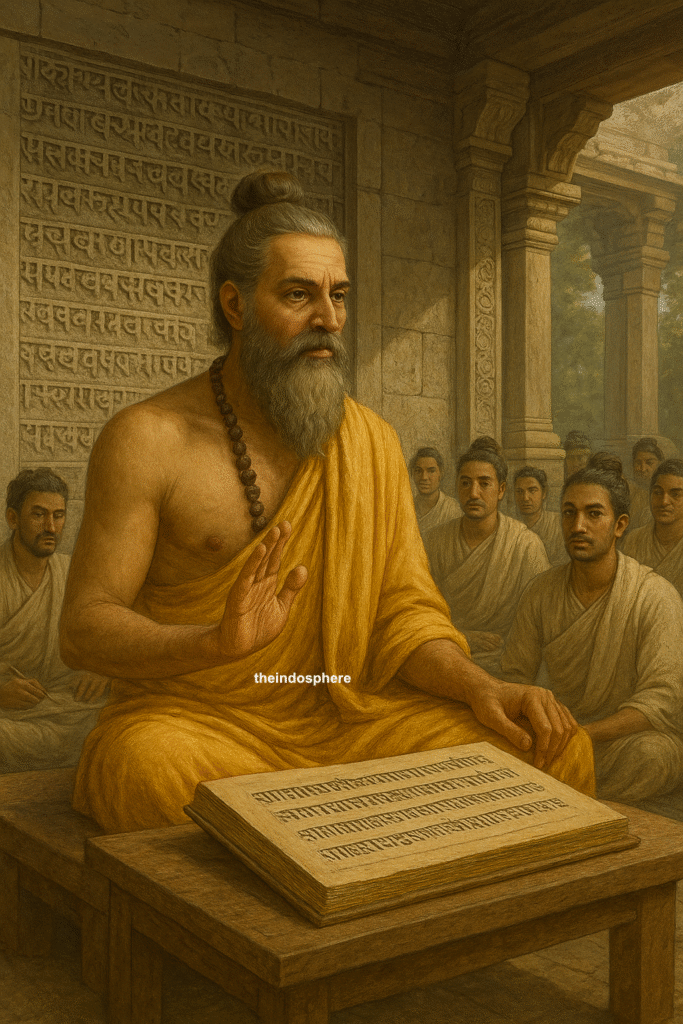

Among the great intellectuals of ancient India, few figures stand as tall as Panini. While kings and conquerors left monuments that weathered and crumbled, Panini left behind a work of pure thought: the Ashtadhyayi, an eight-chapter treatise on Sanskrit grammar. Written in the 5th–4th century BCE, it remains the most advanced linguistic system of the ancient world, anticipating concepts that would only re-emerge in modern times.

The World of Panini

Panini was born in Shalatura, a settlement in the region of Gandhara, near the banks of the Indus River (modern-day northwestern Pakistan). Gandhara was a cultural melting pot, lying at the junction of India, Persia, and Central Asia.

- To the west, the Achaemenid Empire had extended its influence, and Persian administrators and soldiers passed through these lands; leaving traces in administration and vocabulary, some of which Panini carefully recorded.

- To the northwest, the Khyber Pass linked Gandhara with Bactria and beyond.

- To the east, the Gangetic plains were home to rising powers like Magadha.

- Just nearby, Taxila stood as one of the world’s earliest universities, a hub where philosophy, law, medicine, and the Vedic sciences were taught.

Panini’s intellectual environment was cosmopolitan, absorbing influences from Vedic traditions as well as contact with foreign cultures. His work reflected both the rootedness of Sanskrit and the openness of Gandhara’s frontier world.

The Ashtadhyayi: Eight Chapters of Precision

The Ashtadhyayi is unlike any other ancient text. Rather than a descriptive narrative, it is a system of nearly 4,000 sutras (aphoristic rules), each compressed into a few syllables, yet designed with mathematical exactness.

- Algorithmic Structure: Each rule builds upon the other, forming a generative grammar where correct words and sentences can be derived step by step.

- Universal Scope: Panini did not simply describe Sanskrit — he designed a system that could produce all its forms.

- Self-Referential Logic: His rules created a meta-language, defining and applying terms within the system itself.

In modern terms, the Ashtadhyayi functions like a computer program. With a finite number of instructions, it generates infinite possibilities. This is why many computer scientists today consider Panini the earliest precursor to formal language theory.

Language and Society in Panini’s Era

The India of Panini’s day was marked by linguistic diversity. Sanskrit, the language of the Vedas and rituals, was preserved and revered by the learned elite. At the same time, Prakrits — vernacular dialects of everyday people — flourished across the subcontinent.

Panini was deeply aware of this divide. His grammar:

- Preserved sacred Sanskrit in its pure form for ritual and scholarship.

- Acknowledged vernaculars and borrowings, even including foreign words (notably Persian terms), reflecting Gandhara’s cosmopolitan environment.

Thus, the Ashtadhyayi is not only a grammatical system but also a cultural document, capturing a snapshot of India at the crossroads of tradition and change.

The Commentators: Building on Panini

Panini’s brilliance was recognized quickly, and generations of scholars extended his work:

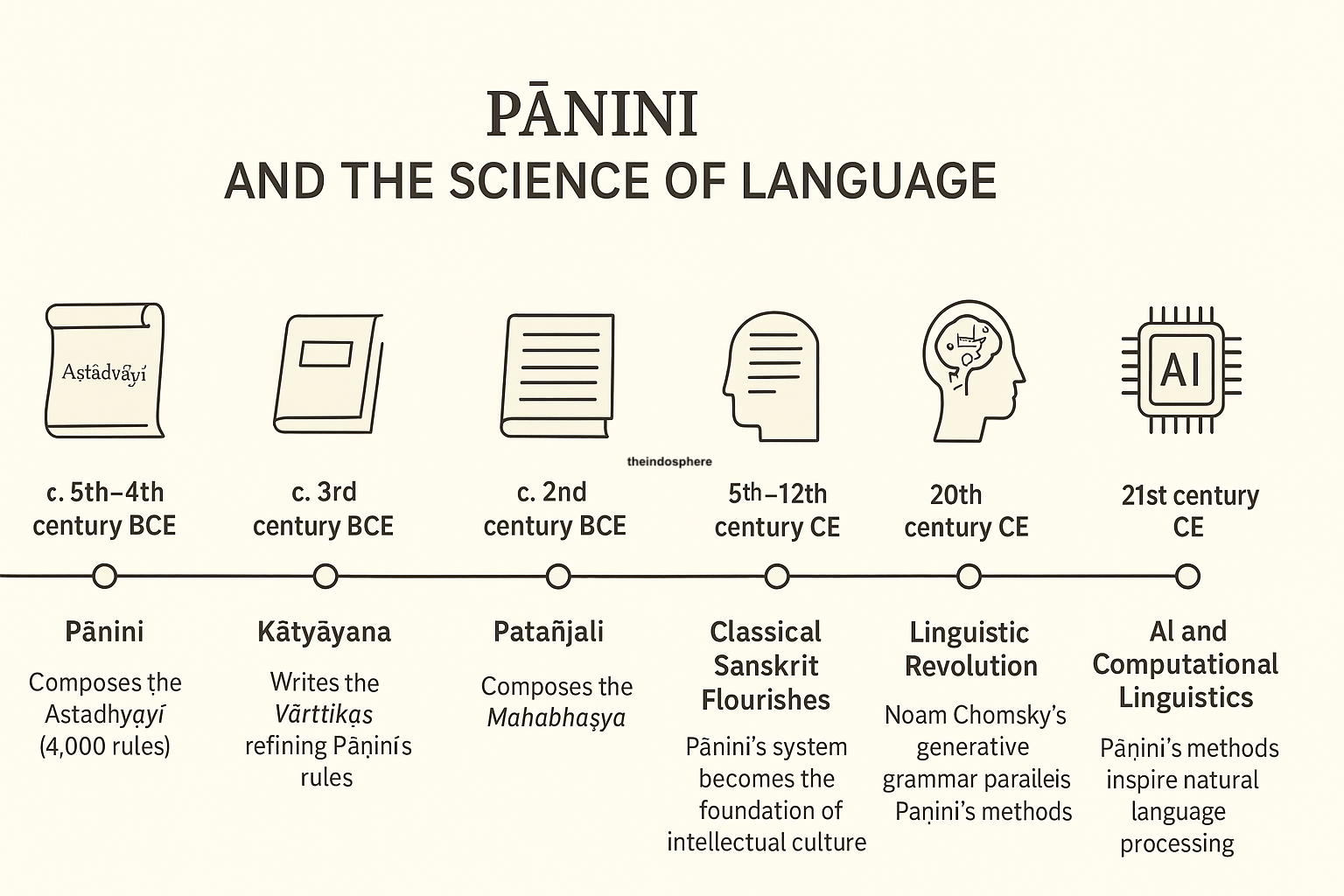

- Katyayana (c. 3rd century BCE): Wrote the Varttikas, short notes clarifying and expanding Panini’s rules.

- Patanjali (c. 2nd century BCE): Composed the Mahabhashya (“Great Commentary”), which cemented Panini’s authority and made grammar (Vyakarana) one of the six Vedangas — disciplines essential for understanding the Vedas.

Together, Panini, Katyayana, and Patanjali formed the foundation of India’s grammatical tradition, a body of work that ensured the precision of Sanskrit across millennia.

Legacy and Influence

Panini’s grammar safeguarded Sanskrit as the language of philosophy, literature, and science. From the Upanishads to Kalidasa’s poetry to the mathematical texts of Aryabhata, all relied on the clarity of expression his system preserved.

But Panini’s impact extended far beyond India:

- In the 18th–19th centuries, European philologists, studying Sanskrit, were astounded by his precision. His grammar became central to the rise of comparative linguistics.

- In the 20th century, Ferdinand de Saussure, often called the father of modern linguistics, had studied Sanskrit grammar and was indirectly shaped by Panini’s ideas.

- Noam Chomsky’s generative grammar bears striking parallels to Panini’s methods, though developed independently.

- Today, Panini’s rule-based system inspires fields like artificial intelligence and computational linguistics, where his sutra method resembles the algorithms that power computers.

Between History and Legend

Much about Panini remains mysterious. His lifetime is reconstructed only from internal evidence in the Ashtadhyayi and later commentaries. Tradition says he met a violent death, mauled by a lion — perhaps a metaphor for the dangers of the wild frontier he lived in.

Yet what survives is greater than any legend: a linguistic edifice that has endured when kingdoms and empires have not.

Why Panini Still Matters

Panini turned spoken sound into science. He showed that language, often thought of as chaotic and fleeting, could be captured in rules as exact as mathematics. His achievement lies not just in shaping Sanskrit, but in proving that language itself has structure — a discovery as profound as any in human thought.

More than two millennia later, when algorithms parse our words and AI learns to mimic human speech, Panini’s work feels startlingly modern. He was not only the grammarian of India, but the first architect of linguistics as a science.

Timeline: Panini and the Science of Language