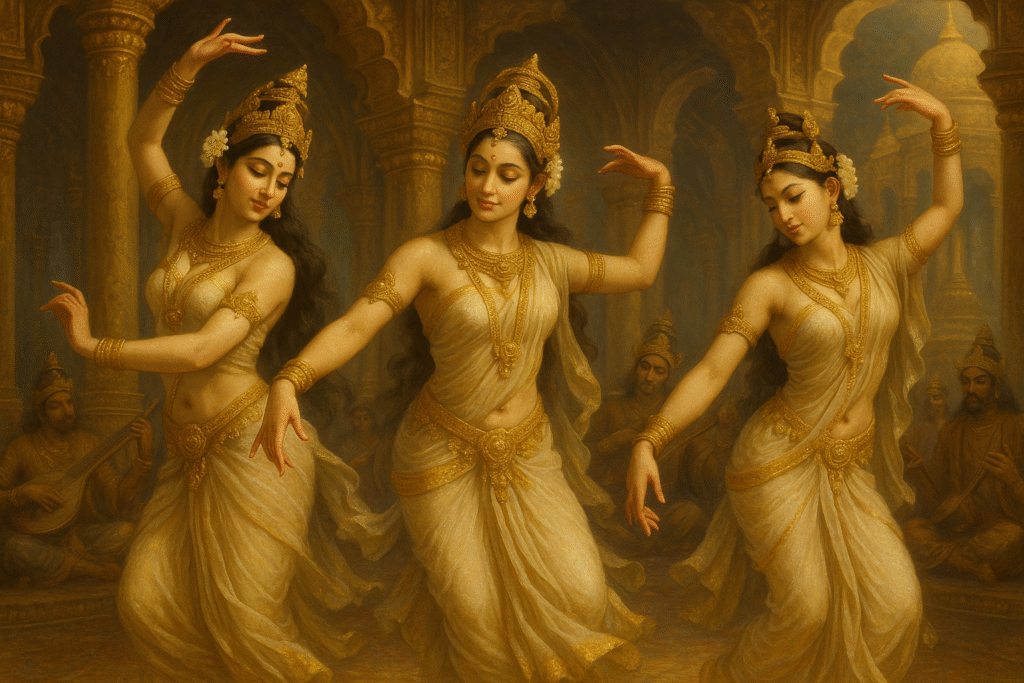

In the mythological traditions of South Asia, few figures embody divine allure and artistic perfection like the Apsaras. Often described as celestial dancers and courtesans of the gods, Apsaras appear throughout Hindu and Buddhist texts as embodiments of beauty, movement, and seduction. But their role is more than ornamental—they are symbols of the subtle, persuasive power of emotion, art, and desire in both divine and mortal realms.

This article offers a detailed look at who the Apsaras are, their origins, their roles in mythology, and their symbolic significance.

1. Who Are the Apsaras?

Apsaras are female celestial beings known for their extraordinary beauty, grace, and skill in dance and music. In Hindu and Buddhist cosmologies, they serve in the courts of gods—especially Indra, king of the heavens—and are often seen performing during battles, rituals, or divine celebrations.

They are commonly paired with their male counterparts, the Gandharvas, the celestial musicians. While the Gandharvas create sound, the Apsaras embody movement. Together, they represent the divine fusion of music and dance, form and rhythm, emotion and experience.

2. Origins and Etymology

The term Apsara is derived from the Sanskrit root aps (water) and ri (to move or go), implying a being that moves in or comes from water. This etymology hints at their fluid, seductive, and elusive nature.

Creation Stories

- In Hindu mythology, Apsaras are said to have emerged from the ocean during the Samudra Manthan, the churning of the cosmic ocean—a moment that also produced other divine beings and objects.

- Some texts describe them as creations of Brahma, meant to serve the gods by entertaining them and maintaining harmony through the arts.

3. Appearance and Attributes

Apsaras are universally described as:

- Stunningly beautiful women, radiant and youthful.

- Graceful dancers with fluid, mesmerizing movements.

- Clothed in silks and adorned with jewelry, often depicted with garlands and flowing scarves.

- Skilled in music, poetry, and seduction.

Their physical appearance, though emphasized, is secondary to their symbolic role: they represent emotional depth, beauty in motion, and the power of attraction.

4. Roles in Mythology

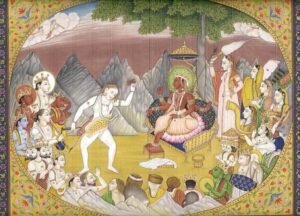

4.1. Dancers of Heaven

Apsaras perform in the court of Indra, entertaining gods and warriors with their dances. Their performances are not merely aesthetic; they are sacred acts that honor divine events, bless victories, and stabilize cosmic order.

4.2. Instruments of Distraction

In many stories, Apsaras are sent to disrupt penance or test the resolve of sages. Their beauty and charm are used as divine tools to prevent ascetics from gaining dangerous levels of power through austerities. Famous examples include:

- Menaka, who seduced the sage Vishvamitra.

- Rambha, sent to tempt sage Vishwamitra again, and later cursed for it.

- Urvashi, who captivated King Pururavas in one of the most famous celestial love stories.

4.3. Participants in Human Affairs

Apsaras occasionally fall in love with mortals and descend to earth, sometimes marrying kings or heroes. However, these unions are often temporary, with the Apsaras eventually returning to the celestial realm—symbolizing the tension between desire and detachment, spirit and matter.

5. Types and Notable Apsaras

Hindu texts mention numerous Apsaras—each with distinct qualities, stories, or roles. Some of the most notable include:

| Name | Known For |

|---|---|

| Menaka | Sent to seduce sage Vishvamitra; mother of Shakuntala. |

| Rambha | Often involved in mythological love stories and conflicts. |

| Urvashi | A powerful Apsara who fell in love with a mortal king. |

| Tilottama | Created from the essence of all beauty to distract demons. |

| Ghritachi | Mother of many important sages and heroes in various stories. |

In the Natya Shastra (ancient treatise on performing arts), Apsaras are considered archetypes of perfect dance, and many classical Indian dance traditions draw on their imagery and movement styles.

6. Apsaras in Buddhism

In Buddhist cosmology, Apsaras also appear as celestial dancers who inhabit the Trayastrimsha heaven, serving the devas. Though less personalized than in Hinduism, their role remains consistent: attendants of beauty, music, and delight in the heavenly realms.

Their existence supports the idea that even in Buddhist thought, sensory experience has a place within the cosmic hierarchy—though it is ultimately transient and not the goal of liberation.

7. Symbolism and Interpretation

Apsaras are rich in metaphor and cultural meaning. They represent:

- The power of beauty: not just to attract, but to inspire and elevate.

- The impermanence of pleasure: their love affairs with mortals never last.

- Emotional and artistic expression: they are not warriors or sages, but their influence can be just as profound.

- The divine feminine: graceful, persuasive, independent, and often morally complex.

Their stories invite reflection on desire, distraction, and discipline—especially in the context of spiritual practice. They are reminders that the path to enlightenment passes not only through renunciation but also through understanding and integrating the full range of human emotion.

8. Legacy and Modern Depictions

Today, Apsaras continue to influence:

- Classical Indian dance—especially in Bharatanatyam, Odissi, and Kathak, where many poses and themes are drawn from their myths.

- Temple sculpture and painting—especially in Khajuraho, Konark, and the Ajanta caves.

- Southeast Asian art, particularly in Khmer and Balinese traditions, where Apsaras appear as “Devatas” or celestial nymphs.

In contemporary culture, they are often invoked in literature, theatre, film, and fashion as symbols of feminine power, grace, and divine beauty.

Apsaras are more than mythical dancers. They are integral to a worldview where beauty, motion, and emotion are not superficial, but deeply tied to spiritual meaning. Whether as symbols of desire, agents of cosmic balance, or archetypes of artistic perfection, Apsaras continue to resonate across time and tradition.

Their presence challenges the rigid binaries of sacred and sensual, showing that the divine can be expressive, moving, and alive—not only in silence and stillness, but also in rhythm, gesture, and grace.