1. Early Life and Education

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, later known as Mahatma Gandhi, was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, Gujarat. His father, Karamchand Gandhi, served as the chief minister of Porbandar, while his mother, Putlibai, was a devout follower of Vaishnavism and Jain principles, including nonviolence and vegetarianism. Gandhi’s upbringing was steeped in religious and ethical traditions that would later shape his leadership and moral philosophy.

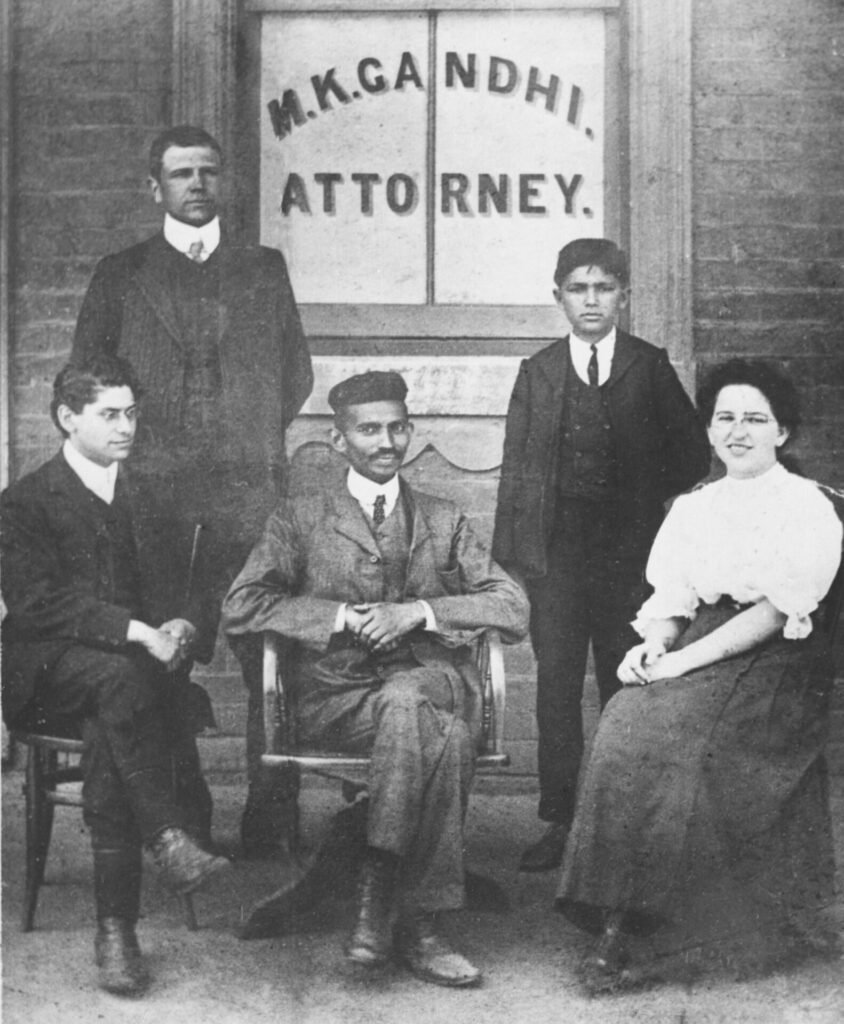

In 1888, at the age of 19, Gandhi traveled to London to study law at University College London. Despite initial struggles to adapt to British customs, he completed his studies in 1891 and returned to India. However, his attempts to establish a law practice were largely unsuccessful, and in 1893, he accepted an opportunity to work in South Africa—a decision that would transform his life.

2. The South African Experience: Birth of Satyagraha

Upon arriving in South Africa, Gandhi was exposed to rampant racial discrimination against the Indian community. The turning point came when he was thrown off a train in Pietermaritzburg for refusing to move from a first-class compartment despite holding a valid ticket. This personal experience of injustice led Gandhi to stay in South Africa and lead efforts against racial discrimination.

In South Africa, Gandhi formulated the philosophy of Satyagraha—a form of nonviolent resistance aimed at confronting injustice through truth and moral courage. Over two decades, he led campaigns against discriminatory laws, such as the pass system, and fought for the civil rights of Indian immigrants. These movements not only secured victories for the Indian community but also established Gandhi as a leader capable of mobilizing mass movements through nonviolence.

3. Return to India and Entry into the Independence Movement

Gandhi returned to India in 1915, where he was warmly welcomed as a hero of South African Indians’ rights. Under the mentorship of Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a senior leader of the Indian National Congress (INC), Gandhi familiarized himself with the political landscape of colonial India.

Initially, he focused on local issues such as the Champaran Satyagraha in 1917, where he fought for the rights of impoverished indigo farmers in Bihar. The movement’s success marked the first significant victory in Gandhi’s Indian campaigns and raised his profile nationally.

In 1919, the British government enacted the Rowlatt Act, which allowed for the detention of individuals suspected of sedition without trial. This provoked widespread outrage and led to the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, where British troops opened fire on a peaceful gathering, killing hundreds. This event marked a decisive shift in Gandhi’s approach, as he moved from supporting moderate constitutional reforms to advocating for mass civil disobedience against British rule.

4. The Non-Cooperation Movement (1920-1922)

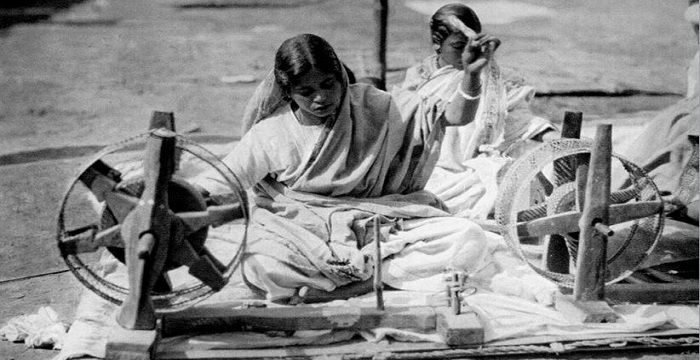

In 1920, Gandhi launched the Non-Cooperation Movement, one of the first mass movements of the Indian independence struggle. It called for Indians to boycott British goods, government institutions, and honors, while promoting swadeshi (the use of locally produced goods) and khadi (homespun cloth) as symbols of self-reliance. The movement marked the entry of ordinary Indians—peasants, laborers, and women—into the national struggle for freedom.

Gandhi’s message of nonviolence and self-reliance resonated across the country, and millions participated in boycotts, strikes, and protests. The movement, however, faced a major setback in 1922 when violence erupted in the town of Chauri Chaura, where protesters burned a police station, killing 22 policemen. Deeply disturbed by the violence, Gandhi called off the movement, believing that the country was not ready for a disciplined nonviolent struggle.

The sudden suspension of the Non-Cooperation Movement frustrated many within the Indian National Congress, particularly younger leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, who were eager to continue the fight against British rule. Despite the movement’s abrupt end, it had a lasting impact by awakening national consciousness and spreading Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence.

5. The Khilafat Movement and Gandhi’s Alliance with Muslims

During this period, Gandhi also supported the Khilafat Movement (1919-1924), which sought to protect the Ottoman Caliphate after its dissolution by European powers following World War I. Gandhi saw the Khilafat cause as an opportunity to foster Hindu-Muslim unity and strengthen the Indian independence struggle. He believed that by supporting Muslim grievances, the INC could forge a united front against British rule.

However, Gandhi’s involvement in the Khilafat Movement remains one of his more controversial decisions. Many Hindus were uneasy with his support for a pan-Islamic cause, and the movement eventually collapsed after Turkey abolished the caliphate in 1924. Gandhi’s alliance with the Khilafat leaders failed to sustain long-term Hindu-Muslim unity, and critics argue that it inadvertently heightened communal tensions in India.

6. The Malabar Rebellion (1921): A Controversial Episode

The Malabar Rebellion of 1921 in the Malabar region of Kerala was another moment that drew criticism of Gandhi’s judgment. The rebellion, initially a peasant uprising against British landlords, quickly escalated into violence between Muslim peasants (Mappilas) and Hindu landlords. Thousands were killed, and many Hindus were forcibly converted to Islam during the uprising.

Although Gandhi condemned the violence, many felt that his initial support for the Khilafat Movement had indirectly contributed to the religious tensions that fueled the rebellion. His handling of the Malabar Rebellion caused divisions within the Hindu community, and some saw it as a failure of his approach to religious unity.

7. The Civil Disobedience Movement and the Salt March (1930)

After the Non-Cooperation Movement, Gandhi briefly retreated from active politics, focusing on social reforms. However, in 1930, he re-emerged with the launch of the Civil Disobedience Movement, aimed at challenging British economic exploitation of India. The movement’s centerpiece was the Salt March, a 240-mile march from Gandhi’s Sabarmati Ashram to the coastal village of Dandi, where he symbolically defied British law by making salt from seawater.

The Salt March galvanized the Indian population, inspiring widespread acts of civil disobedience, including the refusal to pay taxes and the boycott of British goods. Gandhi was arrested, but the movement succeeded in drawing international attention to India’s independence struggle and increased pressure on the British government. Negotiations followed, but these ultimately fell short of full independence.

8. The Growing Demand for Partition and the Creation of Pakistan

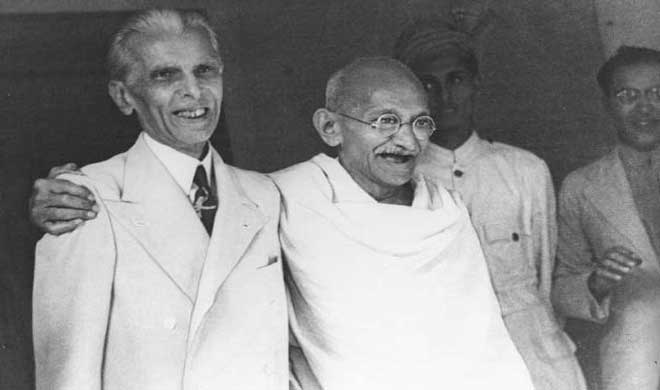

The 1930s and 1940s saw growing tensions between Hindus and Muslims in India, exacerbated by the rise of the Muslim League under the leadership of Muhammad Ali Jinnah. While Gandhi remained committed to Hindu-Muslim unity, the Muslim League increasingly advocated for the creation of a separate Muslim state, which culminated in the demand for Pakistan.

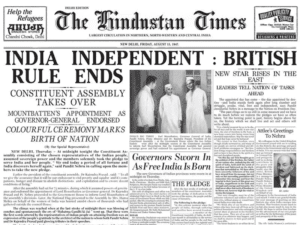

Despite Gandhi’s opposition to the idea of partition, the British government, under mounting pressure, agreed to divide India into two nations: India and Pakistan. Partition in 1947 led to unprecedented violence and one of the largest mass migrations in human history. Gandhi was deeply pained by the communal carnage and the division of the country, which he saw as a personal and political failure.

9. Assassination and Legacy

Gandhi spent his final days working tirelessly to restore peace in riot-torn regions. His efforts to protect Muslims during the Partition angered some Hindu nationalists, leading to his assassination on January 30, 1948, by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu extremist who believed Gandhi had betrayed the Hindu community.

Though Gandhi’s life ended in tragedy, his legacy endures as one of the foremost leaders of nonviolent resistance. His methods inspired civil rights movements worldwide, including the American Civil Rights Movement led by Martin Luther King Jr. and the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa.

10. The Legacy and Controversies of Gandhi

While Gandhi is celebrated as the Father of the Nation in India and a global symbol of peace and nonviolence, his career was not without controversies. His involvement in the Khilafat Movement, his handling of the Malabar Rebellion, and his perceived failure to prevent the Partition are seen as significant miscalculations. Critics argue that his idealism, though admirable, sometimes led to impractical strategies in the face of complex religious and political realities.

Nevertheless, Gandhi’s unwavering commitment to nonviolence, truth, and justice reshaped the Indian independence struggle and left an indelible mark on world history.

Conclusion

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s life was a remarkable journey from a young lawyer in South Africa to a towering figure in the global fight for justice. Though his career was marked by both successes and setbacks, Gandhi’s influence on the Indian independence movement and his philosophy of nonviolence have earned him a place among the greatest leaders in history. His legacy continues to inspire movements for freedom, equality, and human dignity around the world.