Introduction

The East India Company (EIC) began as a modest trading venture in 1600 and grew into a global power that controlled vast territories and shaped the course of world history. From its humble beginnings to its eventual downfall, the story of the EIC is one of ambition, conflict, and exploitation. This article explores the key milestones of the EIC’s journey and the individuals who played crucial roles in its history, offering a comprehensive view of its vast and complex legacy.

The Establishment of the East India Company

Foundation and Charter

The East India Company was officially established on December 31, 1600, when Queen Elizabeth I granted a royal charter to a group of 218 merchants and investors. Among these early visionaries was Sir Thomas Smythe, who served as the first governor of the Company and played a pivotal role in setting its foundational policies. The royal charter provided the Company with a 15-year monopoly on all trade east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Straits of Magellan.

The aim of the EIC was to challenge the dominance of the Portuguese and Dutch in the lucrative spice trade. With the charter came extraordinary powers, including the right to establish settlements, make treaties, wage war, and maintain its own armed forces. This blend of commercial ambition and political authority set the stage for the Company’s rise as a global entity.

Early Ventures and Challenges

The EIC’s first voyage, led by James Lancaster in 1601, was a significant milestone. Lancaster’s fleet successfully reached the East Indies, returning to England with a profitable cargo of spices. However, the early years of the EIC were far from smooth. The Portuguese, with their established naval supremacy, and the Dutch, who had formed the powerful Dutch East India Company (VOC), were fierce competitors. The EIC also faced internal challenges, such as managing investor expectations and navigating fluctuating markets.

In India, the Mughal Empire presented both an opportunity and a challenge. Captain William Hawkins arrived at the Mughal court in 1609 but failed to secure trade concessions due to opposition from Portuguese allies. However, by 1612, the EIC’s fortunes began to change. Hawkins’ successor, Sir Thomas Roe, became the first official ambassador to the Mughal court and successfully negotiated with Emperor Jahangir, securing trading privileges and the establishment of the Company’s first factory in Surat.

Securing a Foothold in India

Expansion Through Trading Posts

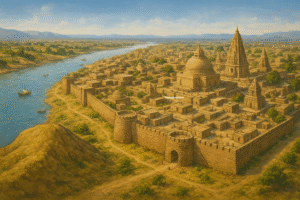

The EIC’s foothold in India expanded steadily in the 17th century. Key trading posts were established in Madras (1639), Bombay (1668), and Calcutta (1690). These locations were strategically chosen for their access to ports and proximity to lucrative trade routes. Notable figures like Francis Day (Madras) and Gerald Aungier (Bombay) played critical roles in laying the foundations of these settlements, which would later evolve into major urban centers.

The acquisition of Bombay from the Portuguese in 1661—as part of Catherine of Braganza’s dowry to King Charles II—was a turning point. By 1668, the British Crown had transferred control of Bombay to the EIC, which transformed it into a thriving trading hub under the leadership of Aungier. Meanwhile, Calcutta’s growth was spearheaded by Job Charnock, often credited as the founder of the city.

Indian Allies and Collaborators

The success of the EIC in India would not have been possible without the support of local intermediaries and allies. Merchants, bankers, and local rulers often collaborated with the Company, either for mutual benefit or under duress. Key Indian figures, such as the Jagat Seth banking family in Bengal, financed the Company’s ventures and provided logistical support. Additionally, Indian soldiers (sepoys) became a crucial component of the EIC’s private army, which grew exponentially in size and power.

The Transformation from Traders to Rulers

The Decline of the Mughal Empire

By the early 18th century, the once-mighty Mughal Empire was in decline. Regional powers like the Marathas, Nawabs, and other princely states filled the power vacuum, creating a fragmented political landscape. The EIC capitalized on this instability to expand its influence through both diplomacy and military force.

Key Battles: Plassey and Buxar

The turning point came in 1757 with the Battle of Plassey. Robert Clive, an ambitious military leader, orchestrated a victory against the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daulah. Clive’s strategic alliance with Mir Jafar, a discontented court noble, ensured the EIC’s success. This victory not only secured Bengal’s wealth but also marked the beginning of British political dominance in India.

In 1764, the Battle of Buxar further solidified the EIC’s authority. The Company’s forces defeated a coalition of Indian rulers, including Shuja-ud-Daula (Nawab of Awadh) and the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II. The Treaty of Allahabad (1765) granted the EIC “Diwani rights,” allowing it to collect revenue in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. With this, the EIC transformed from a trading enterprise into a governing entity.

The Role of Indian Officials

While the EIC imposed its authority, many Indian officials and administrators worked within its framework. Figures like Mir Jafar and later Mir Qasim initially allied with the Company, though often at great cost to their own autonomy. Indian bureaucrats, zamindars (landowners), and soldiers became integral to the EIC’s operations, further entrenching its power.

Governance and Exploitation

Administrative Reforms and Revenue Systems

The governance of British India under the EIC was marked by a mix of administrative reforms and ruthless exploitation. Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of India (1773–1785), introduced significant changes in governance, including codifying laws and streamlining revenue collection. Lord Cornwallis later implemented the Permanent Settlement, which fixed land taxes but impoverished Indian farmers and created a rigid landlord system.

Economic and Cultural Impact

The EIC’s economic policies drained India’s wealth and stifled local industries. Traditional crafts, such as Bengal’s textile industry, suffered due to the influx of British manufactured goods. At the same time, figures like Thomas Babington Macaulay pushed for Western education reforms, replacing traditional systems with English-based curricula. Missionaries like Charles Grant sought to convert Indians to Christianity, exacerbating cultural tensions.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the End of the EIC

Causes of the Rebellion

The 1857 uprising, also known as the Sepoy Mutiny, was fueled by multiple grievances:

- Economic Exploitation: Heavy taxation and the destruction of local industries left many Indians impoverished.

- Cultural Insensitivity: Policies like the use of cow and pig fat in rifle cartridges offended both Hindu and Muslim soldiers.

- Military Discontent: Sepoys, who formed the backbone of the EIC’s army, felt alienated by discriminatory practices.

Key Events and Figures

The rebellion began with Mangal Pandey’s defiance in Barrackpore and quickly spread across northern India. Leaders like Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, Tantia Tope, and Bahadur Shah Zafar rallied resistance against the British. While the rebellion was ultimately crushed, it exposed the EIC’s inability to maintain control.

The British Crown Takes Over

In 1858, the British Crown formally dissolved the East India Company, transferring its administrative functions to the government. The Government of India Act 1858 established the British Raj, marking the beginning of direct imperial rule. Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India in 1876, symbolizing the shift in power.

The Legacy of the East India Company

Positive and Negative Aspects

For Britain:

- Positive: The EIC’s ventures enriched Britain, fueling the Industrial Revolution and expanding its global influence.

- Negative: The exploitative practices of the EIC tarnished Britain’s reputation and sowed the seeds of anti-colonial movements.

For India:

- Positive: The EIC introduced centralized governance, modern infrastructure, and Western education, laying the groundwork for India’s modernization.

- Negative: Its policies drained India’s wealth, destroyed local industries, and exacerbated social and economic inequalities.

Modern Reflections

Today, the EIC’s legacy is a subject of debate. While it is studied as a pioneering corporate entity, it is also criticized for its role in perpetuating colonial exploitation. The story of the EIC serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked corporate power.

Conclusion

The East India Company’s transformation from a trading corporation to an imperial power is a story of ambition, resilience, and exploitation. Its legacy is deeply intertwined with the histories of Britain, India, and the wider world. By understanding the EIC’s impact, we gain insight into the forces that shaped modern geopolitics and continue to influence global systems today.