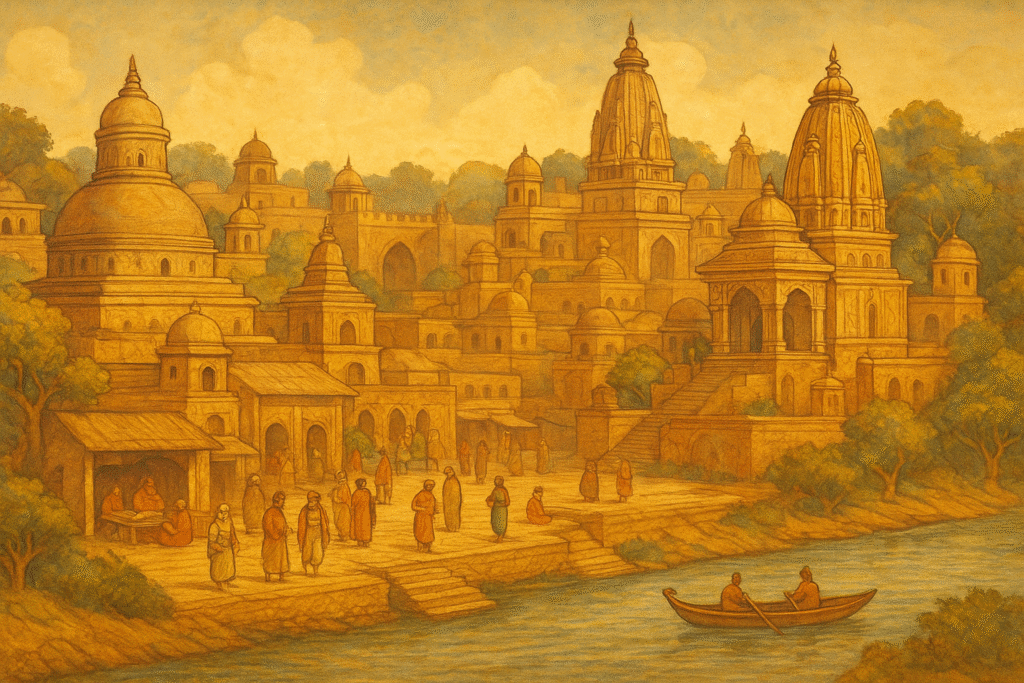

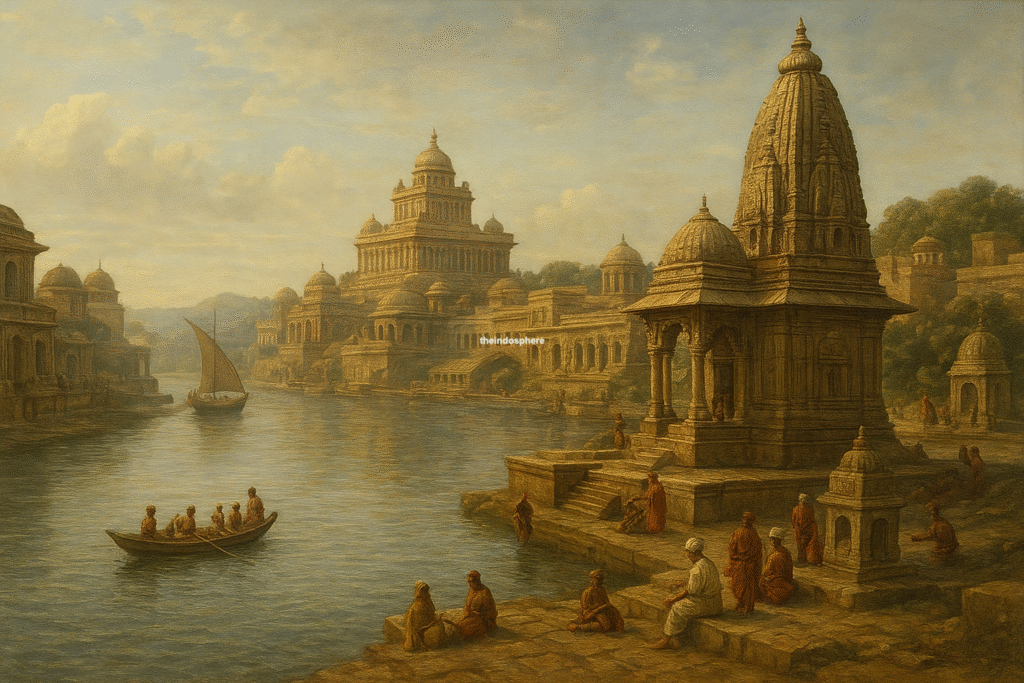

On the banks of the Yamuna River in present-day Uttar Pradesh lies Mathura, one of India’s oldest and most storied cities. Known in ancient texts as a sacred site, a thriving trade hub, and a crucible of artistic innovation, Mathura’s history stretches from Vedic lore to imperial grandeur, from spiritual efflorescence to cultural resilience. Revered as the birthplace of Bhagwan Krishna, the city’s significance is rooted not only in sacred narratives but also in archaeology, inscriptions, and recorded history.

Ancient Roots and Early References

Mathura is mentioned in the Mahabharata as Madhupura or Madhura, the capital of the Shurasena kingdom ruled by King Ugrasena and later by Krishna himself. In Buddhist scriptures such as the Anguttara Nikaya, it appears as a prosperous urban settlement. Its strategic location made it a vital gateway city, connecting the Gangetic plain to trade routes leading westward into Gujarat and Central Asia.

Jain tradition too holds Mathura sacred: the Kalpa Sutra records the birth of the 22nd Tirthankara, Neminatha, near the city. Archaeological evidence further confirms continuous settlement from at least the 6th century BCE, placing Mathura among the oldest urban centers of the subcontinent.

Mathura as a Political and Cultural Hub

By the 6th century BCE, Mathura was a bustling city of merchants, craftsmen, and monks, frequently mentioned in the Jātakas. Under the Mauryan Empire (4th–2nd century BCE), it became a provincial hub; Ashokan inscriptions attest to imperial patronage of Buddhism.

In the centuries that followed, Mathura was contested by the Shungas, Indo-Greeks, and Śakas before reaching its zenith under the Kushan dynasty (1st–3rd century CE). The Greek geographer Ptolemy knew it as “Modoura,” a major city on the Yamuna. Indo-Greek coins of Menander and Apollodotus, discovered in the region, reveal the cosmopolitan networks that shaped Mathura’s identity.

The Kushan Zenith

The reign of Kanishka and his successors (2nd century CE) marked Mathura’s golden age. As one of the three great centers of the Kushan Empire, alongside Gandhara and Purushapura, it blossomed as a hub of trade, religion, and art.

- Art: The celebrated Mathura school of sculpture emerged, producing bold, sensuous figures carved in distinctive red sandstone. Unlike Gandhara’s Greco-Roman aesthetic, Mathura’s art was unmistakably Indian, laying the foundation for future iconography.

- Religion: Mathura became a rare crossroads where Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism flourished simultaneously. Temples to Krishna-Vasudeva stood alongside stupas and Jain shrines. Inscriptions reveal generous patronage from rulers, merchants, and artisans alike.

- Trade: Situated on caravan routes, Mathura linked India with Central Asia and beyond. Cotton textiles, stonework, and terracotta from its workshops reached markets across the subcontinent and into the Roman world.

Gupta Age and Beyond

During the Gupta Empire (4th–6th century CE), Mathura enjoyed another cultural flowering. Temples dedicated to Vishnu and Shiva, alongside elegant Buddhist and Jain sculptures, reflected a refinement that would shape Indian temple architecture for centuries.

Even as dynasties changed, the Hunas, Gurjara-Pratiharas, Delhi Sultans, and Mughals; Mathura’s sanctity endured, anchored in Krishna devotion. The Bhakti movement of the medieval period amplified its stature as the heart of Vaishnava spirituality.

The Sacred City of Krishna

For Hindus, Mathura is most sacred as Krishna’s birthplace. Texts like the Bhagavata Purana and Harivamsa recount his birth in Mathura’s prison, his childhood in nearby Gokul, and his eventual slaying of Kamsa. This mythology infused the city with irresistible religious magnetism.

Temples to Krishna-Vasudeva are attested as early as the Kushan period. Despite invasions, Mahmud of Ghazni’s raids in the 11th century, Aurangzeb’s demolition of the Janmabhoomi temple in the 17th century the site remained central to Hindu devotion, rebuilt time and again under Rajput and Maratha patronage.

A Cradle of Indian Art

Mathura’s greatest cultural legacy lies in its art. Between the 2nd century BCE and 3rd century CE, its sculptors pioneered anthropomorphic depictions of Hindu deities, Buddhas, and Jain Tirthankaras.

- Hindu Art: The earliest images of Krishna, Vishnu, and Shiva were sculpted here, defining the visual language of Hindu worship.

- Buddhist Art: Mathura Buddhas broad-shouldered, smiling, lightly draped differed strikingly from the Greco-Buddhist figures of Gandhara.

- Jain Art: Towering statues of Tirthankaras, serene and abstract, became icons of Jain devotion.

Art historians have called Mathura the “mother of Indian iconography,” for its forms spread across India, influencing sculpture at Sanchi, Bharhut, and later Gupta temples.

A Meeting Ground of Faiths

Mathura’s sacred landscape was never singular.

- Hinduism: Celebrated as one of the Sapta Puri (seven holy cities), its pilgrimage circuits extend into Vrindavan, where Krishna’s childhood lilas are remembered.

- Buddhism: The Chinese pilgrim Faxian (5th century CE) described thousands of monks and monasteries here, while Xuanzang (7th century CE) noted its stupas even as Hinduism resurged.

- Jainism: Mathura remained a bastion of Jain worship, with inscriptions recording donations to temples by both men and women, merchants and artisans alike.

Decline and Resilience

By the late Gupta period, Mathura’s political role diminished, but its sanctity never faded. Repeated invasions brought destruction: Mahmud of Ghazni plundered its temples in 1018 CE, and Aurangzeb built the Gyanvapi mosque over Krishna’s Janmabhoomi temple in the 17th century. Yet devotion endured, with later rulers ensuring its revival.

Mathura Today

In modern India, Mathura continues to thrive as a pilgrimage city. The Krishna Janmabhoomi temple, Vishram Ghat, and the forested groves of Vrindavan attract millions of devotees every year. Its unearthed sculptures fill museums worldwide, bearing silent witness to a city that once gave form to India’s gods.

If Varanasi is the “city of light,” Mathura may rightly be called the “city of love and devotion.” Here, myth became geography, faith became sculpture, and cultures converged into an enduring legacy.