Origins of Martial Arts

When examining the origins of martial arts, most people think of East Asia, where styles like Kung Fu and Karate have become global icons. Yet long before these traditions arose, India had already developed martial systems deeply rooted in spiritual discipline, combat strategy, and holistic personal development. Indian martial arts are far more than techniques of physical combat; they embody a synthesis of bodily mastery, philosophical depth, cultural heritage, and ancient medical knowledge.

Tracing the origins of martial arts in India reveals an ancient evolution – from prehistoric tribal warfare and Vedic battle rituals to temple guardians and warrior-monks. Over centuries, these martial systems spread beyond the subcontinent, influencing combat traditions across Southeast Asia and East Asia. Their resilience, adaptability, and profound philosophy make Indian martial arts an enduring subject of interest in martial history and cultural anthropology.

Prehistoric and Vedic Beginnings

The genesis of martial practices in India goes as far back as the Stone Age, where rudimentary forms of defense and hunting laid the foundation for more organized systems of combat. Cave paintings in Bhimbetka and archaeological remains across the subcontinent indicate a society that revered physical prowess.

With the advent of the Vedic period (circa 1500 BCE), martial skills were increasingly codified. The Vedas, especially the Rigveda and Atharvaveda, are rich in references to warrior deities like Indra and Rudra, battle hymns, and invocations for strength and victory. The science of warfare became formalized in the Dhanurveda, considered one of the four Upavedas, which detailed not only archery but the use of various weapons, military formations, and combat etiquette.

Training was a lifelong duty for the Kshatriya class. Rigorous regimens included weapon handling, wrestling (mallayuddha), horse and elephant riding, chariot racing, and physical conditioning. Martial education was inseparable from religious and ethical instruction, aimed at developing a dharmic warrior who fought not out of aggression but responsibility.

Martial Ethics and Training in the Epics

The epics Mahabharata and Ramayana serve as encyclopedias of Indian martial wisdom. These narratives are replete with episodes that explore not just the art of warfare, but its moral and philosophical underpinnings.

Warriors such as Arjuna, Bhima, Karna, and Hanuman exemplify the ideal martial character—brave, skilled, loyal, yet reflective of higher values like truth, restraint, and righteousness. Concepts such as dharma yuddha (just war), niyuddha (duel combat), and adharma (unjust conduct) are thoroughly explored.

Weapons training was rigorous and diverse: the gada (mace), chakra (discus), khadga (sword), parashu (axe), bhuja (arm blades), and dhanush (bow) all featured prominently. Martial education occurred in gurukuls or ashrams, where disciples trained under a guru, who was not just an instructor but a spiritual guide. Training included not just combat but meditation, mantra chanting, and scriptural study, embodying a holistic approach.

Martial Systems in the Classical Age and Sangam Period

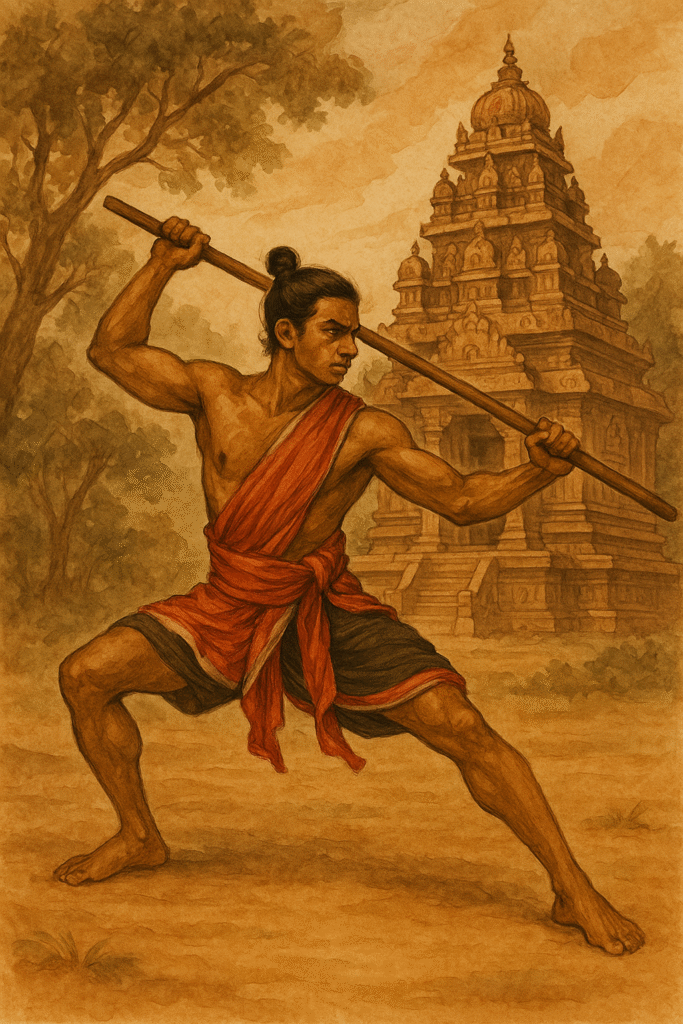

The Sangam period (circa 300 BCE to 300 CE) marked the flourishing of martial traditions in South India. Tamil literature like the Purananuru and Silappatikaram provide insights into the highly militarized culture of the time. Warrior clans practiced martial arts as both sport and survival craft, with arts like Silambam and Kuttu Varisai taking center stage.

- Silambam: Primarily a weapon-based martial art, Silambam utilizes bamboo sticks, swords, shields, and flexible weapons. The art is rhythm-based, combining swift footwork, circular motions, and rapid strikes. It was taught in ancient martial schools and was a prerequisite for royal guards and soldiers.

- Kalaripayattu: Hailing from Kerala, Kalaripayattu is regarded by many scholars as the oldest living martial art in the world. It encompasses meipayattu (physical training), kolthari (wooden weapons), ankathari (metal weapons), and verma kalai (vital point attacks). Kalari masters were also healers, trained in Ayurveda, using herbal medicine and massage therapies to treat injuries. The spiritual foundation of Kalaripayattu included prayers to deities like Bhagavati and rituals invoking divine protection.

Buddhism and the Martial Transmission to East Asia

During the reigns of the Mauryan and Gupta empires, martial systems were further institutionalized. Military academies flourished under state patronage. Concurrently, the spread of Buddhism carried Indian martial ideas across the Himalayas into China and beyond.

One of the most legendary figures in this transmission is Bodhidharma, a monk from the Tamil region who journeyed to China in the 6th century CE. At the Shaolin Temple, he is said to have introduced a regimen of breathing techniques, postures, and movement forms to strengthen the monks for long hours of meditation. These exercises formed the foundation of what would later evolve into Shaolin Kung Fu.

Bodhidharma’s teachings were rooted in Indian yogic and martial systems, including elements of Kalaripayattu and Vajramushti, thereby linking the Chinese and Indian martial lineages.

Regional Martial Traditions Across India

India’s cultural diversity gave rise to a rich tapestry of regional martial systems:

- Thang-Ta (Manipur): A martial art combining sword, spear, and unarmed combat, deeply tied to Meitei spiritual practices and rituals. It is both a battlefield technique and a sacred dance form.

- Gatka (Punjab): Developed by the Sikh Khalsa, Gatka emphasizes swordplay, footwork, and spiritual discipline. Practiced with wooden sticks and real weapons, it was designed to defend righteousness (dharma) and protect the weak.

- Mardani Khel (Maharashtra): Originating in the Maratha warrior tradition, this art includes the use of the patta, bhala (spear), and lathi (stick), and is characterized by mobile combat and horseback fighting.

- Musti Yuddha (North India): An ancient form of unarmed combat similar to boxing, it focuses on powerful punches, grapples, and knee strikes. It was practiced by wrestlers and royal guards.

- Varma Kalai (Tamil Nadu): A unique system based on marmam (vital points), Varma Kalai is both a healing art and a lethal fighting style. Its knowledge was traditionally restricted to select warrior families and temple guardians.

Philosophical and Healing Dimensions

What sets Indian martial arts apart is their deeply philosophical and spiritual orientation. They are grounded in the concept of sadhana—a disciplined path toward self-realization.

Key features include:

- Ethical codes of conduct (yama and niyama)

- Pranayama (breathing control) to regulate energy flow

- Awareness of chakras and nadis, subtle energy channels

- Integration with Ayurvedic healing, including diet, massage, and herbal treatments

Many martial traditions regarded the body as a sacred temple, to be perfected not just for battle but for enlightenment. Masters often trained in yoga, mantra recitation, and tantra, blending physical power with metaphysical insight.

Colonial Suppression and Cultural Revival

Indian martial arts underwent a prolonged decline during the era of foreign invasions and colonization:

- Islamic conquests led to the destruction or absorption of temple-based martial schools.

- British rule banned or discouraged martial practices like Kalaripayattu and Silambam, viewing them as sources of rebellion. Schools were closed, and practitioners faced persecution.

Despite this, many arts went underground or survived in rural communities. Stories, songs, and rituals preserved these traditions. In the 20th century, especially post-independence, there was a significant cultural revival:

- State-sponsored training centers and academies were established.

- Martial arts began to appear in Indian cinema, sparking public interest.

- Cultural festivals and international exchange programs promoted traditional arts.

- Some systems were adapted into modern self-defense programs and sports curricula.

Global Influence and Contemporary Relevance

India’s martial arts have left a global imprint. Through centuries of migration, pilgrimage, and trade, Indian martial knowledge influenced:

- Southeast Asian combat systems like Silat (Indonesia/Malaysia), Krabi-Krabong (Thailand), and Bando (Myanmar)

- Chinese martial arts, especially Shaolin traditions

- Modern yoga and wellness, particularly through practices like Surya Namaskar, pranayama, and mind-body integration

Today, Indian martial arts are experiencing a renaissance, not only as heritage arts but as tools for physical fitness, self-defense, mental clarity, and cultural identity. International enthusiasts are now training in Kalaripayattu, Silambam, and other native arts, drawn by their depth and holistic approach.

The story of Indian martial arts is one of endurance, adaptability, and profound wisdom. From ancient battlefields to monastic halls, from rural arenas to global stages, these traditions continue to evolve while preserving their spiritual core.

They are more than systems of combat—they are ways of life, grounded in dharma, discipline, and self-mastery. In a world rediscovering ancient paths to balance and wellness, the martial arts of India offer timeless guidance, strength, and inspiration.