Few words from India have traveled as far and wide as Yoga. Today, it conjures images of mats and postures in gyms and studios across the world. But in its origins, Yoga was never just physical exercise. It was a discipline of body, mind, and spirit, rooted in ancient Indian cosmology and philosophy, evolving over millennia from ritual practice to a comprehensive way of life.

Vedic and Pre-Vedic Roots

The earliest hints of Yogic ideas can be traced to the Rigveda (c. 1500–1200 BCE). The term yuj — meaning “to yoke” or “to unite” — appears in contexts of harnessing horses, but symbolically it referred to uniting human will with cosmic order (ṛta). Vedic seers practiced breath control (prāṇa), ascetic discipline, and meditation as means of deepening ritual insight.

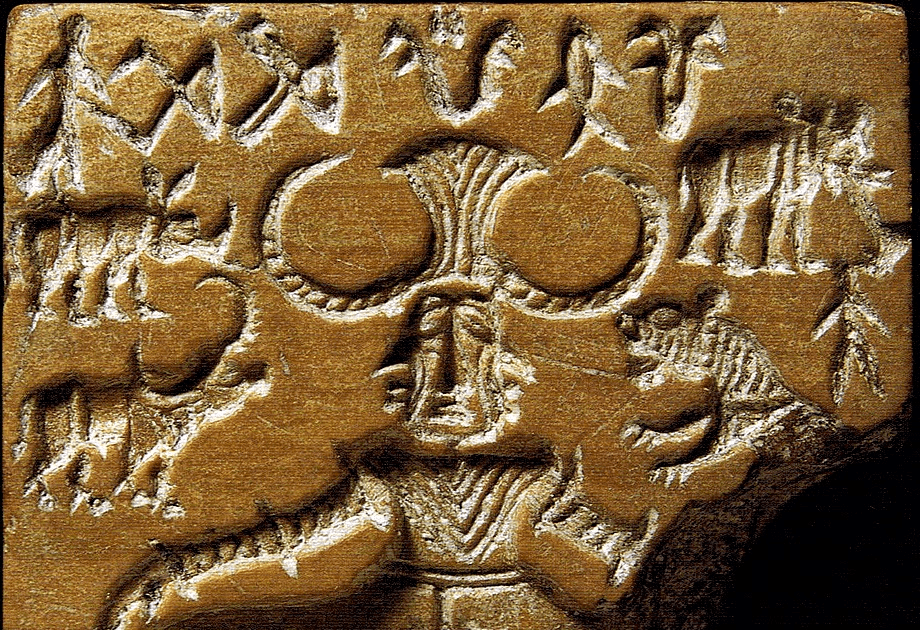

Archaeological finds from the Indus Valley Civilization — such as the famous “Pashupati seal” depicting a horned figure in a cross-legged pose — suggest that proto-Yogic postures and cultic meditation may have been practiced long before the Vedas were codified.

Upanishadic Vision

By the Upanishadic period (c. 800–500 BCE), Yoga matured into a path of self-realization. Texts like the Katha Upanishad describe the body as a chariot, the senses as horses, and the mind as reins — an allegory for Yogic control of inner faculties. The Śvetāśvatara Upanishad outlines meditation on the supreme reality, breath regulation, and concentration.

Here, Yoga was less about posture and more about inner stillness, a process of moving from multiplicity to union with Brahman.

The Bhagavad Gītā: Paths of Yoga

The Bhagavad Gītā (c. 2nd century BCE) gave Yoga its plural forms. Krishna outlines three main Yogas:

- Karma Yoga — the Yoga of action, selfless duty without attachment to results.

- Jñāna Yoga — the Yoga of knowledge, realizing the self’s unity with the eternal.

- Bhakti Yoga — the Yoga of devotion, surrender to the divine.

This synthesis made Yoga a universal discipline, adaptable to one’s temperament. The Gītā ensured that Yoga was not the preserve of renunciants alone but could be lived amidst daily life.

Patañjali and Classical Yoga

Around the 2nd century BCE – Patañjali systematized Yoga in the Yoga Sūtras, a text that remains foundational. He defined Yoga as:

Yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ — Yoga is the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind.

Patañjali outlined the eightfold path (aṣṭāṅga yoga):

- Yama (ethical restraints)

- Niyama (discipline)

- Āsana (posture)

- Prāṇāyāma (breath control)

- Pratyāhāra (withdrawal of senses)

- Dhāraṇā (concentration)

- Dhyāna (meditation)

- Samādhi (absorption)

This Rāja Yoga stressed discipline of mind and spirit. Physical postures were only one part, and not the central one.

Buddhist and Jain Yogas

Parallel to Hindu traditions, Buddhism and Jainism developed their own Yogic systems.

- Early Buddhism emphasized meditation (dhyāna/jhāna) for achieving Nirvāṇa. Yogic practices of mindfulness, breath awareness, and insight (vipassanā) became central.

- Jains pursued ascetic Yogas of non-attachment and self-discipline, aiming at liberation of the soul from karmic bondage.

Thus, Yoga became a shared spiritual technology across India’s religious spectrum.

Tantra and Haṭha Yoga

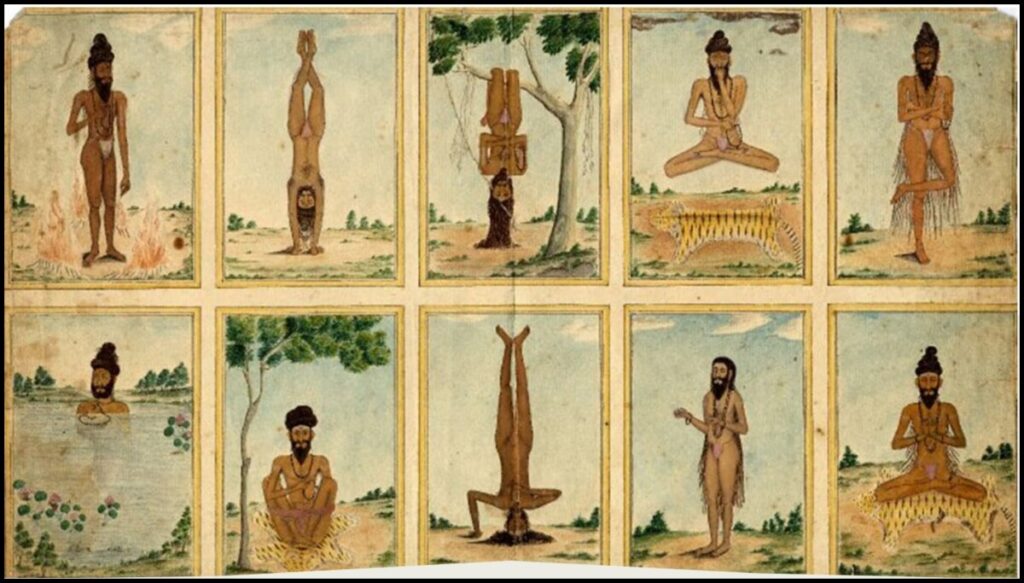

From the 9th–12th centuries CE, Tantric and Haṭha Yoga reshaped the tradition. Texts like the Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā (15th c.) emphasized physical postures, breath techniques, and awakening of kuṇḍalinī energy through the body’s subtle channels (nāḍīs and cakras).

This was the birth of Yoga as a bodily discipline — still deeply spiritual, but now giving greater prominence to āsanas and prāṇāyāma.

Yoga in the Modern World

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Yoga was reimagined for a global audience. Swami Vivekananda presented Yoga as a universal spiritual science at the Parliament of Religions in Chicago (1893). Later, teachers like T. Krishnamacharya, B.K.S. Iyengar, and Pattabhi Jois popularized āsana-based Yoga systems, focusing on health, flexibility, and well-being.

By the 20th century, Yoga had become a global phenomenon, often stripped of its metaphysical roots and practiced as a secular discipline. Yet in India, it continued as both sādhanā (spiritual practice) and śikṣā (discipline of health and mind).

In 2014, the United Nations declared June 21st as International Day of Yoga, marking its recognition as a shared human heritage.

Legacy

Across three millennia, Yoga has transformed from Vedic ritual discipline to Upanishadic meditation, from Patañjali’s system to Tantric Haṭha practices, from sacred devotion to global wellness culture.

At its core, however, the idea remains constant: union — of breath and body, mind and self, self and the eternal. Yoga continues to bridge the inner and outer worlds, a practice as ancient as the Ṛgveda and as modern as the present moment.