1. Introduction

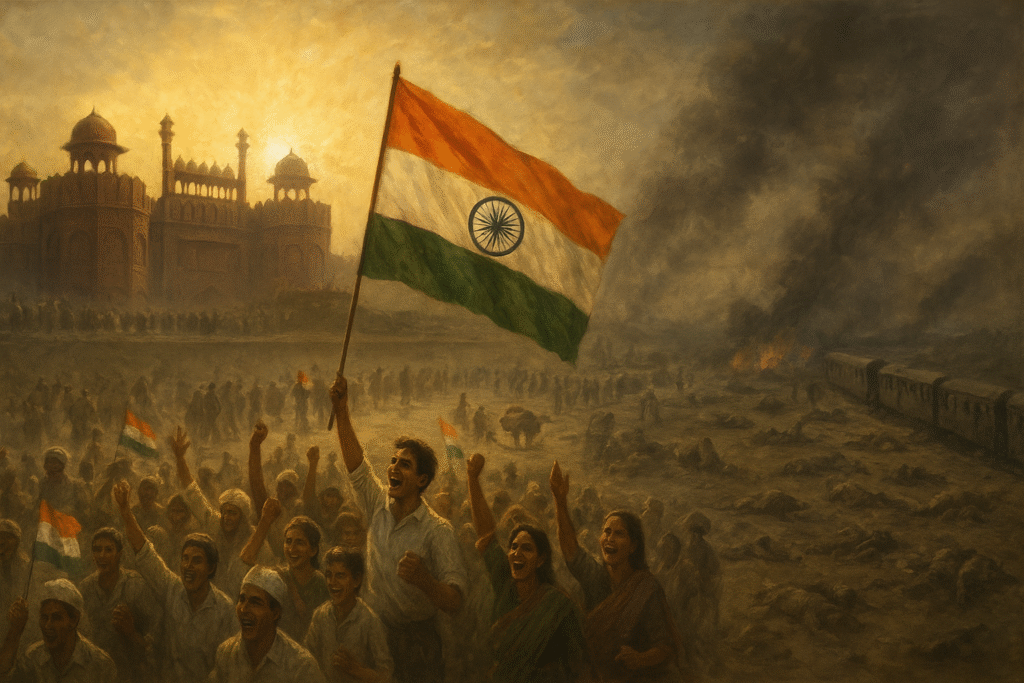

The Partition of India in 1947 was one of the most significant and traumatic events in the modern history of South Asia. It marked the end of nearly two centuries of British colonial rule and the birth of two sovereign nations — India and Pakistan. While it represented a political victory for nationalist movements that had long fought for independence, it also unleashed one of the largest and bloodiest forced migrations in human history.

Within months, an estimated 14 to 15 million people were uprooted from their homes, crossing hastily drawn borders to join the country aligned with their religion. Hindus and Sikhs fled Pakistan for India, while Muslims moved from India into Pakistan. The human cost was catastrophic: between 500,000 and two million people were killed, millions more injured, and countless families shattered.

Partition was not a sudden rupture but the culmination of decades of political, religious, and social divisions — many of which were intensified under colonial rule. Understanding its causes and consequences requires examining the intertwined history of British imperial policy, nationalist demands, communal politics, and the geopolitical pressures of the mid-20th century.

2. Historical Background

2.1 British Colonial Rule in India

The British East India Company gradually expanded its influence in the Indian subcontinent from the 18th century, gaining control through a mix of military conquest, diplomacy, and alliances with local rulers. By 1858, following the revolt of 1857, the British Crown assumed direct control, marking the formal beginning of the British Raj.

Colonial rule brought significant economic, social, and political changes. The British introduced modern administrative systems, legal codes, railways, and telegraph lines, but these developments often served imperial interests rather than local needs. Economic policies reoriented India’s economy toward supplying raw materials to Britain and importing manufactured goods, disrupting traditional industries and livelihoods.

The Raj also transformed Indian society through new educational institutions and political structures. While English-language education created a class of Indians familiar with Western ideas, it also fostered political awareness and demands for self-rule.

2.2 Rise of Nationalist Movements

By the late 19th century, opposition to colonial rule had begun to take organized form. The Indian National Congress (INC), founded in 1885, initially sought greater Indian participation in governance but gradually shifted toward the goal of full independence. Leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, and Annie Besant championed swaraj (self-rule).

Parallel to the INC, Muslim political consciousness was also growing. The All-India Muslim League, founded in 1906, emerged partly in response to fears that a Hindu-majority Congress would dominate a future independent India. While early Muslim League leaders sought cooperation with Congress, political divisions deepened over time.

2.3 Communal Tensions in Colonial India

British policies often deepened religious divisions. The colonial administration implemented separate electorates for Muslims under the Morley-Minto Reforms (1909), institutionalizing political representation along communal lines. While framed as a safeguard for minority rights, this system reinforced religious identities as the primary basis for political organization.

Communal tensions periodically flared into violence, as in the Hindu–Muslim riots of the 1920s and 1930s. These incidents planted seeds of distrust that political leaders later struggled to overcome.

3. The Demand for Pakistan

3.1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the Two-Nation Theory

By the 1930s, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, once a Congress ally, had become the foremost leader of the Muslim League. Jinnah argued that Hindus and Muslims were distinct nations with their own religions, cultures, and social practices, making coexistence in a single state problematic. This view came to be known as the Two-Nation Theory.

3.2 The Lahore Resolution (1940)

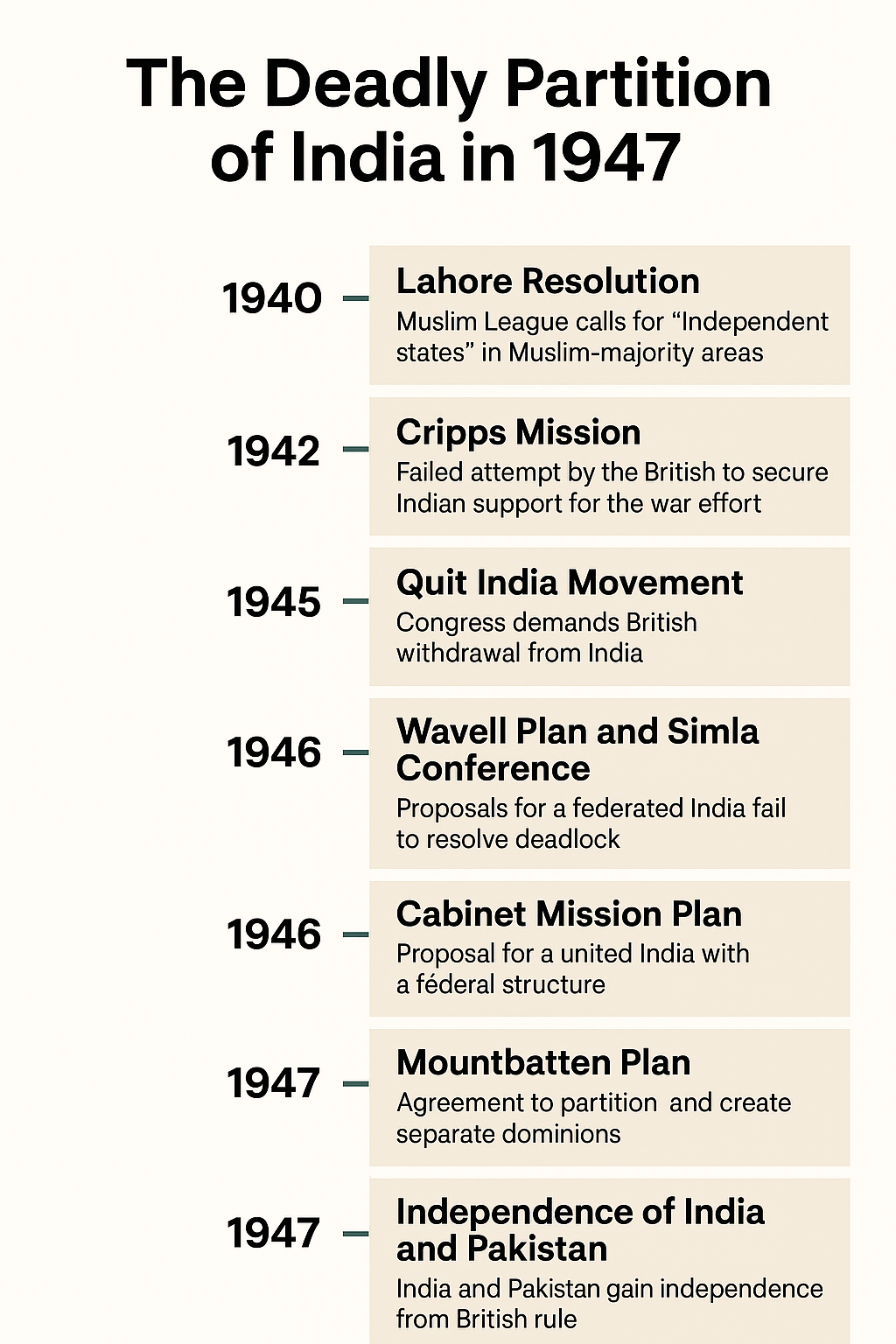

At the Muslim League’s annual session in Lahore in March 1940, the party passed a resolution calling for “independent states” in the Muslim-majority areas of northwestern and eastern India. Although the resolution was somewhat vague, it is widely interpreted as the formal articulation of the demand for Pakistan.

3.3 Political Negotiations in the 1940s

During the 1940s, negotiations between Congress, the Muslim League, and the British government repeatedly broke down over the question of Muslim political safeguards and the future structure of governance. The League increasingly insisted on a separate homeland for Muslims, while Congress leaders maintained that India should remain united but with constitutional protections for minorities.

4. The Road to Partition

4.1 The Cripps Mission (1942)

In 1942, the British government sent Sir Stafford Cripps to negotiate Indian support for the war effort in exchange for a post-war promise of dominion status. The mission failed, as Congress demanded immediate independence and the Muslim League rejected the proposals for insufficiently guaranteeing Muslim autonomy.

4.2 The Quit India Movement

Frustrated by the lack of progress, Congress launched the Quit India Movement in August 1942, calling for the British to leave India immediately. The movement was suppressed with mass arrests, weakening Congress’s position during the war years.

4.3 Wavell Plan and Simla Conference (1945)

The Wavell Plan proposed reconstituting the Viceroy’s Executive Council to include more Indian leaders, but disagreements over Muslim representation stalled progress. The Simla Conference of 1945 ended in deadlock, deepening the political divide.

4.4 The Cabinet Mission Plan (1946)

In early 1946, the Cabinet Mission from Britain proposed a united India with a federal structure. The plan grouped provinces into clusters, with autonomy over internal matters. Initially accepted by both Congress and the League, it soon collapsed over disagreements about the powers of the central government.

4.5 Direct Action Day

On August 16, 1946, the Muslim League called for Direct Action to demand Pakistan. In Calcutta, this led to large-scale communal violence known as the Great Calcutta Killings, leaving thousands dead. The violence spread to other regions, making reconciliation increasingly unlikely.

4.6 Mountbatten Plan (June 3, 1947)

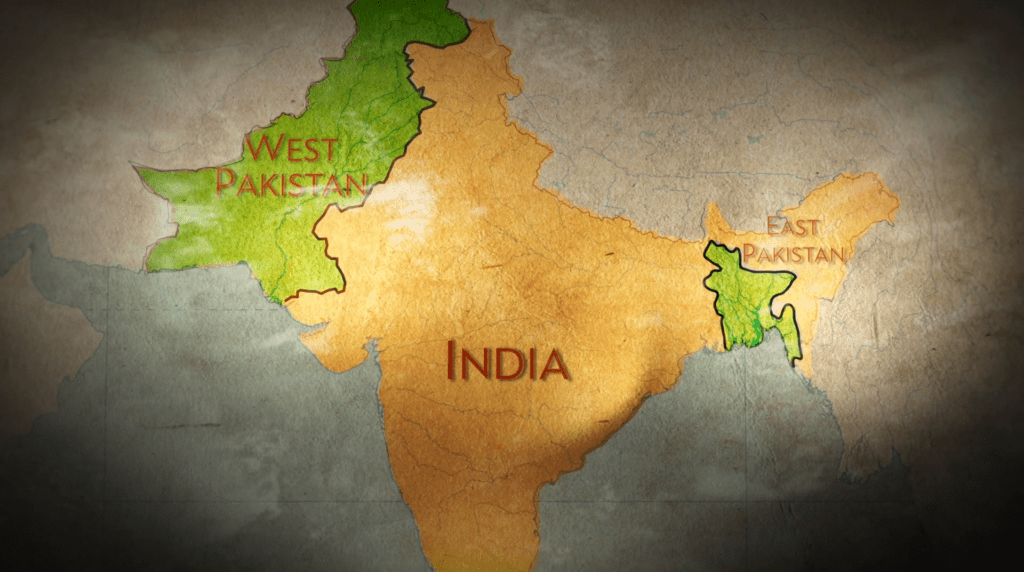

When Lord Louis Mountbatten became the last Viceroy in March 1947, he concluded that partition was unavoidable. The Mountbatten Plan proposed creating two dominions — India and Pakistan — with partition of Punjab and Bengal. Both Congress and the League agreed, and the British Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act in July 1947.

5. The Decision and the Radcliffe Line

5.1 Appointment of Cyril Radcliffe

To draw the new boundaries, the British appointed Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a barrister with no prior experience in India. He was given just five weeks to demarcate the borders between India and Pakistan in Punjab and Bengal.

5.2 Criteria for Boundary Demarcation

Radcliffe’s commissions considered religious demographics, economic resources, and transport networks. However, the speed of the process and incomplete data meant that many decisions were contentious.

5.3 Announcement of Independence

On August 14, 1947, Pakistan was declared independent, followed by India on August 15. The Radcliffe Award, which detailed the boundaries, was announced only on August 17, after independence — by which time large-scale migration and violence had already begun.

6. Mass Migration and Violence

6.1 Scale of Migration

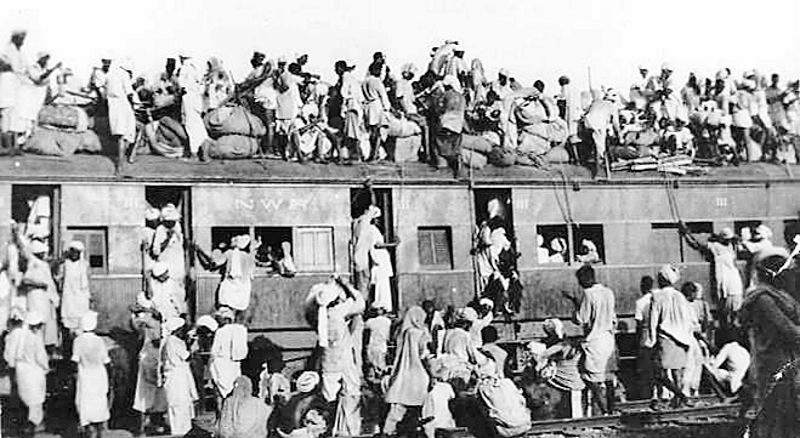

Partition triggered the movement of approximately 14 to 15 million people, making it the largest mass migration in recorded history outside wartime. Entire communities left their ancestral homes, often with only what they could carry.

6.2 Violence in Punjab

Punjab witnessed the worst violence. Armed militias attacked refugee convoys, villages were burned, and trains carrying refugees were ambushed. Mass killings were accompanied by abductions and assaults on women.

6.3 Violence in Bengal and Other Regions

Bengal saw significant bloodshed in Calcutta, Noakhali, and other districts. Communal riots also occurred in Delhi and other urban centers, where refugee influxes altered demographics overnight.

6.4 Targeting of Women

Women were subjected to abduction, rape, and forced conversion. Many were never reunited with their families. The trauma endured by women became one of the most tragic and less-discussed aspects of Partition.

7. Humanitarian Crisis

Both India and Pakistan established makeshift refugee camps. Conditions were overcrowded, sanitation poor, and food scarce. Disease outbreaks were common. Governments, charities, and international organizations struggled to provide relief. The sheer number of displaced people overwhelmed available resources. Many refugees lost all property and sources of income. Resettlement often meant starting life anew in unfamiliar regions.

8. Political Aftermath

India adopted a secular constitution, while Pakistan was founded as a homeland for Muslims, though debates about the role of religion in the state persisted from the start. Partition left the princely states to choose between India and Pakistan. Kashmir’s decision to accede to India in 1947 sparked the first Indo–Pakistan war, a conflict that remains unresolved. Partition sowed seeds of mistrust between the two nations. Subsequent wars (1965, 1971, and 1999) and ongoing border disputes can be traced back to 1947.

9. Long-Term Impact

Communities that had coexisted for centuries were separated. Cultural exchange between India and Pakistan diminished, and shared heritage sites became contested symbols. Partition hardened religious identities in both countries. Minorities often faced discrimination, and memories of 1947 influenced later communal conflicts. Historians and political leaders have studied Partition to understand how political negotiation failures, identity politics, and rushed decisions can lead to humanitarian disasters.

The Partition of India in 1947 was not just the division of territory but the rupture of human lives on an unprecedented scale. It ended colonial rule but left deep wounds that still shape South Asian politics, society, and memory. While historians debate whether Partition was inevitable, its human cost remains a stark reminder of the dangers of dividing nations along communal lines.