On the windswept Coromandel Coast of Tamil Nadu, where the Bay of Bengal crashes against granite outcrops, rises a city of stone. Mahabalipuram, or Mamallapuram, is less a city of brick and mortar than of carved rock and vision. Founded and adorned by the Pallava dynasty (6th–8th centuries CE), it became a monumental statement of South Indian kingship, faith, and artistry; a city designed to astonish both mortals and gods.

Origins and Name

The name Mahabalipuram is often linked to the asura king Mahabali, but inscriptions and Pallava records refer to it as Mamallapuram (“city of the great wrestler”), after the Pallava king Narasimhavarman I (630–668 CE), titled Mamalla for his prowess.

While the site may have had earlier settlements, it was under the Pallavas that it emerged as a major port city and artistic center, connected to maritime trade routes stretching across the Bay of Bengal to Southeast Asia.

Mahabalipuram as a Port City

By the 7th century CE, Mahabalipuram was a thriving emporium of the seas. Arab, Chinese, and Southeast Asian merchants frequented its harbors. Inscriptions note the Pallavas’ diplomatic and cultural exchanges with Srivijaya (Indonesia), Cambodia, and Siam, and many scholars see Mahabalipuram as both a trading hub and a cultural exporter of Indian art and religion into Southeast Asia.

The Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang mentions the Pallava kingdom (though not Mahabalipuram by name), praising its monasteries and temples, and highlighting its role in Buddhism’s spread to Southeast Asia.

Rock-Cut Wonders

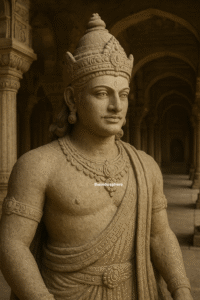

Mahabalipuram’s fame rests above all on its rock-cut monuments. Here the Pallavas pioneered the transformation of granite cliffs and boulders into temples, shrines, and narrative reliefs. These works mark a turning point in Indian art; from cave sanctuaries to freestanding temples.

The Five Rathas

Carved from single granite monoliths, the Pancha Rathas (Five Chariots) are shrines in the form of temple chariots, each with different architectural styles. Dedicated to the Pāṇḍava brothers and Draupadī, they demonstrate an experimental spirit, as if architects were testing models later perfected in South Indian temple architecture.

Arjuna’s Penance

The colossal relief known as Arjuna’s Penance or Bhagiratha’s Descent of the Ganga stretches across a granite cliff, depicting gods, sages, animals, and celestial beings witnessing the descent of the sacred river. It is one of the world’s largest open-air bas-reliefs, merging cosmic mythology with natural landscape.

The Shore Temple

Standing against the sea spray, the Shore Temple (8th century CE) is one of the earliest freestanding stone temples of South India. Dedicated to both Shiva and Vishnu, its twin spires symbolized Pallava power to maritime travelers approaching the coast. Marco Polo, centuries later, would marvel at this “Seven Pagodas” of Mahabalipuram, though only one temple survives intact.

Society and Religion

The Pallavas ruled a cosmopolitan society, with Shaivism as their state religion, but with strong Vaishnava and Buddhist presences. Mahabalipuram’s monuments reflect this pluralism: Shiva shrines dominate, but Vishnu’s Anantasayana (reclining on the serpent) is also carved into the rocks.

Guilds of sculptors, masons, and seafarers formed the city’s backbone, supported by the royal patronage of kings like Mahendravarman I and Narasimhavarman I. The city blended sacred space, political propaganda, and artistic experimentation, reflecting a confident, outward-looking dynasty.

Later History and Legacy

By the 9th century CE, the Cholas rose to prominence, and Mahabalipuram’s role as a capital waned. Yet the city remained an active port and a place of pilgrimage. Travelers and chroniclers from the medieval period continued to marvel at its stone marvels.

The “Seven Pagodas” legend—that six of Mahabalipuram’s great temples were swallowed by the sea, leaving only the Shore Temple; was reported by Marco Polo and European sailors. In 2004, after the Indian Ocean tsunami receded, archaeologists found submerged structures off the coast, lending weight to the old tales.

Today, Mahabalipuram is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, its monuments among the most celebrated of Indian art.

The Legacy of Mahabalipuram

Mahabalipuram’s significance lies in:

- Artistic innovation: The transition from cave shrines to structural temples.

- Cosmopolitan exchange: Its role as a Pallava maritime hub, linking India with Southeast Asia.

- Mythic and historic memory: A city where Arjuna’s penance, the Ganga’s descent, and Pallava glory were carved into living stone.

Unlike Gandhāra’s urban ruins or Varanasi’s continuous sacred cityscape, Mahabalipuram endures as a stone chronicle; a record of a dynasty’s ambition and the artistic heights of early medieval India.