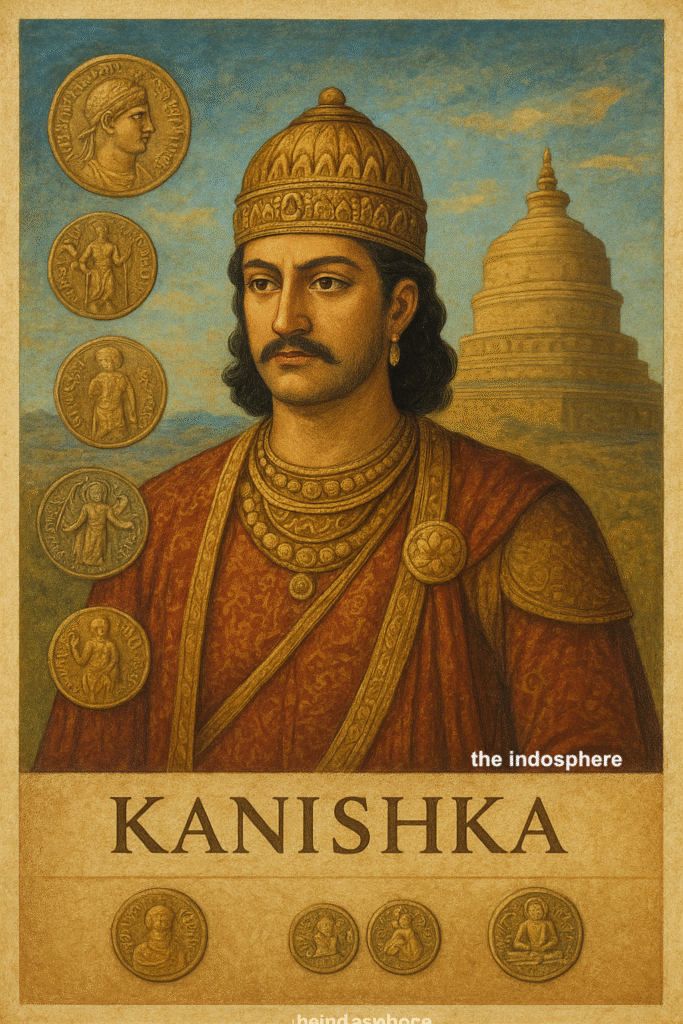

When we think of the great rulers of the subcontinent, names like Ashoka, Chandragupta Maurya, and Akbar dominate the imagination. Yet among them stands another figure, often less remembered but equally transformative: Kanishka the Great (c. 127–150 CE). A Central Asian nomad by origin, Kanishka not only ruled India but also left an indelible mark on its religion, art, and culture. His reign turned the Kushan Empire into a bridge between East and West, and his patronage of Buddhism shaped the future of Asia.

From Steppe to Throne

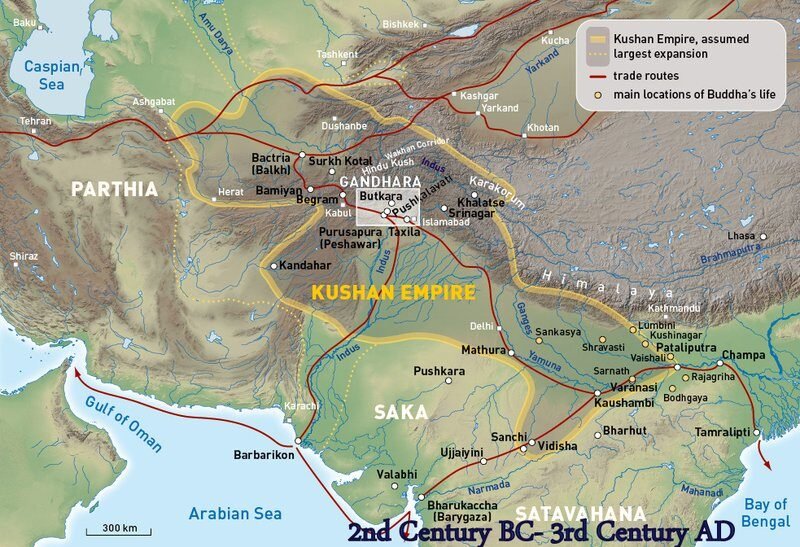

The Kushans were originally part of the Yuezhi confederation, nomadic peoples from Central Asia who migrated westward after being displaced by the Xiongnu. By the 1st century CE, they had settled in Bactria (Afghanistan and Central Asia), carving out an empire that stretched into northern India.

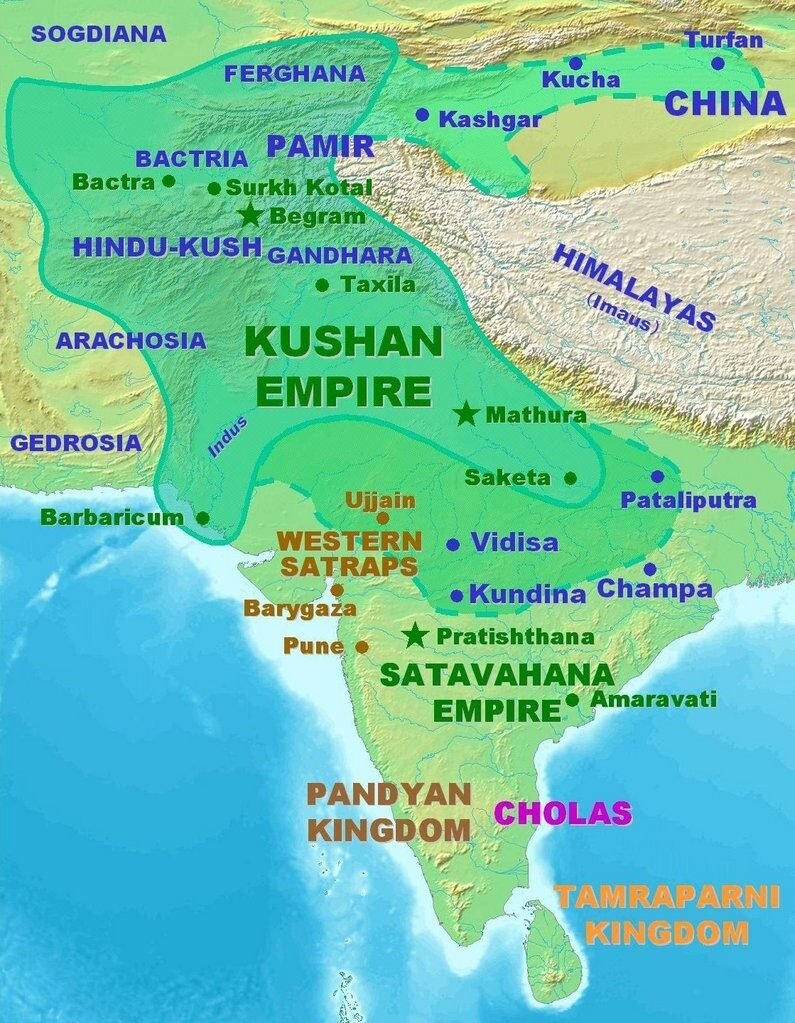

Kanishka, the most famous Kushan ruler, was likely the grandson of Vima Kadphises, who had already extended Kushan power into the Indian subcontinent. Upon his accession (around 127 CE), Kanishka inherited an empire that straddled Central Asia and India, but under his rule, it became truly vast — stretching from Samarkand and Bactria in the north to Mathura and Varanasi in the south, and from the Persian frontier to Bengal in the east.

For a man born outside India, Kanishka’s embrace of its culture was striking. His court language became Prakrit, and Sanskrit gained prominence during his reign. His coins and inscriptions appear in Greek, Bactrian, and Kharosthi, reflecting both his Central Asian roots and his Indian adaptation.

Capitals of Power: Purushapura and Mathura

Kanishka established his chief capital at Purushapura (modern-day Peshawar, Pakistan), making it the political and cultural hub of his empire. Here, he commissioned his most ambitious monument — the colossal Kanishka Stupa, described by Chinese pilgrims as rising nearly 700 feet, adorned with gilded copper. It was a beacon for Buddhist pilgrims across Asia.

His secondary capital at Mathura played a different role. Already a sacred city in Indian tradition, Mathura under Kanishka became a thriving artistic and religious center, where Mathura art developed alongside Gandhāra art. Together, these schools revolutionized the way gods and the Buddha were represented, with Mathura favoring more symbolic and indigenous styles while Gandhāra drew on Greco-Roman realism.

The Buddhist Emperor

If Ashoka had been the first great imperial patron of Buddhism, Kanishka was the second. His reign marked the moment when Buddhism transformed from an Indian religion into a world religion.

- He convened the Fourth Buddhist Council in Kashmir, traditionally dated to his reign. At this gathering, Buddhist monks codified and commented on texts, especially those of the Mahayana school.

- Mahayana Buddhism — with its emphasis on the Bodhisattva ideal, compassion, and universal salvation — gained prominence and spread rapidly along the trade routes supported by Kushan power.

- Missionaries carried Buddhism from Kanishka’s domains into Central Asia, China, and beyond. Without his patronage, Buddhism may never have become the global tradition it is today.

Kanishka’s Buddhist devotion was matched by his religious tolerance. His coins depict not only the Buddha but also Hindu gods like Shiva and Skanda, Zoroastrian deities like Mithra, and even Greek gods such as Helios and Selene. This eclecticism reflects the plural world of the Kushan Empire — and a king willing to embrace it all.

The Face of the Empire: Coins and Culture

Kanishka’s coinage is one of our richest sources about his reign. Struck in gold, silver, and copper, his coins depict him in Central Asian attire — heavy boots, thick coat, sword at his side — a reminder of his nomadic origins. Yet the reverse shows a pantheon of gods, Indian and foreign, making his coins miniature cosmologies of his empire.

His inscriptions also reveal the evolution of language in India. The Rabatak inscription, found in Afghanistan, records his adoption of Bactrian written in Greek script, but also his embrace of Indian titles and epithets. He is styled Shaonanoshao Kanishki Koshano — “King of Kings, Kanishka the Kushan.”

Kanishka and Gandhāra: Art as Empire

Perhaps the most lasting cultural achievement of Kanishka’s reign was the flowering of Gandhāra art. In the workshops of Gandhāra (northwest India and Pakistan), sculptors fused Greco-Roman techniques with Indian religious themes.

For the first time, the Buddha was represented in human form — draped in robes, serene-faced, with the calm majesty of an Apollo. This innovation, encouraged by Kanishka’s patronage, became the template for Buddhist art across Asia. From Afghanistan’s Bamiyan Buddhas to the caves of Dunhuang in China and the temples of Japan, echoes of Gandhāra can be traced.

In Mathura, by contrast, the Buddha and other deities were portrayed in more robust, indigenous styles. Together, these two schools created a visual language that defined Indian art for centuries.

The King Who Bridged Civilizations

Kanishka’s empire was a civilizational crossroads. Merchants carried silk, spices, and gems across his territories; monks carried scriptures and images; ideas flowed in every direction. His reign coincided with the height of the Silk Road, and his empire became its beating heart.

For this reason, historians often call Kanishka a world emperor. Though foreign-born, he was as Indian a ruler as any — adopting its languages, worshipping its gods, patronizing its religions, and leaving behind monuments and cultural achievements that enriched its civilization.

Decline and Memory

After Kanishka’s death, the Kushan Empire gradually weakened, pressured by the rising Sassanian Persians in the west and the Guptas in India. But his memory endured. In Buddhist tradition, he was remembered almost like a second Ashoka, a monarch who spread the Dharma. In art history, his patronage ushered in one of the greatest ages of creativity.

Today, Kanishka remains a symbol of India’s ability to absorb and transform — to take a foreign-born ruler and make him a champion of its culture. He stands as a reminder that identity in the ancient world was never static, and that some of India’s greatest rulers were those who, though outsiders, became insiders through vision, patronage, and faith.