The Ahom Dynasty is one of the most influential and enduring regimes in the history of northeastern India. Spanning nearly 600 years, its legacy encompasses military genius, innovative administration, cultural synthesis, and economic advancements. This article brings together various facets of the Ahom experience—from their origins and rise to power, through their significant military campaigns, to the eventual decline that paved the way for British colonial rule.

Origins and Establishment

The Ahom Dynasty traces its roots to 1228 when Sukaphaa, a Tai prince from Yunnan (modern-day China), migrated with his followers into the Brahmaputra Valley. Seeking fertile land and a place to establish his rule, Sukaphaa initially encountered indigenous communities such as the Bodo-Kacharis, Morans, and Barahi. Rather than engaging in outright conquest, he used diplomacy and alliances to integrate these groups into his administration. Over time, his followers intermarried with the local population, creating a unique socio-political framework that blended Tai and Assamese traditions. This synthesis played a key role in the longevity of Ahom rule.

By the mid-13th century, Sukaphaa had firmly established Ahom control in upper Assam. His governance model allowed flexibility in administration while ensuring loyalty from different ethnic groups. Unlike earlier rulers who relied on feudal structures, the Ahoms introduced a more centralized governance system, which later became a defining feature of their rule.

Pre-Ahom Rule and the Transition of Power

The Pre-Ahom Landscape

Before the Ahoms emerged as the dominant power, the region was characterized by:

- Kamarupa Kingdom: Once a major center of power, the Kamarupa Kingdom had gradually fragmented into smaller local entities.

- Chutia Kingdom: In Eastern Assam, the Chutia Kingdom played a significant role in shaping the region’s political and cultural landscape.

How the Ahoms Ascended

- Migration and Settlement: The arrival of Sukaphaa and his people in 1228 marked the beginning of a transformative era. Initially, the Ahoms coexisted with local populations, but their superior military organization and administrative acumen soon set them apart.

- Conquest and Assimilation: By engaging in a series of military campaigns against local kingdoms—most notably the Chutia Kingdom—and integrating indigenous administrative practices, the Ahoms systematically expanded their territory. This gradual, multifaceted process of conquest and assimilation allowed them to consolidate power while minimizing resistance and fostering cultural integration.

Political and Administrative Innovations

Centralized Administration and the Paik System

A critical aspect of the Ahoms’ success was their well-organized administration. The king, or Swargadeo, was the supreme authority, assisted by high-ranking officials such as the Borgohain and Borpatrogohain, who oversaw military and administrative affairs. The kingdom was divided into multiple provinces or mauzas, each governed by appointed officials who ensured efficient governance.

One of the most remarkable features of Ahom administration was the Paik system, a unique form of military and labor conscription. Every adult male was registered as a Paik, assigned to serve in military or civil roles on a rotational basis. This system allowed the kingdom to maintain a large standing army while also ensuring sufficient manpower for state projects such as infrastructure development, irrigation works, and agriculture. The Paik system not only strengthened the military but also contributed to the kingdom’s economic stability by ensuring large-scale public works were consistently maintained.

Diplomatic Integration

As the Ahoms expanded, they often absorbed conquered peoples by integrating local chiefs into their administrative framework. This policy of assimilation helped smooth the transition from older indigenous systems to the centralized Ahom rule while maintaining social cohesion.

Military Prowess and Wars

The Ahom Dynasty is renowned for its military capabilities, reflected in several key conflicts that defined its history.

Wars Against Local Indigenous Kingdoms

Before the Ahoms arrived, Assam was a mosaic of small kingdoms and tribal territories, remnants of the once-powerful Kamarupa Kingdom. As Sukaphaa’s people settled in the region, conflicts arose:

- Chutia Kingdom Confrontation: The Chutia Kingdom, prominent in Eastern Assam, was one of the major local powers. The Ahoms launched military campaigns aimed at securing the fertile lands and trade routes of the region. The result was a gradual annexation of Chutia territories, accomplished through both military force and diplomatic assimilation.

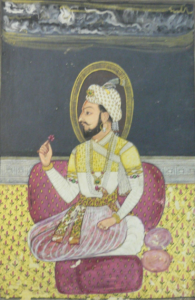

Confrontations with the Mughal Empire

The Ahoms also faced external threats, most notably from the expansionist Mughal Empire:

- The Battle of Saraighat (1671): This decisive naval battle on the Brahmaputra River stands as a symbol of Assamese resistance. Under the leadership of General Lachit Borphukan, the Ahom forces repulsed a much larger Mughal army. This victory was critical in halting Mughal ambitions in the northeast and safeguarding Assamese autonomy.

- Additional Incursions: Beyond Saraighat, the Ahom kingdom encountered several Mughal skirmishes. Although the Mughal forces were powerful, the Ahoms’ intimate knowledge of the local terrain and effective military strategies consistently turned the tide in their favor.

Wars with the Burmese

In the early 19th century, internal weaknesses and succession disputes left the Ahom state vulnerable:

- Burmese Invasions (1817–1826): The Konbaung dynasty of Burma, driven by expansionist policies, exploited this vulnerability. Burmese armies inflicted severe damage on the Ahom military and administrative structures, leading to widespread devastation. The culmination of these conflicts was marked by the signing of the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826, which ended Burmese aggression and set the stage for the British annexation of Assam.

Society, Culture, and Religious Syncretism

Over the centuries, the Ahoms fostered a distinctive culture that blended their Tai heritage with Assamese traditions. This fusion influenced various aspects of life, including language, rituals, and art.

The Ahoms were meticulous record-keepers, preserving their history in Buranjis, a unique genre of historical chronicles written in the Ahom and later Assamese languages. These texts provide valuable insights into the kingdom’s administration, warfare, and socio-economic conditions.

Religious evolution was another hallmark of Ahom rule. Initially practicing animism and ancestor worship, the Ahoms gradually assimilated Hindu and Buddhist elements into their belief system. Temples and shrines dedicated to both Ahom deities and Hindu gods became common, reflecting this religious synthesis. This policy of religious tolerance contributed to Assam’s cultural diversity and strengthened the cohesion of its multi-ethnic society.

Economic and Agricultural Contributions

The Ahom economy was primarily agrarian, with rice cultivation forming the backbone of economic activity. Recognizing the importance of agriculture, the Ahoms implemented advanced irrigation techniques, including the construction of reservoirs, canals, and embankments, ensuring year-round cultivation. These innovations not only increased agricultural productivity but also helped sustain a growing population.

Trade and commerce flourished under Ahom rule, facilitated by well-developed trade routes that connected Assam to neighboring regions such as Bengal, Bhutan, and Myanmar. The kingdom traded in goods like silk, betel nut, ivory, and horses, which contributed to its prosperity.

Additionally, the Ahoms invested in metalworking and craftsmanship, producing high-quality weapons, tools, and ornaments. The kingdom’s ability to manufacture durable arms contributed to its military resilience, while its artisans enriched Assam’s cultural landscape with exquisite handicrafts and textiles.

Decline and Lasting Legacy

Despite centuries of successful governance, the Ahom Dynasty eventually succumbed to multiple challenges. Internal succession disputes weakened central authority, while regional uprisings created instability. The repeated Burmese invasions in the early 19th century severely crippled the kingdom, making it vulnerable to external control.

The final blow came with the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826, following the Anglo-Burmese War. With the British emerging victorious, Assam was annexed into the expanding British colonial empire, bringing an end to six centuries of Ahom rule.

However, the Ahoms left an enduring legacy that continues to shape Assamese identity today. Their contributions to administration, military strategy, agriculture, and cultural heritage remain deeply embedded in Assam’s history. Many Ahom traditions, from language and literature to festivals and religious practices, persist in modern Assamese society. The legacy of leaders like Lachit Borphukan continues to inspire generations, and institutions in Assam commemorate their contributions through educational and cultural initiatives.

The Ahom Dynasty was a defining force in the history of Assam and northeastern India. From its establishment by Sukaphaa in the 13th century to its remarkable military achievements and governance models, the dynasty played a critical role in shaping the region’s cultural and political landscape. Even though its rule ended with British annexation, the impact of the Ahoms remains deeply embedded in Assamese identity, making them one of the most significant dynasties in Indian history.

Today, the legacy of the Ahom Dynasty is celebrated in the rich cultural traditions of Assam, and their historical chronicles continue to inspire scholarly research. Their story is a testament to the power of resilience, adaptability, and the ability to forge a unified identity from diverse cultural threads.