King of the Gods (Devaraja)

Indra, one of the most ancient and revered deities in Hinduism, is often depicted as the god of lightning, thunder, and rain. He holds a significant place in the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedic scriptures, and is celebrated as the king of the gods (Devaraja). Indra’s mythology is rich with tales of valor, cosmic battles, and the protection of the natural order. This article delves into the origins, attributes, and significance of Indra in Hinduism, exploring his various roles and the evolution of his worship over time.

1. Origins and Early Depictions of Indra

Indra’s earliest mentions are found in the Rigveda, where he is portrayed as the most powerful and prominent god among the deities. The Vedic texts describe Indra as a mighty warrior who rides a celestial chariot, wielding his divine weapon, the Vajra (thunderbolt). He is the son of the sky god Dyaus Pita and the earth goddess Prithvi, symbolizing his dominion over both heaven and earth.

Indra’s physical attributes are often depicted as those of a robust, golden-hued warrior with a fierce and determined expression. His weapon, the Vajra, symbolizes his control over lightning and thunder and his ability to wield these natural forces against his enemies. In addition to the Vajra, Indra is sometimes shown with a bow, a net, and a hook, each representing different aspects of his divine authority.

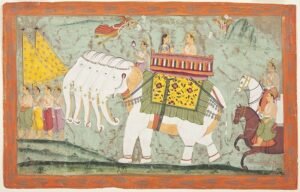

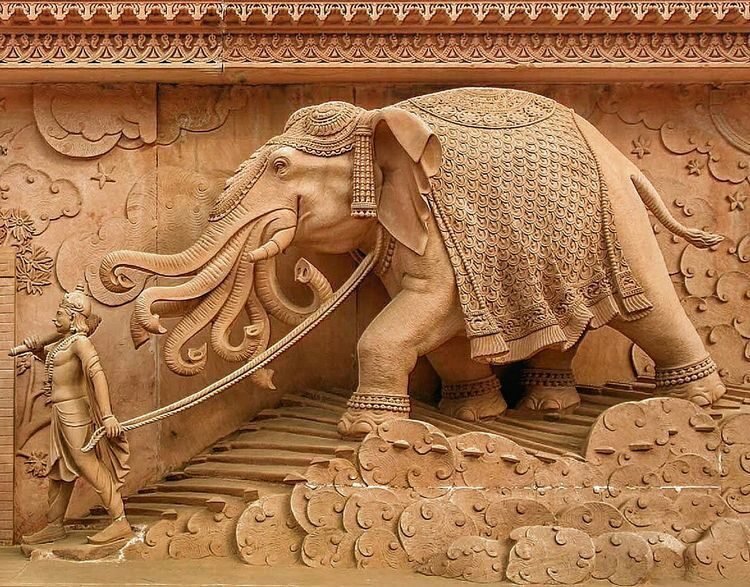

One of the most distinctive features associated with Indra is his mount, the celestial white elephant Airavata. Airavata is no ordinary elephant; he is described in Hindu texts as having four tusks, seven trunks, and a radiant white complexion. Known as the “king of elephants,” Airavata is also referred to by several other names that reflect his divine nature:

- Abhra-Matanga: Meaning “elephant of the clouds,” this name emphasizes Airavata’s association with the heavens and his role in bringing rain, aligning with Indra’s powers over the weather.

- Naga-malla: Translated as “the fighting elephant,” this title highlights Airavata’s strength and prowess, especially in battle.

- Arkasodara: Meaning “brother of the sun,” this name underscores his celestial origin and divine lineage.

Airavata is also the third son of Iravati, and his wife is Abhramu, another divine elephant. Interestingly, in the epic Mahabharata, Airavata is listed as a great serpent, a unique connection that reflects his complex character and perhaps symbolizes his primordial nature and ties to the cosmic forces.

2. Indra’s Role as the King of the Gods

As the king of the gods, Indra holds a central position in the pantheon of Vedic deities. He rules over Svarga, the heaven where the gods reside, and is responsible for maintaining order in the cosmos. Indra’s rule is characterized by his continuous battles against the forces of chaos and darkness, represented by demons (Asuras) and other malevolent beings.

One of the most well-known stories of Indra’s heroism is his battle against the demon Vritra. Vritra had stolen all the waters of the world, causing drought and suffering. Indra, armed with his Vajra and riding Airavata, confronted Vritra in a fierce battle. With the help of the Maruts (storm gods), Indra defeated Vritra, releasing the waters back to the earth and restoring life. This victory earned him the title Vṛtrahant (slayer of Vritra), highlighting his role as the protector of the world.

Indra’s rule is not only about maintaining cosmic order but also about upholding dharma (righteousness). As the leader of the Devas (gods), Indra often presides over assemblies of the gods, making decisions that affect both the divine and earthly realms. His position as Devaraja reflects the Vedic concept of kingship, where the king is seen as the protector and upholder of social and cosmic order.

3. Indra as the God of Rain and Fertility

Indra’s association with rain and thunderstorms makes him an essential deity for agricultural societies, which rely on seasonal rains for their crops. In Hindu mythology, Indra is often invoked during times of drought or insufficient rainfall to bring rain and ensure the fertility of the land. His ability to control the weather also symbolizes his power to nourish and sustain life.

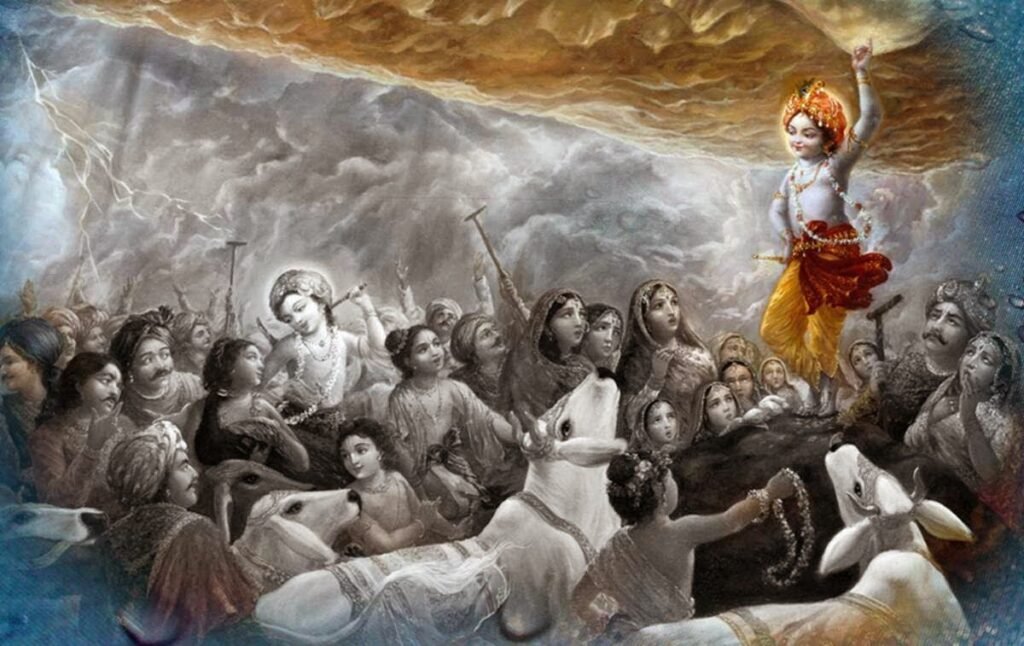

The Krishna Mandap in Mamallapuram, depicts Krishna saving his followers from the Vedic Indra Dev, by lifting the Govardhan mountain.

In Vedic rituals, the worship of Indra often involved the offering of Soma, a sacred plant used to prepare a ritual drink believed to confer immortality. The consumption of Soma by Indra is said to invigorate him, giving him the strength to perform his divine duties. This ritual underscores the belief in Indra’s vital role in maintaining the balance of nature and ensuring prosperity.

The significance of Indra in agricultural societies is further highlighted by his association with festivals and rituals that celebrate the monsoon season. In many parts of India, festivals such as Indra Jatra in Nepal are dedicated to honoring Indra and seeking his blessings for a bountiful harvest. This festival, marked by vibrant processions, mask dances, and the display of Indra’s effigy, is a testament to the enduring reverence for Indra in the region.

4. Indra in Later Hinduism and His Influence Across South Asia

As Hinduism evolved, the prominence of Indra began to wane with the rise of other deities such as Vishnu, Shiva, and Devi. However, Indra remained an important figure in Hindu mythology, particularly in epic literature like the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.

In these later texts, Indra’s character is often portrayed with more complexity, sometimes even highlighting his flaws. For instance, in the Mahabharata, Indra is shown as the father of Arjuna, one of the Pandava princes, whom he aids in the epic battle of Kurukshetra. However, Indra also exhibits human-like traits such as jealousy and insecurity, especially when his position as the king of the gods is threatened by other rising deities.

One of the well-known stories from the Bhagavata Purana is Indra’s confrontation with Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu. When the inhabitants of Vrindavan decide to worship Govardhana Hill instead of offering prayers to Indra, the god becomes furious and sends torrential rains to punish them. However, Krishna lifts the entire hill to protect the villagers, demonstrating that devotion to God is superior to the fear of natural forces.

This story symbolizes the shift in the Hindu religious landscape, where the focus moved from the Vedic gods to the more personal and philosophical aspects of divinity represented by Vishnu and Shiva.

Indra’s influence, however, was not confined to the Indian subcontinent. As Hinduism and Buddhism spread across Asia, Indra’s worship and depiction extended to various regions, including Southeast Asia. In countries like Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia, and Laos, Indra is often revered as a guardian deity and protector of the region.

Cambodia: In Cambodia, Indra is known as the guardian of the eastern direction and is depicted in numerous temples, including the famous Angkor Wat. His image is often shown riding Airavata, symbolizing his power over nature.

Thailand: In Thailand, Indra is known as Phra Indra and is revered in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions. His image can be found in several temples, including Wat Phra Kaew in Bangkok, where he is depicted as a powerful deity with a deep connection to the Thai monarchy.

Indonesia: In Indonesia, particularly in Bali, Indra is worshipped as a rain god and is often invoked in agricultural rituals. The Pura Ulun Danu Bratan temple, dedicated to the goddess of the lake, also honors Indra as a deity of rain and fertility.

Laos: In Laos, Indra is a significant figure in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions. The famous That Luang stupa in Vientiane, a national symbol of Laos, is said to be guarded by Indra, who is depicted in local art and folklore as a protector of the land.

These representations of Indra across South Asia highlight the adaptability of his mythology and his continued relevance in diverse cultural contexts.

5. Traits, Symbolism, and Legacy

Indra’s traits are multifaceted, reflecting the complexities of his character. He is courageous, fierce, and a protector, but he also displays more human characteristics like pride, jealousy, and vulnerability. These qualities make him a relatable figure, embodying the dual nature of gods in Hindu mythology—both divine and fallible.

Indra’s primary weapon, the Vajra, is not only a symbol of his power over lightning but also a representation of spiritual fortitude and resilience. The Vajra is often depicted as a scepter-like object with prongs that symbolize the ability to break through ignorance and evil. In Buddhist iconography, the Vajra is also an important symbol, representing the indestructible nature of truth and the firmness of the mind.

The celestial elephant Airavata is another significant aspect of Indra’s symbolism. Airavata, often depicted as white with four tusks and seven trunks, represents purity, strength, and the ability to bring rain, which is essential for life. The image of Indra riding Airavata is a powerful metaphor for his control over the elements and his role as a sustainer of life.

Despite the decline in his worship in later Hindu traditions, Indra’s legacy persists in various forms. He is still invoked in certain rituals and festivals, especially those related to rain and agriculture. His stories continue to be retold in classical literature, temple art, and folklore, reminding people of his once-preeminent status in the divine hierarchy.

Indra’s influence also extends beyond religious worship. In various South Asian languages, terms related to Indra are used metaphorically to denote strength, leadership, and control. For example, the word “Indrajaal” refers to a magical or illusionary net, often symbolizing the complex and sometimes deceptive nature of power.