Wootz steel represents a seminal achievement in early metallurgical science, distinguished by its unique microstructure and superior mechanical properties. Developed in the Indian subcontinent as early as the 6th century BCE, this high-carbon steel gained international renown for its exceptional hardness, resilience, and ability to maintain a sharp edge.

Notably, Wootz steel served as the foundational material for Damascus swords, which exhibited an extraordinary combination of strength and aesthetic appeal. This discourse explores the origins, production methodologies, material characteristics, archaeological discoveries, and the broader influence of Indian scientific and metallurgical advancements.

Historical Origin and Development

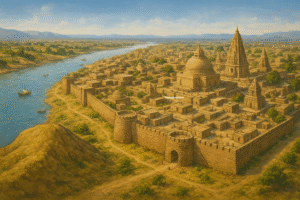

The genesis of Wootz steel is firmly rooted in the metallurgical traditions of South India, particularly in present-day Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka. Archaeological excavations reveal that ironworkers of the Maurya and Gupta periods had already mastered techniques of producing crucible steel, a sophisticated form of high-carbon steel.

In ancient India, Wootz steel was known as “Ukku” (ಉಕ್ಕು in Kannada), “Hindvi Steel,” or “Pulad” (فولاد in Persian, borrowed from Sanskrit “Pulinda”). The term “Wootz” is not originally from any Indian language but is believed to be an anglicized version of the Tamil and Telugu word “Ukku” (உக்கு in Tamil, ఉక్కు in Telugu), which means steel.

This high-quality crucible steel was highly sought after and was used to make legendary Damascus swords, which were known for their strength and unique patterns. Indian blacksmiths mastered the technique of producing Wootz steel as early as 300 BCE. This advanced metallurgical knowledge was transmitted through trade networks to regions such as Persia and the broader Middle East, ultimately influencing European metallurgical developments. The steel was transported as ingots to major forging centers where artisans transformed it into weapons of remarkable durability and sharpness.

Metallurgical Synthesis and Processing

The production of Wootz steel entailed a sophisticated crucible steel-making process, necessitating precise control over raw materials, furnace conditions, and cooling rates. The procedural methodology included the following stages:

- Raw Material Selection: High-purity iron ore, typically extracted from specific Indian mining regions, was combined with carbonaceous materials such as charcoal and organic substances that facilitated the diffusion of carbon into the metal matrix.

- Crucible Furnace Treatment: The iron-carbon mixture was placed within refractory clay crucibles and subjected to prolonged high-temperature treatment (1,300–1,400°C). This facilitated complete carburization and homogenization, yielding a steel ingot of uniform composition.

- Controlled Cooling Regime: The cooling phase was meticulously regulated to induce the formation of carbide banding, a microstructural feature that contributed to the steel’s distinctive watered pattern and mechanical superiority.

- Forging and Thermomechanical Processing: The ingots were subsequently forged at elevated temperatures, where skilled blacksmiths employed iterative cycles of heating and hammering to enhance ductility and refine the steel’s grain structure.

Structural and Mechanical Properties

Wootz steel exhibits several remarkable properties attributable to its precise composition and thermomechanical processing:

- Elevated Carbon Content: Typically containing 1–2% carbon, Wootz steel straddled the boundary between high-carbon steel and cast iron, optimizing both hardness and malleability.

- Superior Toughness and Fracture Resistance: Unlike conventional steels of comparable hardness, Wootz steel demonstrated enhanced toughness due to its lamellar microstructure, mitigating brittle fracture.

- Exceptional Edge Retention: The steel’s ability to sustain a sharp edge over prolonged use rendered it highly desirable for weaponry and fine cutting instruments.

- Microstructural Uniqueness: The presence of thermodynamically stable carbide nanostructures imparted the characteristic ‘Damascene’ pattern, which was not merely ornamental but functionally reinforced the material’s wear resistance.

Archaeological Evidence and Surviving Artifacts

Numerous artifacts and weapons forged from Wootz steel have been discovered in archaeological contexts, attesting to its widespread use and historical significance. Some of the most notable surviving examples include:

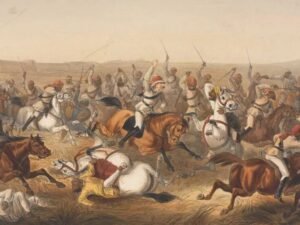

- The Sword of Tipu Sultan: This legendary blade, now housed in museums, exemplifies the high-quality Wootz steel weapons produced in India. It showcases the intricate mechanical properties and craftsmanship associated with Indian metallurgy.

- Damascus Blades: Many surviving Damascus swords, housed in European and Middle Eastern collections, have been confirmed through metallurgical analysis to have originated from Indian Wootz steel ingots.

- Excavations at Kodumanal and Arikamedu: Archaeological sites in Tamil Nadu have yielded iron and steel artifacts, providing insight into early Indian metallurgical traditions.

The Damascus Connection: Influence on Swordsmithing

The historical association between Wootz steel and Damascus blades is well-documented. The latter, crafted in the Middle East from imported Wootz ingots, were esteemed for their remarkable sharpness and resilience. Damascus swords, renowned for their capability to sever conventional blades and even slice through silk mid-air, became emblematic of superior metallurgy.

The precise mechanisms responsible for the superior performance of Damascus steel remained elusive for centuries, prompting numerous attempts at reverse engineering. It is now understood that the interplay between carbon nanotube-like structures and carbide dispersions contributed to the unparalleled performance of these blades.

Indian Scientific and Metallurgical Advancements

India’s metallurgical innovations extended beyond Wootz steel, encompassing a broad spectrum of scientific advancements:

- Iron Pillar of Delhi: This remarkable rust-resistant iron pillar, dating back to the Gupta period (circa 400 CE), exemplifies ancient India’s advanced understanding of corrosion-resistant iron alloys.

- Zinc Distillation: India was among the first civilizations to master the distillation of zinc, a critical step in the production of brass.

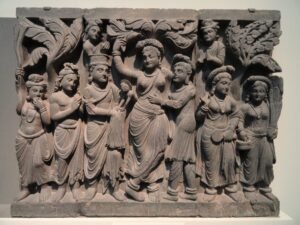

- Temple Alloys and Bronze Casting: The Chola dynasty (9th–13th century CE) pioneered the lost-wax casting technique, producing exquisite bronze idols that remain unparalleled in craftsmanship.

- Astronomical Instruments: Indian scientists, such as Aryabhata and Bhaskara, contributed significantly to applied sciences, integrating metallurgy with astronomical instrumentation.

Decline and Contemporary Reappraisal

The decline of Wootz steel production in the 18th and 19th centuries was precipitated by multiple factors: the erosion of artisanal knowledge, depletion of critical raw materials, and the ascendancy of modern industrial steel-making techniques. Despite persistent European efforts to replicate its microstructure, full-scale industrial reproduction remained elusive.

In contemporary metallurgical research, renewed interest in ancient steel-making practices has driven experimental reconstructions of Wootz steel. Advanced analytical techniques, including electron microscopy and spectroscopic analysis, have provided insights into its unique phase transformations, offering potential applications in high-performance materials engineering.

Wootz steel exemplifies the pinnacle of pre-modern metallurgical science, demonstrating a level of sophistication that continues to inspire materials research. Its enduring legacy spans centuries, influencing both the evolution of high-performance steels and the scientific understanding of phase-structured materials. The broader advancements in Indian metallurgy, from rust-resistant iron pillars to zinc distillation, underscore the subcontinent’s profound contributions to global science and technology. While the original methods of Wootz steel production may have been lost, the fascination surrounding its properties ensures that it remains an enduring subject of academic and industrial inquiry.