Mission Plan, these elections were intended to elect members to the Constituent Assembly, which would draft the Constitution of a free India. However, by this time, the polarization between the INC and the Muslim League had reached its zenith.

The INC won 208 out of 296 general seats, while the Muslim League secured 73 out of the 80 seats reserved for Muslims, solidifying its position as the sole representative of the Muslim community. The League’s electoral success strengthened its demand for Pakistan, and Jinnah declared August 16, 1946, as Direct Action Day to mobilize support. This call led to communal riots, starting in Bengal and spreading across the country, resulting in widespread violence and loss of life.

The 1946 elections revealed the impossibility of reconciling the visions of the INC and the Muslim League for India’s future. While Congress sought a united India with a strong central government, the League insisted on partition to safeguard Muslim interests. The violence and political stalemate convinced the British that partition was inevitable, leading to the creation of India and Pakistan in 1947.

Conclusion: Democracy and Division

The elections held before India’s independence were transformative, introducing Indians to democratic processes and nurturing political leadership. However, they also exposed the fault lines within Indian society. From the communal electorates of 1909 to the polarized elections of 1946, these contests institutionalized divisions that undermined efforts to build a united nationalist movement. While they paved the way for democracy, they also contributed to the tragedy of partition, which left an indelible mark on the subcontinent.

The story of these elections is both an inspiration and a cautionary tale. It highlights the importance of inclusivity and unity in democratic systems and the dangers of communal politics in a diverse society. As India emerged from the shadow of colonial rule, it carried the lessons of these elections into its journey as the world’s largest democracy.