Introduction

Before the emergence of the Mughal Empire in the early 16th century, the Indian subcontinent was a patchwork of regional kingdoms, with the Delhi Sultanate as the predominant power in the north. The period was characterized by political fragmentation, cultural diversity, and a lack of centralized control. The arrival of the Mughals, who traced their lineage to both Genghis Khan and Timur, marked the beginning of a new era. Their empire not only unified a vast territory but also left an indelible mark on Indian culture, architecture, and society.

The Mughal Empire is often remembered for its magnificent contributions to art and architecture, but it was also a period of significant military conquests, complex political strategies, and intricate administrative systems. However, beneath this outward splendour lies a darker side, one marred by religious persecution, cruelty, and subjugation. This article delves into the rise and fall of this remarkable empire, exploring its impact on the Indian subcontinent and its enduring legacy; as well as the grim atrocities that stained its legacy.

I. The Rise of the Mughal Empire:

Babur’s Early Life and Ambitions

Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, was born in 1483 in present-day Uzbekistan, into the Timurid dynasty. As a descendant of Timur on his father’s side and Genghis Khan on his mother’s, Babur inherited both ambition and the legitimacy to rule. His early life was marked by constant struggle to retain his ancestral seat in Central Asia. After several failed attempts to establish a stronghold in Samarkand, Babur turned his attention towards India, a land rich in resources and political fragmentation.

The political landscape of northern India in the early 16th century was ripe for conquest. The Delhi Sultanate, which had dominated the region for centuries, was in decline, weakened by internal strife and external threats. Babur, seizing this opportunity, led his forces into India. His ambitions were not merely to raid but to establish a lasting empire. This was evident in his meticulous planning and strategic alliances with local chieftains who were disillusioned with the Lodi dynasty.

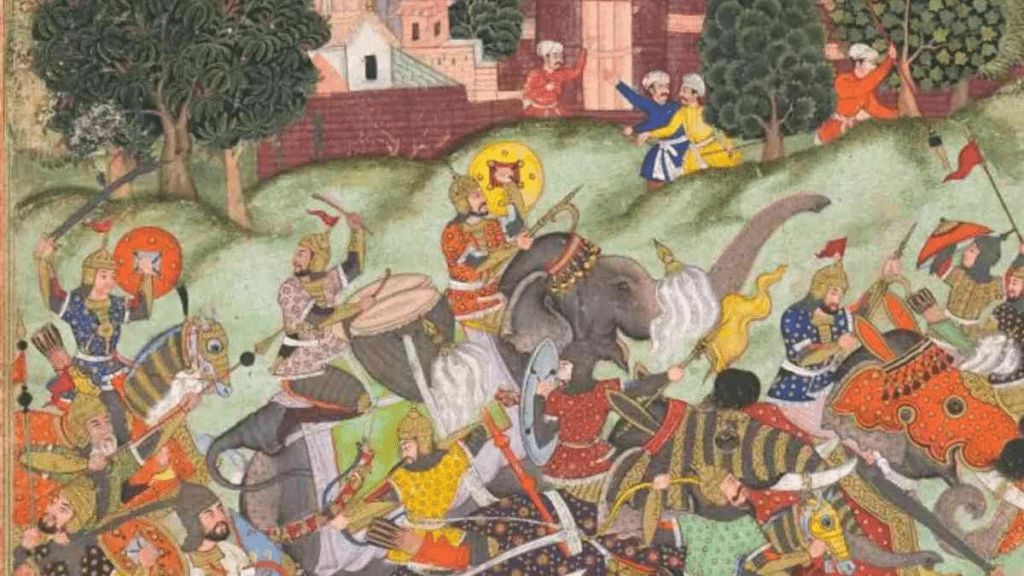

The Battle of Panipat

In 1526, Babur’s forces met the army of Ibrahim Lodi, the last Sultan of Delhi, at the Battle of Panipat. This battle is one of the most significant in Indian history, marking the end of the Delhi Sultanate and the beginning of Mughal dominance in India. Babur’s army, though smaller, was highly disciplined and made innovative use of artillery, a military technology relatively new to the subcontinent. The battle was a decisive victory for Babur, who killed Ibrahim Lodi and seized control of Delhi.

The victory at Panipat was not merely a military triumph but also a psychological one. It established Babur as a formidable power in India and laid the foundation for the Mughal Empire. Babur, unlike previous invaders, had a vision of establishing a permanent empire rather than just plundering the land. He took steps to stabilize the region, extending his control over the rich northern plains and integrating local rulers into his administration.

Formation of the Empire

Following his victory at Panipat, Babur faced the daunting task of consolidating his newly acquired territories. India, with its vast and diverse population, presented a unique challenge. Babur employed a combination of military might and diplomatic acumen to bring various regions under his control. He respected local customs and sought to integrate local elites into his administration, ensuring their loyalty to the new Mughal regime.

Babur’s memoirs, the Baburnama, provide insight into his ambitions and governance style. He was not just a conqueror but also a statesman who understood the complexities of ruling a diverse and vast empire. His policies laid the groundwork for the administrative and cultural policies that his successors would further develop, leading to the establishment of one of the most powerful empires in the Indian subcontinent.

II. Mughal Emperors and Their Reigns

Humayun

Humayun, Babur’s son, inherited the Mughal Empire in 1530. However, his reign was fraught with challenges, primarily due to the ambitious regional powers and his lack of military acumen compared to his father. Humayun faced constant threats from Sher Shah Suri, an Afghan noble who managed to defeat him and take over the empire temporarily. Humayun spent several years in exile, wandering through Persia, which influenced his taste for Persian culture, a hallmark of later Mughal aesthetics.

Despite his early setbacks, Humayun’s persistence paid off when he regained the throne in 1555 with the help of Persian allies. However, his second tenure was short-lived; he died in 1556 after a tragic fall from the steps of his library. Humayun’s reign, though unstable, was crucial in keeping the Mughal legacy alive. His son, Akbar, inherited a fragile empire but would go on to transform it into one of the most stable and prosperous empires in history.

Akbar

Akbar, often considered the greatest Mughal emperor, ascended the throne at the tender age of 13. His early reign was dominated by regents, but by the time he took control, Akbar had developed into a shrewd leader with an inclusive vision for his empire. He expanded the Mughal Empire significantly, bringing vast regions of northern and central India under his control. Akbar’s military conquests were complemented by his diplomatic marriages to Rajput princesses, which helped secure alliances with powerful Hindu states.

One of Akbar’s most significant contributions was his administrative reforms. He established an efficient bureaucracy that centralized control while respecting the autonomy of local rulers. Akbar also implemented a fair revenue system based on agricultural productivity, which ensured the empire’s financial stability.

Religiously, Akbar is known for his policy of Sulh-i-Kul, or “universal tolerance.” He engaged in dialogues with scholars of different faiths and even attempted to create a syncretic religion, Din-i Ilahi, which blended elements of various religions. Although Din-i Ilahi did not survive beyond his reign, Akbar’s approach to governance fostered a sense of unity in a diverse empire.

Jahangir

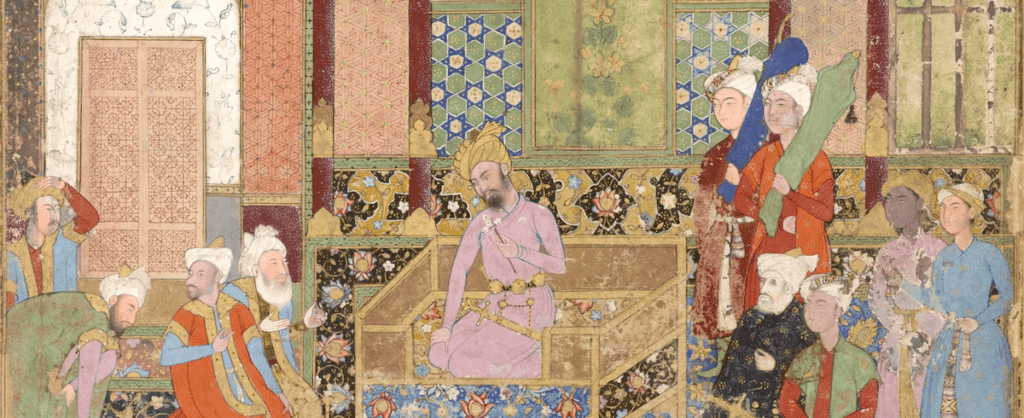

Jahangir, Akbar’s son, inherited a stable and prosperous empire. Known for his love of the arts, Jahangir’s reign saw the flourishing of Mughal painting and architecture. He continued his father’s policies of religious tolerance and patronized artists, poets, and scholars. His court became a center of cultural activity, with Persian influence particularly strong.

Jahangir’s reign, however, was also marked by the increasing influence of his wife, Nur Jahan, who effectively became the power behind the throne. Nur Jahan was an astute politician, and under her influence, the empire maintained its stability. Jahangir’s focus on art and culture did not come at the expense of governance; he maintained the administrative and military apparatus that Akbar had established, ensuring the continued prosperity of the empire.

Shah Jahan

Shah Jahan, Jahangir’s son, is best known for his architectural achievements, particularly the construction of the Taj Mahal, a monument of unparalleled beauty built in memory of his wife, Mumtaz Mahal. His reign marked the peak of Mughal architectural splendor, with numerous grand structures, including the Red Fort and the Jama Masjid in Delhi, exemplifying the empire’s wealth and sophistication.

Shah Jahan’s reign marked the peak of Mughal architecture, symbolizing the empire’s opulence and grandeur. The Taj Mahal, often considered one of the wonders of the world, stands as a testament to the artistic and architectural prowess of the Mughal era. However, Shah Jahan’s reign was not without its challenges. His later years were overshadowed by a debilitating illness, which sparked a brutal war of succession among his sons. Aurangzeb emerged victorious, imprisoning his father in the Agra Fort, where Shah Jahan spent the last years of his life gazing at the Taj Mahal, the monument of his undying love for Mumtaz Mahal.

Shah Jahan’s focus on monumental architecture came at a cost. The vast sums spent on construction projects strained the empire’s finances, setting the stage for economic difficulties in the subsequent reign.

Aurangzeb

Aurangzeb, the third son of Shah Jahan, is one of the most controversial figures in Mughal history. His reign marked a departure from the policies of his predecessors, especially in terms of religious tolerance. Aurangzeb expanded the Mughal Empire to its greatest territorial extent, but his rigid orthodoxy and persecution of non-Muslims alienated many of his subjects. He reintroduced the jizya (a tax on non-Muslims) and destroyed several Hindu temples, actions that sparked numerous revolts.

Aurangzeb’s relentless military campaigns in the Deccan, coupled with his harsh policies, drained the empire’s resources and weakened its administrative structure. The long wars in the south stretched the empire’s military thin and created a power vacuum in the north, which was exploited by emerging regional powers like the Marathas and the Sikhs.

Aurangzeb’s reign, though marked by expansion, sowed the seeds of the empire’s decline. His death in 1707 left the empire vast but unstable, setting the stage for the eventual disintegration of Mughal authority across India.

III. The Extent of the Mughal Empire:

Geographical Reach

At its zenith under Aurangzeb, the Mughal Empire stretched from the northern frontiers of modern-day Afghanistan to the southern tip of the Indian subcontinent, encompassing nearly the entire region. The empire’s vastness brought together a diverse population of different languages, religions, and cultures under a central authority. Managing such a vast and varied empire required a sophisticated administrative system, which the Mughals developed and refined over time.

The empire was divided into provinces, or subahs, each governed by a subahdar who was responsible for maintaining law and order, collecting taxes, and overseeing local administration. These provinces were further divided into districts (sarkars) and sub-districts (parganas), creating a highly organized and hierarchical system of governance that allowed the Mughals to maintain control over their extensive territories.

Cultural Integration

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Mughal Empire was its ability to integrate and accommodate the diverse cultures and religions of its vast territories. The Mughals, particularly under Akbar, actively promoted a policy of cultural synthesis. Akbar’s marriage alliances with Rajput princesses and his patronage of Hindu, Persian, and Islamic scholars exemplify the empire’s inclusive approach.

The Mughal court became a melting pot of Persian, Central Asian, and Indian influences, which was reflected in the empire’s art, architecture, and literature. The Mughals also adopted and adapted local customs and traditions, which helped them gain the loyalty of their subjects and secure the stability of their empire.

This cultural integration was not without its challenges, however. The later years of Aurangzeb’s reign saw a shift towards religious orthodoxy, which created tensions and divisions within the empire. Despite these challenges, the legacy of the Mughals’ cultural integration is still evident in the rich tapestry of India’s cultural heritage today.

IV. Achievements and Cultural Contributions:

Art and Architecture

The Mughal Empire is perhaps best known for its monumental contributions to art and architecture. The Mughals synthesized Persian, Indian, and Islamic architectural styles to create some of the most iconic structures in the world. The Taj Mahal, built by Shah Jahan, is the most famous example, combining Islamic calligraphy, Persian gardens, and Indian inlay work to create a masterpiece of symmetry and grace.

Other significant architectural achievements include the Red Fort in Delhi, the Jama Masjid, and Humayun’s Tomb, which served as a prototype for the Taj Mahal. These structures not only served as royal residences and places of worship but also as symbols of the Mughal Empire’s power and grandeur.

The Mughals also made significant contributions to the development of landscape architecture, as seen in the extensive use of gardens in their palaces and forts. The Mughal garden, or charbagh, with its quadrilateral layout symbolizing paradise, became a hallmark of Mughal architecture.

Literature and Language

The Mughal court was a center of cultural and intellectual life, attracting poets, historians, and scholars from across the Muslim world. Persian was the language of administration and high culture in the Mughal Empire, and it flourished under the patronage of the emperors. The Mughal period saw the production of some of the most important works of Persian literature, including the Akbarnama and the Ain-i-Akbari, which provide invaluable insights into the history and administration of the empire.

In addition to Persian, the Mughals also promoted the use of local languages. Urdu, which developed as a result of the blending of Persian, Arabic, and local languages, became a significant cultural and literary language during this period. The Mughals’ promotion of literature in multiple languages contributed to the rich cultural diversity of the Indian subcontinent.

Religious Tolerance

Akbar’s policy of religious tolerance, or Sulh-i-Kul, was one of the most notable aspects of his reign. Akbar recognized that ruling a diverse empire required a policy that went beyond mere tolerance; he sought to foster a sense of unity among his subjects by encouraging dialogue and understanding among different religious communities.

Akbar’s establishment of the Ibadat Khana (House of Worship) at Fatehpur Sikri, where scholars of different faiths could engage in discussions, exemplifies his commitment to religious pluralism. He even attempted to create a syncretic religion, Din-i Ilahi, which sought to combine the best elements of various faiths. Although this religion did not survive his reign, it reflects Akbar’s innovative approach to governance.

Aurangzeb, however, took a more orthodox approach to religion, reintroducing the jizya tax on non-Muslims and enforcing Islamic law more strictly. This shift contributed to growing discontent among the empire’s non-Muslim subjects and fueled resistance movements that would later challenge Mughal authority.

Mughal Painting

Mughal painting, which emerged under Akbar’s patronage, represents one of the most significant achievements of the empire in the arts. Mughal miniatures, known for their intricate detail, vibrant colors, and delicate brushwork, often depicted courtly scenes, battles, and religious narratives. This art form blended Persian techniques with Indian themes, resulting in a unique and highly refined style.

Prominent painters like Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd al-Samad were invited to the Mughal court, where they trained Indian artists and helped develop the distinctive Mughal style. The Akbarnama and the Hamzanama are among the most celebrated examples of Mughal miniature painting, showcasing the empire’s artistic achievements.

V. Economic and Military Might:

Trade and Economy

The Mughal Empire’s economic prosperity was largely due to its strategic position in global trade networks. The empire controlled key trade routes that connected the East with the West, facilitating the flow of goods, spices, textiles, and precious metals. Indian cotton, silks, and indigo were highly prized in European markets, while the Mughals imported luxury goods like Persian carpets, Chinese porcelain, and Arabian horses.

The Mughal administration implemented an efficient revenue system, largely based on agricultural production. Akbar’s revenue reforms, known as the Zabt system, assessed taxes based on the productivity of the land, ensuring a steady flow of income to the imperial treasury. The wealth generated from agriculture and trade allowed the Mughal emperors to fund their ambitious architectural projects and maintain a large standing army.

The Mughal Empire also fostered urbanization, with cities like Delhi, Agra, and Lahore becoming major centers of commerce and culture. These cities attracted merchants, artisans, and scholars from across the world, contributing to the empire’s cosmopolitan character.

Military Innovations

The Mughal military was a formidable force, known for its use of advanced technology and innovative tactics. The Mughals were among the first in India to use gunpowder extensively in warfare, giving them a significant advantage over their rivals. Babur’s victory at the Battle of Panipat, for instance, was largely due to his effective use of artillery.

The Mughals also developed a highly organized military structure, with a strong cavalry, well-trained infantry, and an effective use of war elephants. The Mansabdari system, introduced by Akbar, was a key element of Mughal military organization. It was a hierarchical system where officers, known as Mansabdars, were granted land revenues in return for maintaining a certain number of troops for the emperor’s service.

Naval power, although less emphasized than the land forces, was also crucial, particularly in controlling trade routes and coastal territories. The Mughals developed a strong naval presence, especially under Aurangzeb, who sought to counter the growing influence of European powers like the Portuguese and the British. The Mughal navy, though not as advanced as its European counterparts, played a key role in maintaining the empire’s dominance over the Indian Ocean trade.

In addition to technological advancements, the Mughal military was known for its ability to adapt and incorporate diverse fighting styles and tactics from across its vast empire. This adaptability, combined with a well-organized military structure, made the Mughal army one of the most formidable forces in the world during its time.

VI. Wars and Conflicts:

Throughout its existence, the Mughal Empire engaged in numerous wars, including conflicts with regional powers like the Marathas, Sikhs, and Rajputs, and faced external threats from the Safavids and the British East India Company.

Major Battles

The Mughal Empire was built and maintained through a series of significant battles and military campaigns. Apart from the Battle of Panipat, which established the Mughal foothold in India, several other conflicts were pivotal in shaping the empire’s destiny. For example, the Battle of Khanwa in 1527 was crucial in solidifying Babur’s power after defeating the Rajput confederacy led by Rana Sanga. Similarly, the Battle of Haldighati in 1576, fought between Akbar’s forces and Maharana Pratap, symbolized the empire’s continued expansion and dominance over the Rajput kingdoms.

Internal conflicts, such as the wars of succession among Shah Jahan’s sons, also played a significant role in shaping the Mughal Empire’s history. These power struggles often weakened the empire, draining resources and leading to periods of instability.

External Threats

Throughout its history, the Mughal Empire faced significant external threats from neighboring powers. The Safavids of Persia, the Uzbeks, and the rising Maratha Confederacy posed continuous challenges to Mughal dominance. The Deccan Wars, fought against the Sultanates of the Deccan region, were particularly draining, both in terms of resources and manpower. Aurangzeb’s protracted campaigns in the Deccan, while expanding the empire’s territory, ultimately overextended the empire’s resources, contributing to its decline.

The Mughal Empire’s interactions with European powers, particularly the Portuguese, Dutch, and British, also introduced new dynamics. Initially, the Mughals saw the European traders as minor players in the Indian Ocean trade network. However, by the 17th century, the growing influence of the British East India Company began to pose a significant challenge to Mughal authority, eventually leading to the empire’s decline.

VII. The Dark Side of the Mughal Empire:

Beneath the cultural splendor lies a dark underbelly marked by religious persecution, cruelty, and subjugation. Emperors like Aurangzeb ordered the destruction of Hindu temples, imposed oppressive taxes, and enforced conversions through coercion.

Religious Persecution

While the Mughal Empire is often celebrated for its cultural achievements and architectural wonders, it also had a darker side, particularly in terms of religious intolerance. Aurangzeb’s reign, in particular, is often cited as a period of heightened religious persecution. His strict enforcement of Islamic law, the destruction of Hindu temples, and the reintroduction of the jizya tax on non-Muslims led to widespread resentment and rebellions among the empire’s Hindu subjects.

These policies marked a sharp departure from the religious tolerance practiced by his predecessors, especially Akbar. The resulting alienation of large segments of the population contributed to the weakening of the empire’s social cohesion and laid the groundwork for the rise of regional powers like the Marathas and the Sikhs, who would later challenge Mughal dominance.

Harsh Policies and Rebellions

Aurangzeb’s harsh policies, including his aggressive military campaigns in the Deccan and his repressive measures against non-Muslim communities, sparked numerous rebellions. These uprisings, including the Maratha resistance under Shivaji and the Sikh resistance in Punjab, further strained the empire’s resources and military.

Aurangzeb’s focus on expanding the empire at any cost, coupled with his religious orthodoxy, not only depleted the empire’s treasury but also alienated many of his subjects. This discontent eventually contributed to the empire’s fragmentation and decline after his death.

VIII. The Decline and Fall of the Mughal Empire

Internal Weaknesses

The decline of the Mughal Empire can be attributed to a combination of internal weaknesses and external pressures. Aurangzeb’s death in 1707 left a vast empire with a weakened administrative structure and a drained treasury. The wars of succession that followed his death further destabilized the empire, as rival claimants to the throne engaged in bloody conflicts that eroded the central authority.

The later Mughal emperors, often referred to as the “later Mughals,” lacked the political acumen and military prowess of their predecessors. They became increasingly dependent on regional governors and military commanders, who began to assert their independence. The breakdown of the Mansabdari system, which had been the backbone of the Mughal administration, further weakened the empire’s control over its territories.

European Colonization

The growing influence of European powers, particularly the British, also played a crucial role in the decline of the Mughal Empire. The British East India Company, initially a trading entity, gradually expanded its military and political power in India. The Battle of Plassey in 1757, where the British defeated the Nawab of Bengal, marked the beginning of British political dominance in India.

The British, using a combination of diplomacy, military force, and economic exploitation, steadily expanded their control over India, often exploiting the weaknesses of the Mughal Empire and the ambitions of its regional governors. By the early 19th century, the Mughal emperor was little more than a symbolic figure, with real power residing in the hands of the British.

The Final Collapse

The final blow to the Mughal Empire came with the Indian Rebellion of 1857, also known as the Sepoy Mutiny. Although the rebellion was initially sparked by discontent among Indian soldiers in the British East India Company’s army, it quickly grew into a widespread revolt against British rule. The rebels sought to restore the Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah II, to power, but the uprising was ultimately crushed by the British.

In the aftermath of the rebellion, the British formally abolished the Mughal Empire and exiled Bahadur Shah II to Rangoon, marking the end of over three centuries of Mughal rule in India. The British Crown took direct control of India, ushering in the era of the British Raj.

IX. Legacy of the Mughal Empire

The legacy of the Mughal Empire is complex and multifaceted. On one hand, the Mughals left an indelible mark on Indian culture, art, and architecture. The Taj Mahal, the Red Fort, and numerous other monuments stand as enduring symbols of the empire’s artistic achievements. The Mughal period also saw the flowering of a rich cultural synthesis, with the blending of Persian, Indian, and Islamic traditions that continue to influence Indian society today.

The Mughals also made significant contributions to the development of a centralized administrative system, which influenced subsequent Indian rulers and even the British colonial administration. The Persian language and literature flourished under the Mughals, leaving a lasting impact on the Indian linguistic landscape, particularly in the development of Urdu.

However, the Mughal legacy is also marked by episodes of religious intolerance and oppressive policies, particularly under Aurangzeb. These aspects of Mughal rule contributed to social and political tensions that would shape the course of Indian history long after the empire’s decline.

The Mughal Empire, with its blend of cultural achievements, architectural marvels, and complex history, remains a defining chapter in the history of the Indian subcontinent. While it is remembered for its contributions to art, culture, and administration, it is also a reminder of the challenges of empire-building in a diverse and vast land. The Mughal Empire’s legacy, both positive and negative, continues to shape the identity and history of India to this day.