The Birth of a Kingdom in Bengal

Before the 7th century CE, Bengal was not united under one ruler. The fertile lands of the Ganga-Brahmaputra delta were divided among small chiefs and tribal polities, often overshadowed by the great powers of the north — the Guptas, the Vakatakas, and later the Maukhari and Pushyabhuti dynasties of the Ganga plains.

It was in this fragmented landscape that Shashanka Deva emerged. Rising from the region known as Gauda (western Bengal, near present-day Murshidabad), Shashanka consolidated surrounding territories through conquest and diplomacy. By around c. 600 CE, he had made Karnasuvarna his capital, and Bengal, for the first time in history, had a king who ruled it as a unified realm.

This is why historians often call Shashanka the first historical king of Bengal.

The Shadowy Origins of a King

The historical record of Shashanka’s early life is fragmentary. His rise comes into view in the early 7th century, during a period of intense struggle for supremacy in northern India. The great Gupta Empire had collapsed a century earlier, leaving behind a political vacuum. The Gauda region of Bengal, with its fertile plains and strategic trade routes, became contested ground for ambitious rulers.

Shashanka’s ascent seems to have been swift and forceful. Inscriptions describe him as Maharajadhiraja Shashanka Deva, a sovereign ruler who held sway over large parts of Bengal and beyond. His capital was at Karnasuvarna, near present-day Murshidabad in West Bengal, from where he consolidated his dominion.

A Rival of Empires

Shashanka’s reign coincided with one of India’s most fascinating political rivalries. To his west, Harsha of Kanauj (Harshavardhana) was expanding his empire across the Gangetic plains. To his east, the region of Kamarupa (Assam) was asserting its independence under King Bhaskaravarman. In this triangular contest, Shashanka stood as Bengal’s champion, determined to keep his kingdom from being swallowed by larger powers.

Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang), who traveled through India in the 7th century, paints a vivid picture of this world. His writings suggest that Shashanka resisted Harsha’s advances and sought alliances to secure his rule. Though Harsha’s court historians depict Shashanka as an adversary, this very hostility underscores his significance—he was not a minor chief but a monarch capable of standing against India’s most formidable rulers.

Was Shashanka Really a Destroyer of Buddhism?

Shashanka’s name is often entangled in religious debate. Later Buddhist sources accuse him of hostility toward Buddhism, claiming he cut down the Bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya and removed sacred relics. Some even describe him as an enemy of the faith. Yet these accounts, largely written from the perspective of Harsha’s allies, are difficult to verify.

But what is the truth?

- His copperplate inscriptions invoke Shiva and call him a devout Shaiva, but they do not mention hostility toward Buddhism.

- Archaeology shows that Buddhist monasteries in Bengal and Bihar continued to flourish after his reign.

- Scholars suggest that Xuanzang and later Buddhist chroniclers may have exaggerated his hostility, because Shashanka opposed Harsha, who was a supporter of Buddhism.

What is certain is that Shashanka was a staunch patron of Shaivism. Inscriptions issued under his authority invoke Bhagwan Shiva, and coins minted in his reign often bear Shaivite symbols, such as the bull Nandi. This clear preference for Shaivism may have been exaggerated by his rivals into accusations of persecution.

So while Shashanka was certainly a Shaivite ruler who promoted Hinduism, the evidence that he deliberately set out to “destroy Buddhism” is weak and likely politicized.

Karnasuvarna: The Forgotten Capital

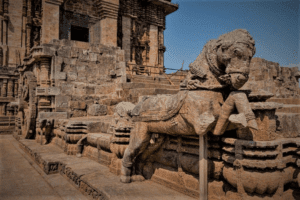

Shashanka ruled from Karnasuvarna, located near modern Murshidabad in West Bengal. Today, little remains except mounds and ruins, but excavations reveal the outline of a prosperous city.

Karnasuvarna was a riverine capital, controlling routes along the Ganga. A hub of trade, with connections stretching to ports in Bengal and Odisha. A religiously vibrant city, with both Shaiva temples and evidence of Buddhist monasteries nearby.

It was from this city that Shashanka coordinated his campaigns against Harsha and asserted Bengal’s independence.

The Birth of Bengal’s Political Identity

Despite the polemics, Shashanka’s true legacy lies in the political consolidation of Bengal. For the first time, the fragmented regions of Gauda, Vanga, and Samatata came under the authority of a single ruler who projected his power on the broader Indian stage. His reign marked the beginning of Bengal’s emergence as a distinct historical and cultural entity—a trajectory that would later produce the Palas, Senas, and ultimately the Bengal Sultanate.

Archaeological finds and inscriptions from his era reveal a kingdom engaged in trade, agriculture, and temple-building. The site of Karnasuvarna has yielded remnants of fortifications and religious structures, hinting at a capital city that was both prosperous and politically central.

The End of a Dynasty

Shashanka’s death, around 625 CE, plunged Bengal once more into uncertainty. His successors proved unable to withstand the pressure of neighboring powers. Harsha eventually extended his influence eastward, and Kamarupa too asserted control over parts of Bengal. Yet Shashanka’s role as the first true king of Bengal was not forgotten.

Centuries later, chronicles and folk traditions remembered him as the founder of Bengal’s sovereignty. Even in debates over his religious policies, his stature as a formidable monarch remains uncontested.

Legacy of a Forgotten Monarch

In the grand narratives of Indian history, Shashanka Deva is often overshadowed by figures like Harsha or the later Palas. Yet, to understand Bengal’s identity as a land that could stand independently—politically, culturally, and religiously—one must begin with Shashanka.

He was a ruler who rose in a fragmented age and left behind the blueprint for Bengal’s kingship. His reign, brief though it was, ensured that Bengal was not merely a frontier province of others’ empires, but a kingdom in its own right.