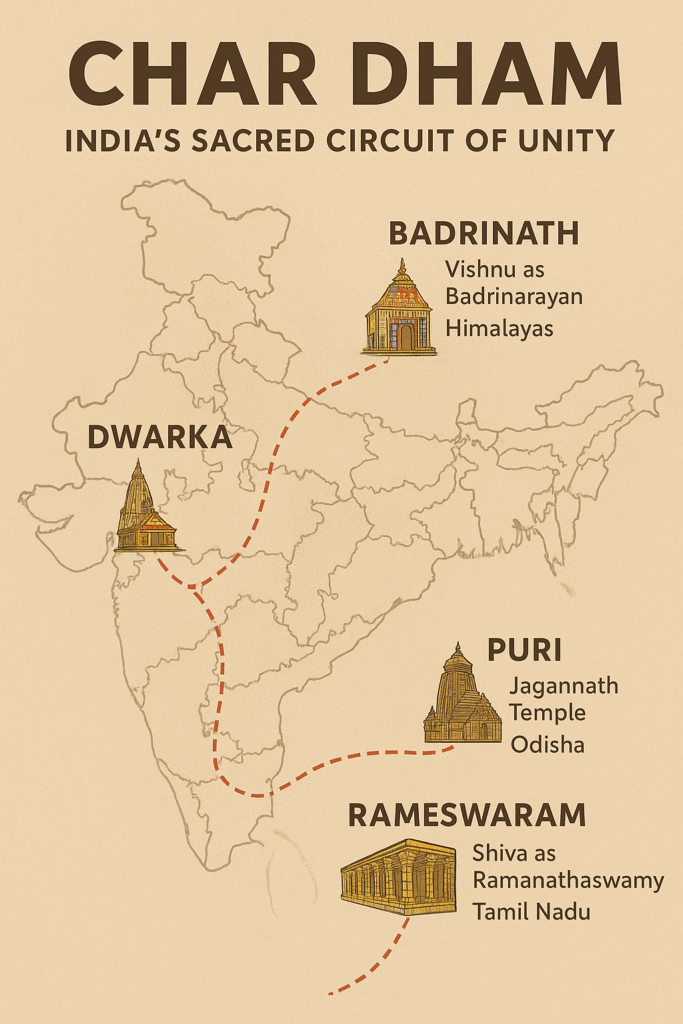

The Char Dham — Badrinath (North), Dwarka (West), Puri (East), and Rameswaram (South) — is more than a route for devout Hindus. It’s a centuries-old spiritual circuit that has shaped India’s religious geography, sustained cultural exchange, and anchored a shared civilizational identity.

Origins: Shankaracharya’s Vision

The concept of the all-India Char Dham is credited to Adi Shankaracharya (8th century CE), the philosopher-saint who traveled from Kerala to Kashmir, revitalizing Hinduism at a time of political fragmentation and doctrinal disputes.

His genius lay in linking four far-flung shrines, each representing a different form of the divine, into a single spiritual itinerary. This was both a religious revival and a subtle nation-building exercise, centuries before India became a political entity.

Badrinath (North) – dedicated to Vishnu as Badrinarayan, set in the Himalayas of present-day Uttarakhand.

Dwarka (West) – the coastal kingdom of Krishna, in Gujarat.

Puri (East) – home to Jagannath, a form of Vishnu, in Odisha.

Rameswaram (South) – a sacred Shaivite site in Tamil Nadu linked to Rama’s journey in the Ramayana.

The Four Corners of the Sacred Map

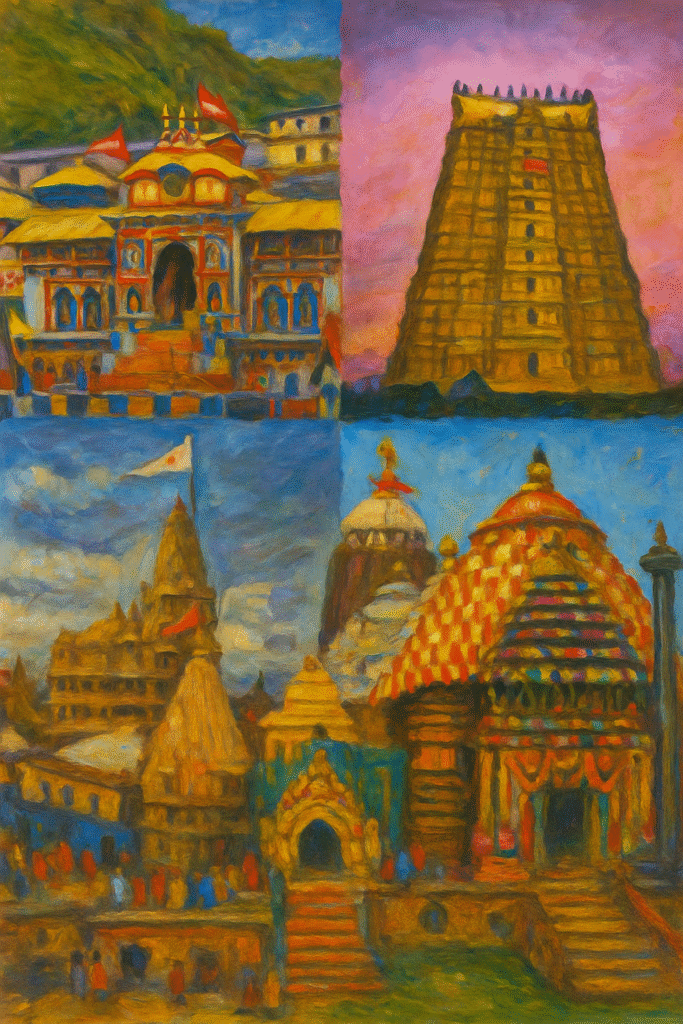

Badrinath – The Northern Pinnacle

- Deity: Vishnu as Badrinarayan.

- Legend: According to the Vishnu Purana, Vishnu meditated here in the form of a yogi, while Lakshmi shielded him from snow as a Badri tree.

- Architecture: The temple’s colorful façade, with its garuda-topped tower, reflects North Indian Nagara style, rebuilt multiple times after avalanches and earthquakes.

- Cultural Note: The site blends Pahadi folk traditions with Sanskritic ritual, and during winter, the idol is ceremonially moved to Joshimath.

Dwarka – The Western Gateway

- Deity: Krishna as Dwarkadhish (“Lord of Dwarka”).

- Legend: Dwarka is said to have been Krishna’s capital, built on reclaimed land from the sea. The Mahabharata describes its golden walls and bustling ports.

- Architecture: The main temple’s towering shikhara rises 51 meters, topped by a flag changed thrice a day — a practice kept alive for centuries.

- Cultural Note: Dwarka has been a hub for trade, maritime culture, and Vaishnavite scholarship, with strong ties to the Gujarat coast’s fishing communities.

Puri – The Eastern Shore

- Deity: Jagannath, a form of Vishnu, along with siblings Balabhadra and Subhadra.

- Legend: The wooden idols are ritually replaced every 12–19 years in a sacred renewal ceremony (Nabakalebara). The temple is central to the annual Rath Yatra, mentioned in medieval Odia poetry and devotional songs.

- Architecture: A monumental example of Kalinga architecture, with a curvilinear shikhara and intricately carved stone walls depicting scenes from epics.

- Cultural Note: Puri’s kitchen is one of the largest in the world, feeding thousands daily; it is also a melting pot where caste restrictions are suspended during the Mahaprasad meal.

Rameswaram – The Southern Anchor

- Deity: Shiva as Ramanathaswamy.

- Legend: In the Ramayana, Rama is said to have built a bridge (Setu) from here to Lanka to rescue Sita, and worshipped Shiva before his campaign.

- Architecture: Famous for its 1,200-meter-long corridors lined with carved pillars – the longest in any Hindu temple. The 22 sacred wells (theerthams) within the temple are central to purification rites.

- Cultural Note: Rameswaram merges Tamil Shaivism with Ramayana devotion, attracting both Shaivites and Vaishnavites.

Scriptural and Historical References

Texts like the Skanda Purana and Padma Purana refer to the spiritual merit of visiting these tirthas. Shankaracharya himself established monasteries (mathas) near each site – Jyotirmath (Badrinath), Sharda Math (Dwarka), Govardhan Math (Puri), and Sringeri Math (near Rameswaram) – creating centers of learning that endure to this day.

A Cultural Bridge Across India

For over a millennium, the Char Dham has brought together pilgrims from every linguistic, ethnic, and social background. Along the way:

- Merchants exchanged goods and stories.

- Poets composed devotional songs in regional languages.

- Temple arts — from Odissi dance in Puri to folk ballads in Dwarka – traveled and evolved.

The pilgrimage corridors became arteries of cultural exchange, uniting a vast land through shared ritual and hospitality.

Transformation Through Time

Historically, the Char Dham was a multi-year undertaking, demanding both physical stamina and deep faith. Modern transport has shortened the journey, but its spiritual depth remains. Today, some pilgrims still walk sections of the route, while others combine it with other regional pilgrimages, weaving personal meaning into an ancient map.

Why It Endures

The Char Dham is not merely about four temples. It is a moving affirmation of the Hindu worldview – that the divine is everywhere, accessible to all, and experienced differently in each land and culture. It is also a reminder that in India, unity is not uniformity, but the weaving together of countless local colours into one sacred fabric.