The Mauryan Empire, established by Chandragupta Maurya in 321 BCE, marked a significant period in ancient Indian history, becoming one of the largest empires of its time. The empire reached its zenith under Ashoka the Great, a ruler whose legacy has been both celebrated and critically reexamined.

Traditionally portrayed as a remorseful conqueror who embraced Buddhism following the devastating Kalinga War, Ashoka is credited with spreading Buddhism across Asia and promoting a policy of non-violence and ethical governance. However, recent scholarship challenges this narrative, suggesting that Ashoka’s adoption of Buddhism occurred before the Kalinga War and may have been motivated by political strategy as much as personal transformation. This article delves into the complexities of Ashoka’s reign, examining his rise to power, the Kalinga War, his promotion of Buddhism, and the lasting impact of his legacy on both Indian and global history.

The Rise of the Mauryan Empire

A. Foundation by Chandragupta Maurya

The Mauryan Empire was founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 321 BCE, following his successful overthrow of the Nanda dynasty with the assistance of his advisor Chanakya, also known as Kautilya. This alliance between Chandragupta and Chanakya was instrumental in the establishment and consolidation of Mauryan power. Chanakya’s treatise, the Arthashastra, provided a comprehensive guide to statecraft, economics, and military strategy, and it laid the intellectual foundation for the administration of the vast empire.

Chandragupta’s rule was characterized by the expansion of the empire across northern India and into parts of Central Asia, a feat accomplished through both military conquest and diplomatic alliances. He established a centralized administrative structure that was unprecedented in its complexity and efficiency, featuring a network of spies, a standing army, and a bureaucracy that managed everything from taxation to infrastructure. The capital, Pataliputra (modern-day Patna), became a hub of political, economic, and cultural activity.

B. Expansion under Bindusara

Following Chandragupta’s abdication and retreat to a Jain monastery, his son Bindusara ascended to the throne around 297 BCE. Bindusara, known as “Amitraghata” (Slayer of Enemies), continued his father’s expansionist policies, extending the empire further into the southern regions of the Indian subcontinent. While Bindusara’s reign is less documented than those of Chandragupta or Ashoka, it was nonetheless a period of consolidation and expansion that helped solidify the Mauryan Empire’s dominance over a vast and diverse territory.

Bindusara maintained the administrative structures established by Chandragupta and continued to build on the political and economic foundations of the empire. His reign set the stage for Ashoka’s eventual rise to power, ensuring that the empire was both expansive and stable when Ashoka took the throne.

Ashoka’s Early Reign and the Kalinga War

A. Ascension to the Throne

Ashoka’s rise to power was marked by political intrigue and violence. Following Bindusara’s death, a succession struggle ensued, with Ashoka reportedly eliminating several of his brothers to secure his position as emperor. By 268 BCE, Ashoka had established himself as the unchallenged ruler of the Mauryan Empire, though his reputation during these early years was one of ruthlessness and ambition.

Once in power, Ashoka continued his predecessors’ policies of expansion, focusing on consolidating the empire’s control over newly acquired territories. His military campaigns were both extensive and brutal, aimed at securing the empire’s borders and subduing rebellious regions. This period of Ashoka’s reign was characterized by a focus on power and conquest, earning him the nickname “Chandashoka” (Ashoka the Cruel) among his contemporaries.

B. The Kalinga War

The Kalinga War, fought in 261 BCE, is often cited as the turning point in Ashoka’s life and reign. Kalinga, located on the eastern coast of India in what is now Odisha, was one of the few remaining independent regions resisting Mauryan control. The war was catastrophic, with ancient sources claiming that over 100,000 soldiers and civilians were killed, and many more were displaced.

While traditional accounts suggest that the horror of the war led Ashoka to embrace Buddhism, recent research indicates that Ashoka had already been a practicing Buddhist for several years prior to the conflict. The decision to invade Kalinga was likely motivated by strategic considerations, as controlling the region would have allowed the Mauryan Empire to secure important trade routes and consolidate its control over the eastern seaboard.

The aftermath of the war did lead to a shift in Ashoka’s policies, but rather than a sudden conversion, it appears to have been a reinforcement of his existing beliefs. Ashoka’s inscriptions suggest that he was deeply affected by the suffering caused by the war, which may have prompted him to more actively promote the principles of Dhamma (Dharma), which emphasized non-violence, compassion, and moral governance.

C. Ashoka’s Transformation

The transformation of Ashoka from a conqueror to a proponent of non-violence and ethical rule is a complex narrative that cannot be reduced to a single event. Ashoka’s adoption of Buddhism was likely influenced by multiple factors, including personal belief, political expediency, and the need to legitimize his rule in a diverse and vast empire.

Ashoka’s promotion of Dhamma was as much a political tool as it was a moral stance. By advocating for a code of ethics that transcended religious boundaries, Ashoka sought to unify his subjects under a common moral framework, thereby strengthening the cohesion of his empire. This strategy also helped to mitigate the resentment and unrest that often followed his military campaigns, particularly in regions like Kalinga that had suffered greatly under Mauryan conquest.

The Spread of Buddhism

A. Ashoka’s Role in Promoting Buddhism

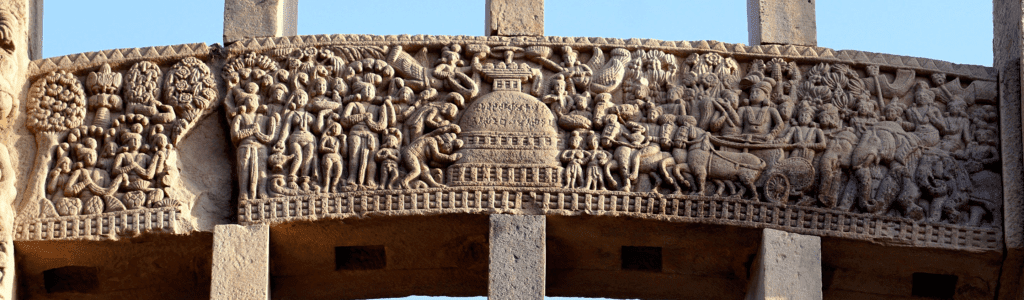

Ashoka’s reign marked a significant period in the spread of Buddhism both within India and beyond its borders. As a ruler, Ashoka provided extensive patronage to the Buddhist monastic community, building stupas and viharas, and offering material support to monks and scholars. His reign saw the construction of some of the most important Buddhist monuments in India, many of which became centers of pilgrimage and learning.

One of Ashoka’s most significant contributions to Buddhism was his role in convening the Third Buddhist Council around 250 BCE in Pataliputra. The council was held to address doctrinal disputes and to purify the Sangha (monastic community) by expelling monks who were considered heretical or corrupt. This council played a crucial role in preserving and propagating the Buddhist teachings, ensuring their survival and dissemination for future generations.

Ashoka also promoted the translation of Buddhist texts into local languages, making the teachings more accessible to the general population. This initiative helped to spread Buddhism beyond the elite circles of scholars and monks, allowing it to take root among the common people across the empire.

B. Ashoka’s Edicts

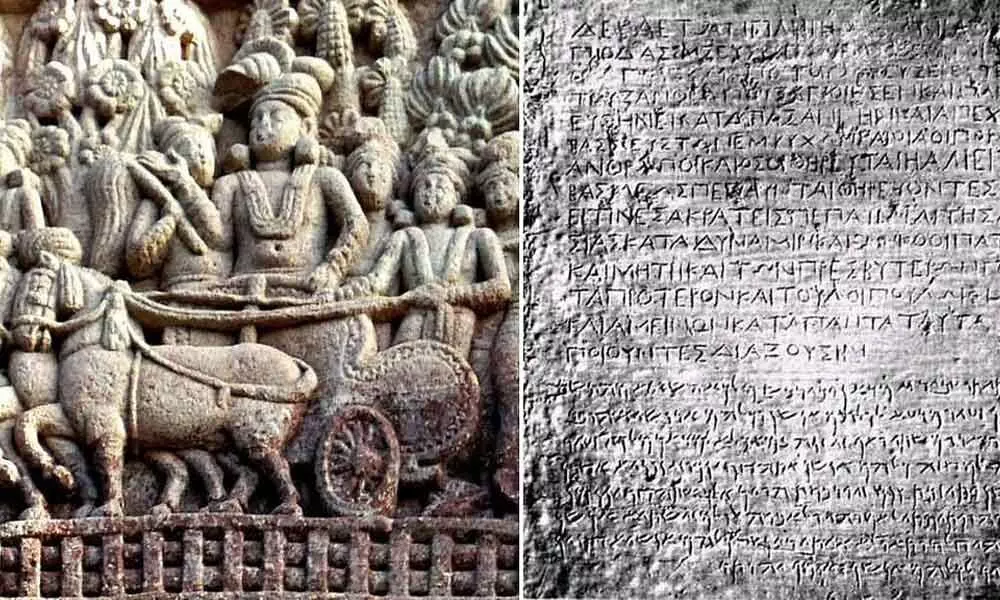

The Ashokan Edicts are among the most important sources of information about his reign and policies. These inscriptions, found on rocks, pillars, and cave walls across the Indian subcontinent, provide a detailed account of Ashoka’s principles of governance and his commitment to Dhamma.

The edicts are written in various languages, including Prakrit, Greek, and Aramaic, reflecting the linguistic diversity of the Mauryan Empire. They cover a wide range of topics, from the importance of ethical conduct and religious tolerance to the welfare of animals and the administration of justice. The edicts also reveal Ashoka’s efforts to promote non-violence (ahimsa), compassion, and truthfulness among his subjects.

The Major Rock Edicts, for instance, emphasize the moral duties of individuals, including respect for parents, elders, and teachers, as well as the importance of treating all living beings with kindness. The Pillar Edicts, often adorned with intricate carvings and topped with animal capitals, further reinforce these messages, highlighting Ashoka’s desire to govern his empire through moral persuasion rather than force.

However, the edicts also served as a tool of political propaganda. By inscribing his principles on rocks and pillars across the empire, Ashoka was able to project his authority and promote his image as a just and benevolent ruler. The edicts helped to legitimize his rule, particularly in regions that had been recently conquered or were culturally distinct from the Mauryan heartland.

C. Missionary Efforts and International Influence

Ashoka’s efforts to spread Buddhism were not confined to the Indian subcontinent. He sent missionaries to various regions, including Sri Lanka, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia, with the aim of sharing the teachings of the Buddha with other cultures. These missionary efforts were instrumental in establishing Buddhism as a major world religion.

One of the most successful of these missions was led by Ashoka’s son, Mahinda, who traveled to Sri Lanka around 250 BCE. Mahinda’s efforts led to the conversion of the Sri Lankan king, Devanampiya Tissa, to Buddhism, and the subsequent establishment of Buddhism as the dominant religion on the island. This mission laid the foundation for the long-standing Buddhist tradition in Sri Lanka, which continues to be a major center of Theravada Buddhism today.

In addition to Sri Lanka, Ashoka’s missionary efforts extended to regions as far-flung as Central Asia and the Hellenistic kingdoms. These interactions facilitated a rich cultural exchange, and it is believed that Ashoka’s envoys played a role in the development of Greco-Buddhist art, particularly in the Gandhara region, which fused classical Greek artistic techniques with Buddhist iconography. The spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road helped establish it in China, Korea, and Japan, where it evolved into new schools of thought, such as Mahayana Buddhism.

Ashoka’s contributions to the spread of Buddhism were monumental, but it’s important to recognize the broader geopolitical context in which these efforts occurred. The spread of Buddhism was not merely a religious mission but also a diplomatic strategy to establish cultural ties with other powerful states, thereby securing Ashoka’s legacy and influence beyond India. His missions to Southeast Asia, in particular, helped to integrate these regions into a broader Buddhist cultural sphere that persisted long after the fall of the Mauryan Empire.

Ashoka’s Legacy

A. Governance and Social Reforms

Ashoka’s legacy is deeply intertwined with his innovative approach to governance. After the Kalinga War, he sought to implement a model of rulership that blended the traditional duties of a king with Buddhist ethical principles. His commitment to non-violence (ahimsa) and the welfare of all beings became central to his administrative policies. He established a network of “Dhamma Mahamatras” (officers of righteousness) who were tasked with spreading the principles of Dhamma, overseeing social welfare programs, and ensuring justice throughout the empire.

Ashoka’s social reforms were extensive. He promoted public health by building hospitals, both for humans and animals, and he invested in infrastructure projects such as roads, wells, and rest houses, which facilitated trade and communication across the vast empire. His policies emphasized environmental conservation, the humane treatment of animals, and the importance of maintaining public order through moral example rather than coercion.

Moreover, Ashoka’s approach to governance was inclusive and forward-thinking. He encouraged religious tolerance and sought to foster a sense of unity among his subjects, who were diverse in their cultural, linguistic, and religious practices. While Buddhism was the religion closest to his heart, Ashoka’s edicts reflect a deep respect for all religious traditions, and he urged his subjects to practice their faiths with sincerity and mutual respect.

B. Long-term Impact and Historiographical Reevaluation

Ashoka’s reign has been the subject of extensive historical debate. For centuries, he was celebrated as a model ruler, whose reign was marked by peace, prosperity, and the spread of Buddhism. This image was largely shaped by later Buddhist chronicles, which portrayed Ashoka as an ideal king who had been transformed by his embrace of the Buddha’s teachings.

However, modern historiography has begun to reevaluate this image. Some scholars argue that the portrayal of Ashoka as a remorseful pacifist may be an oversimplification, influenced by religious narratives that sought to emphasize his role in the promotion of Buddhism. The discovery of Ashoka’s edicts, particularly those that discuss the use of force against religious dissenters and his continued emphasis on military preparedness, suggest that Ashoka’s reign was more complex than the traditional accounts indicate.

Recent research also highlights the political motivations behind Ashoka’s promotion of Buddhism. As the ruler of a vast and culturally diverse empire, Ashoka may have seen Buddhism as a unifying ideology that could help solidify his authority and legitimize his rule. His emphasis on Dhamma, while rooted in Buddhist ethics, was broad enough to appeal to people of various faiths, thereby promoting social cohesion and reducing the likelihood of rebellion.

Ashoka’s long-term impact on Indian and global history is undeniable. His promotion of Buddhism helped to establish it as a major world religion, and his policies of non-violence and social welfare have been admired by leaders and scholars throughout history. The symbol of the Ashokan lion capital was adopted as the national emblem of India, and his message of tolerance and ethical governance continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about leadership and morality.

Ashoka the Great remains one of the most complex and intriguing figures in world history. His reign, marked by both conquest and compassion, has left an indelible legacy on the cultural and religious landscape of Asia. While traditional accounts emphasize his transformation into a benevolent ruler following the Kalinga War, modern scholarship presents a more nuanced picture of a king who skillfully balanced personal belief with political pragmatism.

Ashoka’s contributions to the spread of Buddhism and his innovative approach to governance have ensured his place in history as a visionary leader. However, the reevaluation of his legacy also reminds us of the complexities of historical interpretation and the need to consider multiple perspectives when assessing the impact of historical figures.

In today’s world, Ashoka’s message of tolerance, non-violence, and ethical leadership is more relevant than ever. As we reflect on his life and reign, we are reminded of the enduring power of compassion and the importance of leadership that prioritizes the welfare of all.