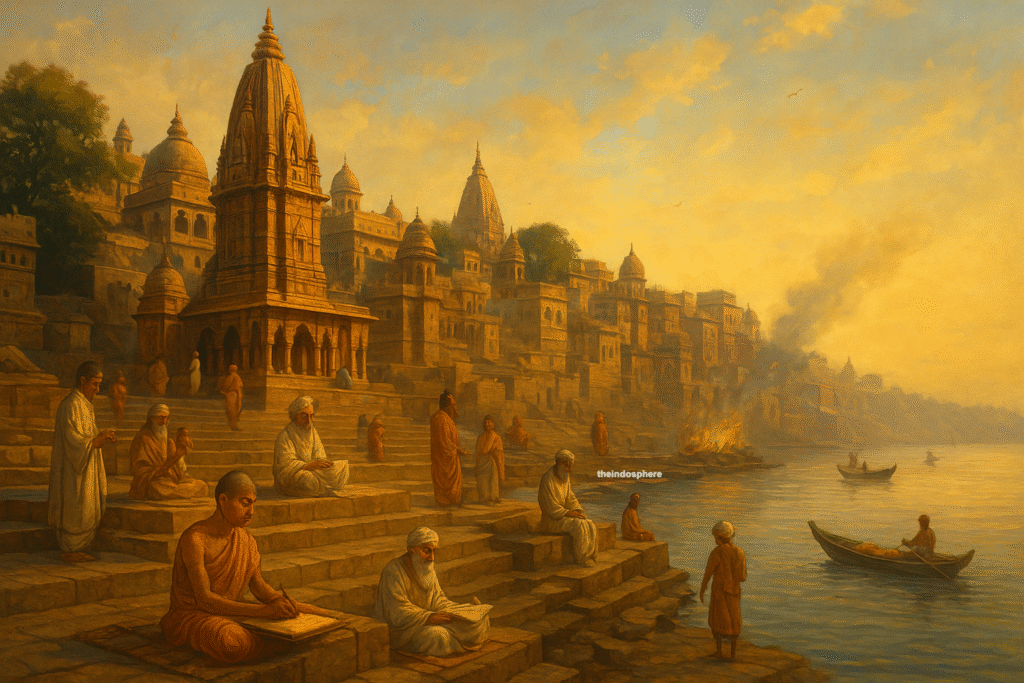

On the banks of the Ganga, where the river bends gently northward, lies Varanasi—the city the ancients called Kashi, “the Luminous One.” Few places on earth have been so continuously inhabited, or so richly layered with myth, memory, and meaning. For Hindus, it is the holiest of cities; for Buddhists and Jains, it is equally sacred; for poets, philosophers, and travelers, it has long been a source of wonder.

The Atharva Veda speaks of Kashi as a shining city, a “beacon of learning and devotion.” The Skanda Purāṇa calls it the city of Shiva himself, where liberation is nearest. To this day, pilgrims believe that dying in Varanasi, or even having one’s ashes immersed in the Ganga here, guarantees moksha, release from the cycle of rebirth.

The Mythic City

Varanasi’s sacred geography is bound to myth. According to Hindu tradition, the city was founded by Shiva, who made it his eternal abode after marrying Parvati. The Kashi Khanda of the Skanda Purāṇa describes the city as existing “before creation itself,” beyond the reach of time.

Jain texts record that Parshvanatha, the 23rd Tirthankara, was born here in the 9th century BCE. For Buddhists, the nearby Deer Park at Sarnath is where the Buddha preached his first sermon after enlightenment, setting in motion the Dharma Chakra. Thus, the city stands at the confluence of three great traditions.

Early History

Varanasi’s antiquity is staggering. Archaeological evidence suggests continuous settlement from the 2nd millennium BCE, making it one of the oldest living cities in the world. By the 6th century BCE, when the Buddhist Jātakas were being composed, Kashi was already a renowned Mahājanapada (great kingdom). The Jātakas mention Kashi as a center of trade, with fine textiles and crafts.

In the Mahābhārata, the city appears repeatedly as a site of pilgrimage. The text praises its temples and ghats, underscoring its already-established sanctity.

By the time the Buddha walked its streets, Varanasi was not only a sacred city but a thriving urban hub, with artisans, scholars, and merchants filling its alleys.

A City of Trade and Craft

For much of antiquity, Varanasi’s fame rested on its textiles. The Rigveda refers to Kashi kauseya (silk from Kashi), and by later centuries, its muslin and silk weaving were prized across Asia. Greek and Chinese travelers alike remarked on the quality of its cloth.

Its location on the Ganga also made it a commercial artery. Caravans from the north brought horses, wool, and gems; traders from the east carried rice and spices; goods from the Deccan traveled northward by river.

Seat of Learning

Like Taxila and Ujjain, Varanasi was a center of intellectual life, though with a different flavor. Here, knowledge was deeply entwined with religion.

- Vedic Learning: Varanasi was one of the chief sites where the Vedas were studied and recited. The city became synonymous with Sanskrit scholarship and ritual expertise.

- Philosophy: For centuries, Varanasi was a cradle of Hindu philosophical schools. Advaita Vedanta, Nyaya, and Mimamsa thinkers taught here. In the medieval period, the philosopher Madhusudana Sarasvati composed major works in Varanasi.

- Buddhist and Jain Influence: Although Sarnath became the principal Buddhist center, monks and pilgrims from across Asia passed through Varanasi. Jain traditions also rooted themselves here through Parshvanatha’s legacy.

The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang (7th c. CE) visited and described it as a city “with many temples and flourishing in learning.”

Faith and Ritual

Religion has always been Varanasi’s soul. The Kashi Vishwanath Temple, dedicated to Shiva, has been the city’s spiritual heart for centuries, rebuilt many times after invasions and destruction. Pilgrims stream daily to its shrine, believing that a glimpse of the Jyotirlinga grants liberation.

The ghats—stone steps leading to the river—are central to Varanasi’s identity. The Manikarnika Ghat is where cremations take place, day and night, for it is believed that fire from Shiva himself burns here, never extinguished. The Dashashwamedh Ghat, where Brahma is said to have performed ten horse sacrifices, remains the ceremonial center of the city.

Festivals transform Varanasi into a cosmic theater. The Ganga Aarti at sunset, the Dev Deepawali in Kartik month, and the Mahashivaratri processions continue traditions described in Purāṇic texts.

The City Through Empires

Varanasi survived conquest after conquest. Under the Mauryas, especially Ashoka, Buddhism flourished nearby at Sarnath. In the Gupta period, the city remained a religious and cultural capital.

During the medieval era, it suffered repeated sackings—by Mahmud of Ghazni in the 11th century, and later by Aurangzeb, who built the Gyanvapi mosque atop the destroyed Vishwanath temple. Yet the city always revived, its sanctity indestructible.

In the 18th century, under the patronage of the Marathas and later the Benares kings, temples were rebuilt. Pilgrimage activity surged again, and scholars continued to make Varanasi a center of Sanskrit learning.

Colonial and Modern Varanasi

When the British arrived, they too were struck by the city’s timeless aura. James Prinsep, who worked in Benares in the 1820s, documented its architecture and inscriptions while also devising the system to decipher the Brahmi script.

In the 20th century, Mahatma Gandhi chose Benares as the site of one of his early public addresses in 1916, at the inauguration of Banaras Hindu University (founded by Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya). The university cemented Varanasi’s place as a modern seat of learning while honoring its ancient role.

The Eternal City

Mark Twain, who visited in 1896, famously remarked: “Benares is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together.”

Today, Varanasi is at once ancient and modern—its lanes echo with temple bells and the chants of priests, while weavers craft silks that find their way to global markets. The Ganga still flows past ghats where life, death, and rebirth converge daily in ritual.

Unlike Taxila, which fell silent, or Ujjain, which waxed and waned, Varanasi never ceased. It has remained continuously alive, continuously sacred. If Ujjain was the cosmic clock and Taxila the intellectual crossroads, then Varanasi is the soul of India itself—eternal, luminous, and inexhaustible.