High on the spine of Asia lies a land of mountains, windswept plateaus, sacred lakes, and monasteries clinging to cliffsides. This is Tibet, often called “the Roof of the World,” a phrase that captures both its physical elevation and its place in human imagination. For millennia, Tibet has fascinated outsiders—travelers, conquerors, pilgrims, and scholars alike. Yet to understand Tibet is not simply to look at its mountains and monasteries, but to trace the deep currents of history that shaped a unique civilization.

This essay explores Tibet in full, from its prehistoric beginnings through the rise of the Tibetan Empire, the enduring traditions of Buddhism and Bön, the emergence of the Dalai Lama system, encounters with foreign powers, and its contested modern status. It is a journey into a land that is at once remote and deeply connected to the currents of world history.

Prehistoric Tibet: Life on the World’s Highest Plateau

Long before Tibet became a kingdom or even a cultural idea, people lived on its vast plateau. Archaeological discoveries suggest that humans have occupied parts of Tibet for at least thirty thousand years. Stone tools found in caves and open-air sites testify to the endurance of early hunter-gatherers who braved the thin air and icy winds. Unlike other cradles of civilization—fertile valleys like the Nile or Mesopotamia—Tibet offered no easy path. Life here required adaptation of a rare kind.

By the Neolithic period, around the third millennium BCE, Tibetans had begun to cultivate barley, a crop hardy enough to survive the cold and high altitude. They also domesticated the yak, an animal without which Tibetan life would be unimaginable. The yak provided milk, butter, wool, hides, and meat, but it was also a beast of burden, carrying loads across mountain passes and serving as the foundation of trade networks. To this day, Tibetans sometimes say that their entire civilization rests upon the back of the yak.

Genetic studies of modern Tibetans reveal remarkable biological adaptations to high-altitude life. Unlike most populations, Tibetans can thrive with lower hemoglobin levels, reducing the risk of blood thickening in oxygen-poor environments. This adaptation is thought to have developed thousands of years ago, enabling humans not only to survive but to settle permanently in a region where few outsiders could endure long-term.

The Zhang Zhung Kingdom and the World of Bön

While scattered communities thrived across the plateau, western Tibet nurtured one of the earliest organized states: the kingdom of Zhang Zhung. Centered around the holy Mount Kailash and Lake Manasarovar, Zhang Zhung was a civilization that flourished long before the rise of the Tibetan Empire.

The Zhang Zhung people spoke their own language, distinct from Tibetan, and developed a script. Fragments of that script survive in later Tibetan texts, though much of it is lost. They divided their realm into three spheres: the inner, middle, and outer regions, with Mount Kailash considered the cosmic and political center.

Equally important was their spiritual system: the Bön religion. Bön was a complex blend of shamanism, animism, and ritual practice. It taught reverence for mountain gods, lake spirits, and protective deities, while priests performed ceremonies for healing, exorcism, and prosperity. In Bön cosmology, the universe was populated by gods and demons, and the human world was constantly in need of ritual mediation.

Later Buddhist chronicles, written from the perspective of Buddhism’s triumph, often depicted Bön as crude or even demonic. Yet historical evidence shows that Bön was sophisticated, with its own scriptures, philosophical ideas, and monastic traditions. When Buddhism eventually spread in Tibet, it did not erase Bön but absorbed many of its rituals, deities, and cosmological concepts. The legacy of Zhang Zhung and Bön thus lived on, shaping Tibetan identity even after the kingdom itself was conquered.

The Yarlung Valley and the Birth of Tibetan Kingship

While Zhang Zhung held sway in the west, central Tibet was home to numerous clans and tribes. The Yarlung Valley, located south of modern Lhasa, became the cradle of Tibetan statehood. According to Tibetan legend, the earliest kings descended from the sky, climbing down a heavenly rope to rule the land. For generations, these kings were said to return to heaven upon death, leaving no bodies behind. Only later did they begin to die like ordinary humans, requiring burial mounds, some of which still stand in the Yarlung Valley today.

These stories mix myth and memory, but they point to the sacred aura that surrounded early Tibetan kingship. The ruler was not just a political leader but a mediator between the human and divine realms. Over time, Yarlung chieftains consolidated their authority, subduing rival clans and forging alliances. By the early seventh century, a leader named Namri Songtsen had extended Yarlung influence over much of central Tibet. His son, Songtsen Gampo, would go further still, founding what we can call the first Tibetan state.

The Rise of the Tibetan Empire

Songtsen Gampo, who ruled from around 618 to 650 CE, is remembered as the founder of the Tibetan Empire. He expanded his father’s conquests, subduing the Zhang Zhung kingdom and unifying central Tibet under his rule. His capital, Lhasa, became not only a political center but also a spiritual one.

Songtsen Gampo’s reign is associated above all with the introduction of Buddhism. He married Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal and Princess Wencheng of China’s Tang dynasty, both devout Buddhists, and through these unions Tibet received its first Buddhist images and texts. Legends say that each princess brought a sacred statue to Tibet, one of which, the Jowo Shakyamuni, remains enshrined in the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa.

The king also commissioned the creation of a Tibetan script, modeled on Indian alphabets. This was a revolutionary step, for it allowed Buddhist scriptures to be translated and a written historical record to be kept. Literacy and literature became tools of statecraft, cementing Tibet’s place in the broader intellectual world of Asia.

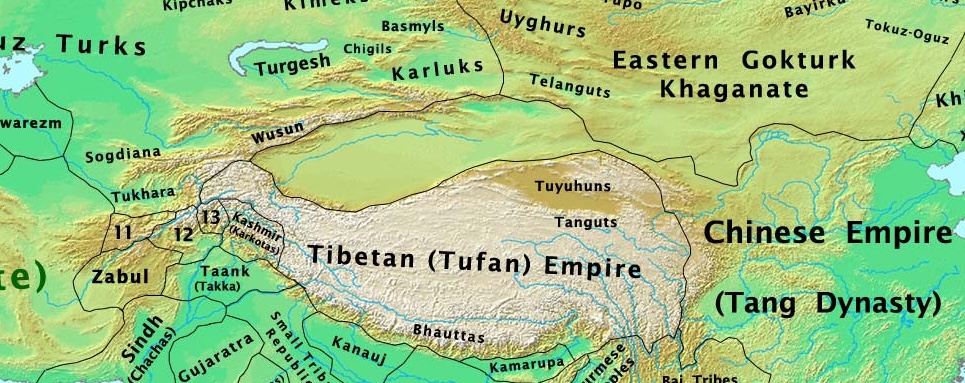

Within a century, Tibet grew into one of the great empires of Inner Asia. Its armies clashed with the Tang dynasty of China, sometimes even threatening the Tang capital of Chang’an. At its height in the eighth and ninth centuries, the Tibetan Empire stretched from Central Asia to the Himalayas, controlling trade routes and commanding respect from neighboring states.

The Spread of Buddhism and the Transformation of Culture

Although introduced during Songtsen Gampo’s reign, Buddhism took several centuries to establish itself firmly. In the eighth century, the Indian scholar Shantarakshita and the tantric master Padmasambhava were invited to Tibet by King Trisong Detsen. They founded the great monastery of Samye, which became a center for translation, debate, and monastic training.

The arrival of Buddhism did not come without conflict. Followers of Bön resisted the new faith, and internal struggles marked the era. Yet Buddhism slowly took root, reshaping Tibetan culture. Monasteries became centers of learning, preserving not only Buddhist philosophy but also medicine, astrology, and the arts. Tibetan Buddhism, influenced by Indian tantric traditions, developed its own distinctive rituals, symbolism, and practices of meditation.

By the ninth century, Tibet was recognized not just as a military power but as a spiritual one. Yet the empire was fragile. Internal divisions and dynastic struggles weakened it, and in the mid-ninth century, after the assassination of King Langdarma—who had opposed Buddhism—the empire collapsed.

Tibet in the Medieval World

The fall of the empire plunged Tibet into centuries of political fragmentation. Regional warlords, monastic leaders, and aristocratic families vied for control. Yet Buddhism continued to flourish, spreading into every corner of Tibetan life. New schools of thought emerged, including the Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyu, and later the Gelug traditions, each with its own lineages and practices.

In the thirteenth century, Tibet came under the influence of the Mongol Empire. Kublai Khan, the founder of China’s Yuan dynasty, granted spiritual and political authority to the Sakya school, effectively making Tibet a protectorate. This relationship set a precedent for later interactions between Tibet and Chinese dynasties, though Tibet often maintained substantial autonomy.

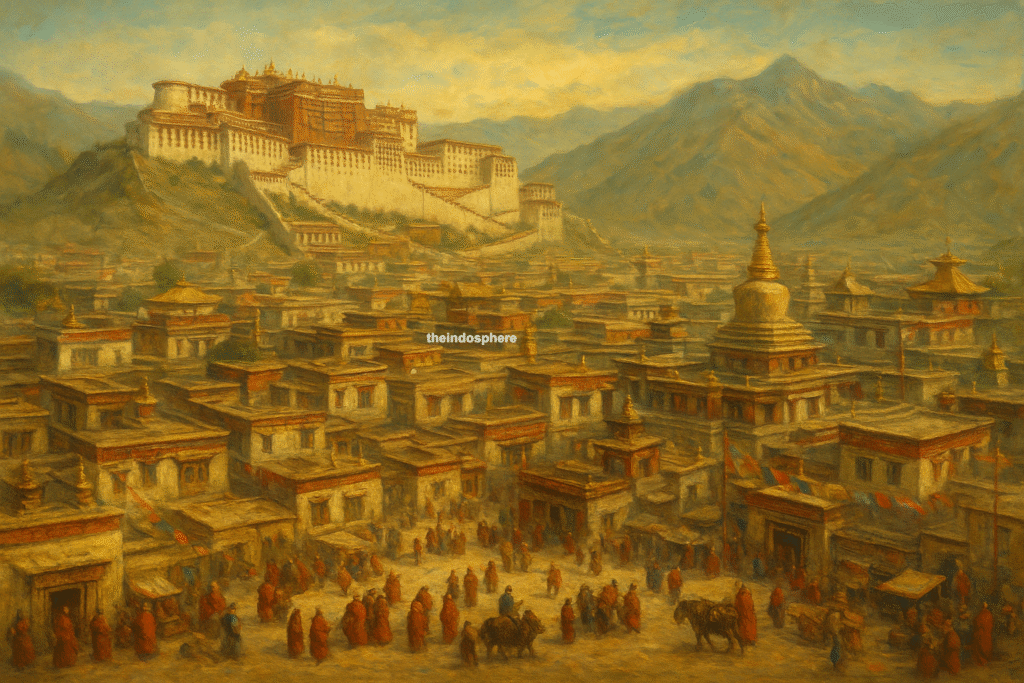

During the Ming dynasty, Tibet remained outside direct Chinese control, though diplomatic and religious exchanges continued. In the seventeenth century, the Gelug school, under the leadership of the Fifth Dalai Lama, consolidated power. Backed by Mongol patronage, the Dalai Lama established the Ganden Phodrang government in Lhasa, uniting Tibet under a theocratic system that endured for centuries.

The Dalai Lama System

The Dalai Lama institution became central to Tibetan identity. The Dalai Lama was both the supreme spiritual leader of the Gelug school and the temporal ruler of Tibet. Believed to be the reincarnation of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, the Dalai Lama embodied the union of politics and religion.

Under the Fifth Dalai Lama in the seventeenth century, Tibet entered a period of stability and cultural flowering. The Potala Palace in Lhasa, begun during his reign, stands as a monument to this era. The government combined monastic authority with aristocratic administration, while monasteries became powerful centers of learning and wealth.

This system lasted, with interruptions, until the twentieth century. It gave Tibet a distinctive form of governance, in which the spiritual and political were inseparable. To outsiders, it seemed otherworldly; to Tibetans, it was the natural order.

Encounters with Modernity

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries brought Tibet into closer contact with global powers. British India, concerned about Russian influence in Central Asia, launched the Younghusband Expedition of 1904, forcing Tibet to open trade relations. Meanwhile, China’s Qing dynasty, which had asserted some authority over Tibet since the eighteenth century, collapsed in 1911, leaving Tibet effectively independent for several decades.

In the 1950s, however, Tibet’s status changed dramatically. The newly founded People’s Republic of China asserted sovereignty over Tibet, sending troops and establishing control. In 1959, after a failed uprising in Lhasa, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama fled to India, where he established a government-in-exile. Since then, Tibet has been incorporated into China as the Tibet Autonomous Region, though debates about autonomy, cultural preservation, and human rights continue to shape its modern story.

Art, Culture, and Spiritual Life

Throughout its history, Tibet has cultivated a rich cultural heritage. Thangka paintings, intricate mandalas, and sacred sculptures express both artistic mastery and deep religious devotion. Music, dance, and opera often carry spiritual significance, while festivals like Losar, the Tibetan New Year, blend religious ritual with communal celebration.

Cuisine reflects the harsh environment: tsampa, made of roasted barley flour, remains the staple, often eaten with yak butter tea. Meat, dairy, and hardy vegetables form the backbone of the diet. Despite simplicity, food is deeply symbolic, tied to hospitality and ritual offerings.

Monasteries preserve not only religious texts but also traditional medicine, astrology, and scholarship. Tibetan medicine, with its holistic approach to the body and mind, remains influential. Even in exile, Tibetans continue to sustain these traditions, ensuring their survival beyond the plateau.

Tibet in the Modern World

Today, Tibet is undergoing rapid change. Lhasa has highways, railways, and expanding urban centers. Chinese policies have brought modernization, but also controversy over cultural preservation and religious freedom. Tourism has grown, bringing outsiders eager to experience Tibetan culture, yet political restrictions remain.

The Dalai Lama, now in exile, continues to be a global spiritual figure, advocating for nonviolence and compassion. For Tibetans inside and outside Tibet, the preservation of language, religion, and culture is a pressing concern. For the world, Tibet represents both a unique civilization and a contested political question.

Exile and the Tibetan Diaspora

The uprising of 1959 marked the beginning of Tibetan life in exile. Following China’s consolidation of control, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama fled across the Himalayas to India, where he established the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) in Dharamshala. Often called the government-in-exile, the CTA has never been formally recognized by other states but became the symbolic and administrative center for Tibetans outside their homeland.

In India, Nepal, and Bhutan, refugee settlements were built, complete with schools and monasteries. These replicated Tibet’s great monastic institutions—Drepung, Sera, and Ganden—ensuring that religion, education, and cultural traditions could survive. Over time, Tibetan communities spread further, taking root in Switzerland, the United States, Canada, and beyond. Today, roughly 150,000 Tibetans live outside Tibet, forming a global diaspora.

Exile reshaped Tibetan politics. While the government-in-exile initially pressed for independence, the Dalai Lama later proposed the Middle Way Approach, calling for genuine autonomy under Chinese sovereignty. In 2011, he stepped back from political leadership, leaving secular authority to an elected Sikyong (prime minister), a historic shift toward democracy in exile.

Paradoxically, exile amplified Tibet’s global presence. Tibetan Buddhism, carried abroad by exiled teachers and popularized by the Dalai Lama, attracted millions of followers worldwide. Tibetan art, literature, and activism found new audiences, keeping the question of Tibet alive internationally. For Tibetans themselves, the exile experience is both a story of loss and of resilience: a nation without a state that has nonetheless preserved its identity and continues to fight for its homeland.

Tibet’s Legacy

The story of Tibet is one of resilience. From prehistoric settlers braving the highest plateau on Earth, through the mysteries of Zhang Zhung and the spiritual power of Bön, to the rise of the Tibetan Empire and the flowering of Buddhism, Tibet has created a civilization both deeply rooted and globally influential. Its art, religion, and philosophy continue to inspire far beyond its borders, while its political fate remains a subject of debate.

To understand Tibet is to glimpse the interplay of geography, faith, and history at the roof of the world. It is a story of survival in harsh landscapes, of profound spiritual vision, and of a people who, despite centuries of change, continue to shape and redefine their place in the modern world.

Bibliography

General Histories of Tibet

- Beckwith, Christopher I. The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press, 1987.

- Powers, John. History as Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles versus the People’s Republic of China. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. Tibet: A Political History. Yale University Press, 1967.

- Samuel, Geoffrey. Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.

Archaeology and Prehistoric Tibet

- Aldenderfer, Mark, and Zhang, Y. “The Prehistory of the Tibetan Plateau to the Seventh Century A.D.: Perspectives and Research from China and the West Since 1950.” Journal of World Prehistory 18, no. 1 (2004): 1–55.

- Meyer, Fernand, and Guntram Hazod. Tibet’s Ancient Kingdom of Zhang Zhung: Texts and Traditions. Serindia Publications, 2003.

Religion and Philosophy

- Snellgrove, David L. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors. Shambhala, 1987.

- Kvaerne, Per. The Bon Religion of Tibet: The Iconography of a Living Tradition. Serindia Publications, 1995.

- Lopez, Donald S. Jr., ed. Religions of Tibet in Practice. Princeton University Press, 1997.

- Kapstein, Matthew. The Tibetans. Wiley-Blackwell, 2006.

Dalai Lama Institution and Tibetan Governance

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. University of California Press, 1989.

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama. University of California Press, 1997.

- Shakya, Tsering. The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947. Penguin, 1999.

Art, Culture, and Society

- Rhie, Marylin M., and Robert A. F. Thurman. Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet. Abrams, 1991.

- Tucci, Giuseppe. Tibetan Painted Scrolls. 3 vols., Roma: Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1949.

- Jackson, David. The Nepalese Legacy in Tibetan Painting. Marg Publications, 2010.

Modern Tibet and Politics

- Barnett, Robert. Lhasa: Streets with Memories. Columbia University Press, 2006.

- Sperling, Elliot. The Tibet-China Conflict: History and Polemics. East-West Center, 2004.

- van Walt van Praag, Michael. The Status of Tibet: History, Rights, and Prospects in International Law. Westview Press, 1987.

Articles and Essays

- Schwartz, Ronald D. “Circle of Protest: Political Ritual in the Tibetan Uprising.” Modern China 12, no. 4 (1986): 425–460.

- Childs, Geoff. “Culture, Ecology, and Demography: Reflections on the Sustainability of Tibetan Populations in Nepal.” Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies 22, no. 1 (2002): 1–18.

- Yeh, Emily T. “Tibetan Indigeneity: Translations, Resemblances, and Uncanny Translations.” Cultural Anthropology 22, no. 4 (2007): 589–620.