In the rolling hills of what is today northern Pakistan, where the Margalla range breaks into fertile valleys, lie the ruins of a city that once stood at the beating heart of ancient civilization. Taxila—Takṣaśilā in Sanskrit, “the hill of Takṣa”—was no ordinary city. For over a thousand years, it served as a political prize for empires, a magnet for merchants, and a beacon of learning that drew seekers of knowledge from across Asia.

Though now silent, with scattered stones and weather-worn stupas, Taxila was once alive with the voices of students debating philosophy, merchants haggling in the marketplace, and monks chanting in monasteries. To step into its story is to step into a world where India, Persia, Greece, and Central Asia collided and fused.

The City at the Crossroads

Taxila’s name first appears in the Indian epics. The Ramayana identifies it as the capital of King Takṣa, son of Bharata, brother of the legendary Rama. The Mahabharata also alludes to its founding by Takṣa after the Kurukshetra war, hinting at its early sacred significance.

Geography made Taxila great. Situated on the Grand Trunk Road—an ancient highway connecting India to Central Asia and the Near East—it became a hub where caravans converged. From the Indus in the west to the Ganges plain in the east, from the passes of Bactria to the markets of Persia, all roads led through Taxila.

Shifting Empires, Shifting Loyalties

Few cities changed hands as often as Taxila. In the 6th century BCE it was absorbed into the Achaemenid Persian Empire, the easternmost satrapy of Darius I. The Behistun Inscription of Darius lists Gadāra (Gandhara, which included Taxila) among his provinces.

When Alexander the Great marched into India in 326 BCE, the city’s ruler, King Ambhi (Greek sources call him Omphis), chose diplomacy. Arrian’s Anabasis of Alexander records that Ambhi “brought elephants, silver, and eighty talents of gold” as tribute, securing Alexander’s favor. In return, Alexander rewarded him with territory once belonging to his rival Porus.

After Alexander’s successors retreated, the Mauryan Empire filled the vacuum. Chandragupta Maurya annexed Taxila around 317 BCE, and his son Bindusara later installed Ashoka as its governor. The Buddhist text Divyavadana mentions Ashoka quelling unrest in Taxila before ascending to the throne—an early glimpse of the future emperor’s political life.

Later, the Indo-Greek king Menander (Milinda), who ruled from the region in the 2nd century BCE, became a renowned patron of Buddhism. His dialogues with the monk Nagasena are preserved in the Milindapanha, which describes him as a wise ruler who questioned, debated, and eventually accepted Buddhist philosophy.

By the 1st–3rd centuries CE, the Kushans controlled Taxila, integrating it into the vast trade networks of the Silk Road.

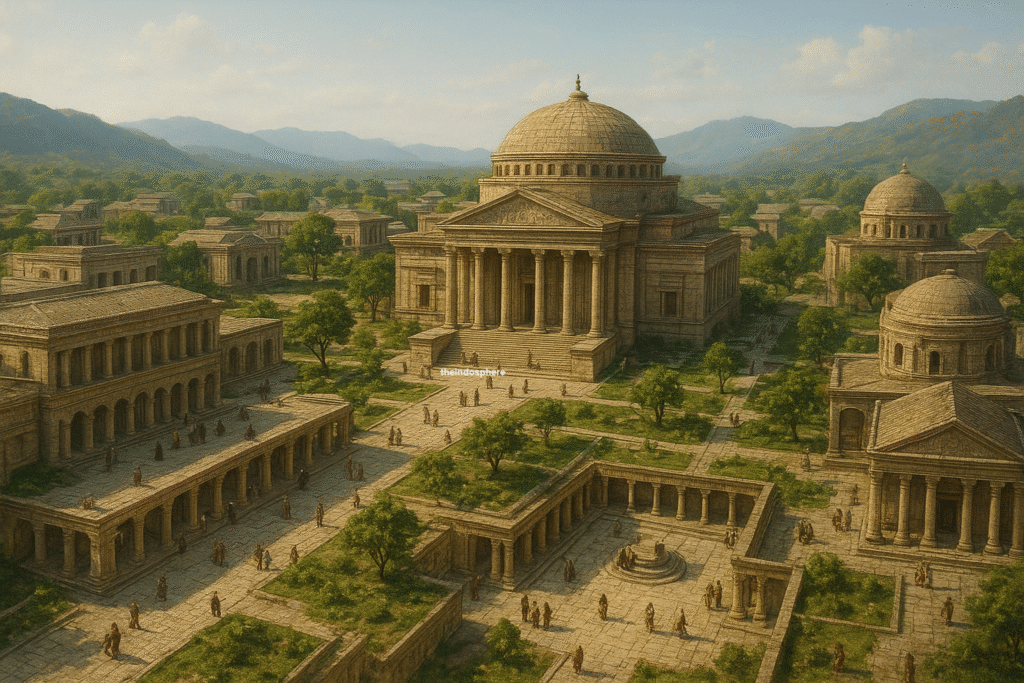

A City of Scholars

Taxila’s greatest renown lay in its role as a center of learning. The “University of Taxila” was not a university in the modern sense but a constellation of teachers and institutions. Students often traveled long distances to study there. The Jātakas (Buddhist birth stories) repeatedly mention young men being sent to Taxila for advanced training in subjects ranging from medicine to warfare.

The Mahābhārata itself recalls that princes were educated at Taxila, learning archery, statecraft, and the Vedas.

Notable figures linked to Taxila include:

- Panini (4th c. BCE): The grammarian whose Aṣṭādhyāyī revolutionized the study of Sanskrit. His precision influenced not only linguistics but also logic and mathematics.

- Chanakya (Kautilya): The mastermind behind the Mauryan Empire and author of the Arthashastra. Tradition holds he studied and taught at Taxila, shaping political theory with realism and strategy.

- Jivaka: The personal physician of the Buddha, trained in Taxila, is celebrated in the Pali Canon for his surgical skill and medical knowledge.

The subjects of study included the Vedas, Buddhist scriptures, philosophy, grammar, mathematics, medicine, astronomy, and military sciences. Entry was selective, often requiring both aptitude and patronage.

Faith and Philosophy

Taxila was a crucible of religions. Under the Mauryans and Kushans, Buddhism flourished. The great Dharmarajika stupa, attributed to Ashoka, became a pilgrimage center. The Chinese pilgrim Faxian (early 5th century CE) described Taxila as filled with Buddhist monasteries and stupas, though already beginning to decline. Xuanzang (7th century CE), visiting two centuries later, found much in ruins, yet noted the lingering presence of monasteries.

Hinduism, too, remained integral. The Dharmashastras and Vedic education thrived in its schools. Jain traditions mention teachers traveling to Taxila, while Greek influence gave rise to hybrid forms of art and thought. Gandharan sculptures, combining Indian religious themes with Greco-Roman realism, remain some of the most striking artifacts from Taxila.

Decline and Silence

By the 5th century CE, the city’s fortunes waned. The White Huns (Hephthalites) invaded, burning monasteries and destroying urban life. Xuanzang later mourned that the once-glorious seat of learning lay deserted. Trade shifted eastward, and new centers like Nalanda in Bihar took up the mantle of Buddhist scholarship.

Rediscovery and Legacy

For centuries Taxila was forgotten, mentioned only in scattered texts. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Sir John Marshall and his team excavated its layered ruins. They uncovered Bhir Mound, Sirkap, and Sirsukh—revealing a city that was never static but continually reinvented under successive empires.

Today, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Taxila stands as a reminder of how knowledge and culture thrived at the crossroads of civilizations. It was a place where Sanskrit grammar, Greek art, Buddhist philosophy, and Persian administration coexisted—proof that history’s richest chapters are written not in isolation, but in exchange.