1. Hinduism Explained: Origins and Development

Indus Valley Civilization

Archaeological Evidence and Early Religious Practices

The Indus Valley Civilization, one of the world’s earliest urban cultures, is considered by many scholars as a precursor to Hinduism. Archaeological discoveries, such as the “Pashupati Seal,” which depicts a figure seated in a yogic posture surrounded by animals, suggest early forms of Hindu worship. Other artifacts, including terracotta figurines, phallic symbols, and depictions of trees, animals, and mother goddesses, indicate the presence of fertility cults and proto-Hindu religious practices.

Continuity with Later Hindu Traditions

There is a significant debate among scholars about the extent to which the religious practices of the Indus Valley Civilization influenced later Vedic traditions. Some argue for a continuity, suggesting that the worship of deities like Shiva, the use of fire altars, and the practice of yoga have roots in this ancient civilization. Others contend that the Vedic religion, which emerged with the Indo-Aryans, represents a distinct tradition that evolved separately.

Vedic Period

Composition of the Vedas: Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda, Atharvaveda

The Vedic Period marks the composition of the four Vedas, the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism. The Rigveda, the earliest of these, consists of hymns dedicated to various deities and natural forces. The Samaveda, primarily a collection of melodies and chants, is used in rituals. The Yajurveda contains prose mantras and instructions for rituals, while the Atharvaveda includes hymns, spells, and incantations for everyday life.

The Role of Rituals and Sacrifices (Yajnas)

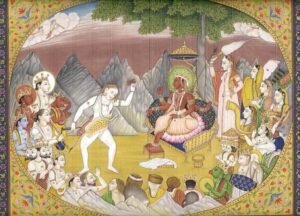

Vedic religion was deeply ritualistic, with a strong emphasis on Yajnas or sacrificial ceremonies. These rituals, often conducted by priests (Brahmins), were believed to maintain the cosmic order (Rta) and ensure the well-being of the community. Offerings were made to the fire god Agni, who acted as a mediator between humans and the gods.

Early Vedic Deities: Indra, Agni, Varuna, and Others

The Rigveda mentions numerous deities, each representing different aspects of nature and human life. Indra, the god of thunder and war, was one of the most prominent Vedic deities, celebrated for his victory over the demon Vritra. Agni, the fire god, was central to Vedic rituals, while Varuna, the god of cosmic order and moral authority, was revered for upholding Rta.

Post-Vedic Developments

Emergence of the Upanishads: Philosophical Introspection and Spiritual Teachings

As the Vedic period progressed, there was a shift from ritualistic practices to philosophical inquiry. This transition is marked by the composition of the Upanishads, which are considered the concluding part of the Vedas (Vedanta). The Upanishads focus on the nature of reality, the self (Atman), and the ultimate reality (Brahman). They challenge the ritualistic orthodoxy of the Vedas and emphasize knowledge (Jnana) and meditation as paths to liberation.

The Transition from Ritualistic to Philosophical Hinduism

The Upanishadic period represents a critical turning point in Hindu thought, where the emphasis shifted from external rituals to internal spiritual practices. This period also saw the development of key concepts such as Karma (action and its consequences), Samsara (the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth), and Moksha (liberation from the cycle of Samsara).

Rise of Major Schools of Thought: Vedanta, Samkhya, Yoga

The philosophical ideas of the Upanishads laid the groundwork for the development of various schools of thought within Hinduism. Vedanta, which focuses on the teachings of the Upanishads, became one of the most influential schools. Samkhya, another ancient school, presents a dualistic view of reality, distinguishing between consciousness (Purusha) and matter (Prakriti). Yoga, closely associated with Samkhya, emphasizes physical and mental practices for achieving spiritual liberation.

2. Core Beliefs and Practices

Dharma: Concept of Duty and Righteousness

In Hinduism, Dharma is a fundamental concept that translates to duty, righteousness, or moral law. It represents the ethical and moral obligations individuals must follow to maintain harmony and order in the world. Dharma serves as a guiding principle for living a righteous life, with responsibilities that vary based on factors like age, caste, gender, and occupation.

Dharma is central to understanding one’s role and responsibilities in life, as shaped by the Varna-Ashrama systems and the Purusharthas. It provides the moral foundation for pursuing worldly and spiritual goals, ensuring a life lived in harmony with ethical principles.

1. Dharma and the Varna-Ashrama Systems:

Dharma is closely tied to two key social frameworks in Hinduism: the Varna and Ashrama systems.

Varna System: The Varna system divides society into four classes, each with specific duties (Svadharma):

- Brahmins (priests and scholars) – Responsible for teaching, rituals, and preserving sacred knowledge.

- Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers) – Tasked with governance, protection, and upholding justice.

- Vaishyas (merchants and farmers) – Focused on commerce, agriculture, and trade.

- Shudras (laborers and service providers) – Perform essential services and support other classes.

Each Varna has its own Dharma, outlining the moral and social duties for individuals within that group.

Ashrama (Stages of Life): The Ashrama system divides life into four stages, each with its own Dharma:

- Brahmacharya (student life) – Emphasis on learning, discipline, and character development.

- Grihastha (householder life) – Focus on marriage, family, and societal responsibilities.

- Vanaprastha (hermit life) – Gradual withdrawal from worldly affairs and preparation for spiritual reflection.

- Sannyasa (renounced life) – Complete renunciation of worldly attachments in pursuit of spiritual liberation (Moksha).

In both the Varna and Ashrama systems, Dharma adapts to one’s social role and life stage, guiding moral behavior throughout life.

2. The Four Purusharthas: Goals of Life and Dharma’s Role:

Purusharthas are the four goals of human life in Hinduism, which provide a holistic framework for living:

- Dharma – The foundation of ethical and moral conduct.

- Artha – The pursuit of material success, wealth, and prosperity.

- Kama – The fulfillment of desires and enjoyment of life’s pleasures.

- Moksha – The ultimate goal of liberation from the cycle of birth and death (Samsara).

Dharma is the guiding force that ensures the pursuit of Artha and Kama is conducted in a righteous and balanced manner. It prevents material and sensual desires from leading to unethical behavior. Ultimately, Moksha is the highest spiritual aim, but Dharma must be followed at every stage to achieve it.

Karma: The Law of Cause and Effect

Karma, from the Sanskrit word meaning “action,” is a key concept in Hinduism. It refers to the belief that every action—whether physical, mental, or emotional—creates consequences that shape one’s future. In this system, not only actions but also thoughts and intentions contribute to one’s fate, with the cumulative effects influencing the circumstances of future lives.

Types of Karma: Past, Present, and Future

Hindu philosophy divides Karma into three types:

- Sanchita Karma: Accumulated karma from all past lives.

- Prarabdha Karma: The karma that is currently playing out in this life.

- Agami Karma: The karma being created by present actions, which will impact future lives.

This classification helps explain the diversity of human experiences and the reasons behind the joys and struggles people face in life.

The Ethical Role of Karma in Daily Life

The concept of Karma encourages ethical living and personal responsibility. It teaches that every individual has control over their own destiny through their actions. By promoting accountability, it inspires moral behavior, as good deeds lead to positive outcomes and bad actions bring negative consequences.

Samsara: The Cycle of Birth, Death, and Rebirth

Samsara, the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, is a core concept in Hinduism. It represents the continuous cycle of life, where the soul (Atman) is reborn into different bodies based on the accumulated Karma from previous lives. This cycle is considered a state of bondage, from which liberation (Moksha) is the ultimate goal.

Reincarnation and the Soul’s Journey

The belief in reincarnation is central to Hindu thought. The soul is eternal and goes through multiple lives, each shaped by the Karma of previous lives. The journey of the soul is seen as a process of spiritual evolution, where each life offers opportunities for learning and growth.

Role of Karma in Determining Rebirth

Karma plays a crucial role in determining the nature of one’s rebirth. Positive actions lead to a favorable rebirth, while negative actions result in less desirable circumstances. The goal is to accumulate good Karma and ultimately attain Moksha, freeing the soul from the cycle of Samsara.

Moksha: Liberation from the Cycle of Samsara

In Hinduism, Moksha is the ultimate goal, representing liberation from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (Samsara). It signifies the realization of the soul’s true nature and its unity with Brahman, the ultimate reality. Moksha is attained by transcending the ego and overcoming the illusions of the material world.

Paths to Moksha

Hinduism offers multiple paths to Moksha, tailored to different spiritual temperaments:

- Jnana Yoga (Knowledge): Focuses on the pursuit of wisdom and self-realization through deep philosophical understanding.

- Bhakti Yoga (Devotion): Centers on love and devotion to a personal deity, often expressed through prayer and rituals.

- Karma Yoga (Action): Emphasizes selfless action performed without attachment to the outcomes, aligning one’s actions with Dharma (moral duty).

- Raja Yoga (Meditation): Involves meditation, mental discipline, and control of the senses to achieve inner stillness and self-awareness.

Each of these paths provides a distinct approach to achieving spiritual liberation.

Dvaita vs. Advaita Views on Moksha

The understanding of Moksha differs between Hindu philosophical schools:

- Advaita Vedanta (Non-dualism): Teaches that the individual soul (Atman) and Brahman are identical. Moksha is the realization of this oneness, where all duality is seen as an illusion (Maya).

- Dvaita Vedanta (Dualism): Argues that the soul and Brahman are eternally distinct. Moksha is the eternal union with God (often Vishnu) while retaining individual identity.

Both schools offer profound insights into the nature of liberation, but from distinct metaphysical perspectives.

Brahman and Atman

Understanding Brahman: The Ultimate Reality, Both Immanent and Transcendent

Brahman is the ultimate reality in Hinduism, beyond all forms and concepts. It is both immanent, present in all aspects of the universe, and transcendent, beyond the material world. Brahman is described as Sat (truth), Chit (consciousness), and Ananda (bliss), representing the essence of existence.

Atman: The Individual Soul and Its Relationship to Brahman

Atman refers to the individual soul, which is considered eternal and indestructible. Hindu philosophy teaches that the Atman is a reflection of Brahman, and the realization of this unity is the key to liberation. The concept of Atman emphasizes the inherent divinity within each individual.

The Concept of Maya (Illusion) and Its Role in Spiritual Awakening

Maya is the illusion or ignorance that veils the true nature of reality, causing individuals to perceive the material world as separate from the divine. It is through overcoming Maya and realizing the oneness of Atman and Brahman that one attains spiritual awakening and liberation.

3. Deities and Worship

The Trimurti

Brahma: The Creator

Brahma, the creator god, is part of the Hindu Trimurti (trinity), along with Vishnu and Shiva. He is responsible for the creation of the universe and all living beings. Brahma is often depicted with four heads, symbolizing his all-seeing nature and his association with the four Vedas.

Vishnu: The Preserver and His Avatars (Rama, Krishna)

Vishnu, the preserver, is worshipped as the protector of the universe who sustains cosmic order (Dharma). He incarnates in various forms (avatars) to restore balance whenever it is threatened by evil. The most popular avatars of Vishnu are Rama, the hero of the Ramayana, and Krishna, the central figure in the Bhagavad Gita.

Shiva: The Destroyer and His Forms (Nataraja, Lingam)

Shiva, the destroyer, is revered as the god of transformation and regeneration. He is often depicted as Nataraja, the cosmic dancer who destroys the universe in preparation for its renewal. The Lingam, a phallic symbol, represents Shiva’s creative energy and is widely worshipped in temples across India.

The Goddess Tradition

Shakti: The Feminine Divine Power

Shakti, the divine feminine power, is central to the Hindu goddess tradition. She is seen as the source of all energy and the dynamic aspect of the divine. Shakti is worshipped in various forms, including Durga, Kali, and Parvati, each representing different aspects of the feminine divine.

Major Goddesses: Durga, Lakshmi, Saraswati, Parvati

Durga is the warrior goddess who symbolizes strength and protection. Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity, is worshipped during Diwali, the festival of lights. Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge and arts, is revered by students and artists. Parvati, the consort of Shiva, represents love, fertility, and devotion.

The Concept of Devi and Her Various Manifestations

Devi, the goddess, is worshipped in multiple forms across different regions of India. She is seen as both a nurturing mother and a fierce protector. The concept of Devi highlights the importance of the feminine divine in Hinduism and its celebration of female power and creativity.

Other Deities and Folk Traditions

Ganesha, Hanuman, and Other Popular Deities

Ganesha, the elephant-headed god, is the remover of obstacles and the god of beginnings. Hanuman, the monkey god, is revered for his devotion to Rama and his embodiment of strength and loyalty. Other popular deities include Surya (the sun god), Kartikeya (the god of war), and Saraswati (the goddess of knowledge).

Regional Deities and Village Gods

Hinduism is deeply rooted in local traditions, with numerous regional deities and village gods worshipped across India. These deities often represent natural forces, ancestral spirits, or local heroes, and their worship is integral to the cultural identity of various communities.

Sacred Animals and Nature Spirits

Hinduism has a long tradition of reverence for animals and nature. Cows, considered sacred, are respected and protected. Other animals, such as snakes, elephants, and monkeys, are also venerated. Nature spirits, associated with rivers, trees, and mountains, are worshipped as manifestations of the divine.

4. Sacred Texts

The Vedas

Structure and Content of the Vedas

The Vedas are the oldest and most important scriptures in Hinduism, written in ancient Sanskrit. They are divided into four main collections:

- Rigveda – Contains hymns (prayers and praises).

- Samaveda – Consists of melodies and chants.

- Yajurveda – Focuses on sacrificial rituals and formulas.

- Atharvaveda – Includes spells, charms, and incantations.

Each of these Vedas is further divided into four key sections:

- Samhitas: Collections of hymns and mantras.

- Brahmanas: Detailed instructions for performing rituals.

- Aranyakas: Texts that provide symbolic and meditative interpretations of rituals.

- Upanishads: Philosophical teachings that explore deeper spiritual ideas.

The Significance of the Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads

- Brahmanas: These texts provide precise guidelines for conducting Vedic rituals and sacrifices. They stress the importance of performing these rituals accurately to honor the divine.

- Aranyakas: Often called “forest treatises,” the Aranyakas serve as a bridge between the ritual-focused Brahmanas and the more philosophical Upanishads. They offer symbolic explanations of rituals and encourage meditation.

- Upanishads: The Upanishads are the most philosophical part of the Vedas, delving into topics like the nature of reality, the self (Atman), and the ultimate purpose of life (Moksha, or liberation).

The Role of Oral Tradition in Preserving the Vedas

The Vedas were originally passed down orally through generations of priests (Brahmins) before being written down. This oral tradition, known as “Shruti” (that which is heard), is considered sacred and is meticulously preserved to maintain the accuracy and purity of the texts. Reciting and memorizing the Vedas is a central practice in Hindu religious education.

The Puranas

Overview of the Puranas and Their Role in Popular Hinduism

The Puranas are a vast genre of Hindu scriptures that narrate the history of the universe, the genealogies of gods, heroes, and sages, and the legends of Hindu deities. Unlike the Vedas, which are more focused on rituals and philosophy, the Puranas are accessible to the general public and are instrumental in popularizing Hindu mythology and religious practices.

Major Puranas: Vishnu Purana, Shiva Purana, Devi Bhagavata

Among the eighteen major Puranas, some of the most important are the Vishnu Purana, which focuses on the worship of Vishnu; the Shiva Purana, dedicated to the god Shiva; and the Devi Bhagavata, which extols the virtues of the goddess. These texts contain stories, hymns, and rituals that are central to devotional practices in Hinduism.

Stories, Mythologies, and Their Influence on Hindu Festivals

The Puranas are replete with stories and mythologies that have shaped Hindu religious festivals and cultural traditions. For instance, the story of Krishna’s birth and his exploits in the Vishnu Purana are celebrated during Janmashtami, while the victory of Durga over the demon Mahishasura, described in the Devi Bhagavata, is commemorated during Durga Puja. These festivals are not just religious observances but also serve to reinforce cultural identity and communal harmony.

The Upanishads

Overview and Role in Hindu Philosophy

The Upanishads are ancient Hindu scriptures that explore deep philosophical concepts such as the nature of the self (Atman) and the ultimate reality (Brahman). Unlike the mythology-focused Puranas, the Upanishads emphasize inner spiritual experiences over rituals, forming the core of Vedanta philosophy. They address topics like karma, reincarnation, and moksha (liberation), shaping Hindu spiritual practices.

Major Upanishads: Isha, Kena, Chandogya

Key Upanishads include the Isha Upanishad, which discusses the unity of the self and the universe; the Kena Upanishad, exploring the source of power behind the gods; and the Chandogya Upanishad, known for its meditations on sound and the mantra “Om.”

Influence on Hindu Practices

The Upanishads focus on self-realization as the path to liberation, influencing practices like meditation and yoga. Their teachings, such as Tat Tvam Asi (“You are That”), emphasize the oneness of the individual with the universal consciousness, inspiring spiritual seekers and influencing the deeper meanings behind Hindu festivals like Diwali.

The Epics: Mahabharata and Ramayana

The Mahabharata: Story of the Kurukshetra War and the Bhagavad Gita

The Mahabharata, one of the longest epic poems in the world, narrates the story of the Kurukshetra War between the Pandavas and the Kauravas. It contains a wealth of philosophical and moral teachings, the most famous of which is the Bhagavad Gita. In this dialogue between Prince Arjuna and the god Krishna, profound teachings on duty, righteousness, and devotion are expounded, making the Gita one of the most important spiritual texts in Hinduism.

The Ramayana: The Journey of Rama and the Battle Against Ravana

The Ramayana, another major epic, tells the story of Prince Rama’s quest to rescue his wife Sita from the demon king Ravana. The epic is revered for its portrayal of ideal characters—Rama as the embodiment of virtue and dharma, Sita as the devoted wife, and Hanuman as the epitome of loyalty and bravery. The Ramayana is not just a narrative but also a spiritual guide, emphasizing the importance of adhering to Dharma in all aspects of life.

Ethical and Moral Teachings in the Epics

Both the Mahabharata and the Ramayana are rich sources of ethical and moral teachings. They address complex issues such as duty, righteousness, loyalty, and the consequences of one’s actions. These epics continue to influence Hindu values and cultural practices, serving as guides for ethical conduct and moral decision-making.

The Bhagavad Gita

Context and Setting within the Mahabharata

The Bhagavad Gita is set in the middle of the Mahabharata, on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, just before the start of the great war. It takes the form of a dialogue between Prince Arjuna, who is confused and morally troubled about fighting in the war, and Lord Krishna, who serves as his charioteer and spiritual guide.

Key Teachings: Dharma, Bhakti, Karma, and Jnana

The Gita addresses the moral and philosophical dilemmas faced by Arjuna and provides guidance on how to live a righteous life. It emphasizes the importance of performing one’s duty (Dharma) without attachment to the results, the value of devotion (Bhakti) to God, the necessity of selfless action (Karma Yoga), and the pursuit of spiritual knowledge (Jnana Yoga). The Gita presents a holistic approach to life, integrating these different paths to spiritual realization.

The Gita’s Influence on Hindu Philosophy and Modern Thought

The Bhagavad Gita has had a profound influence on Hindu philosophy and has been widely studied and interpreted by scholars and spiritual leaders. Its teachings have also resonated with modern thinkers and leaders, such as Mahatma Gandhi, who regarded the Gita as his spiritual guide. The Gita’s universal message of duty, selflessness, and devotion continues to inspire people across the world.

5. Philosophical Schools

Overview of Hindu Philosophical Schools (Darshanas)

Hindu philosophy is traditionally categorized into two groups: Orthodox (Astika) and Heterodox (Nastika) schools. The orthodox schools, also known as Darshanas, accept the authority of the Vedas, while the heterodox schools reject it. Each school offers unique perspectives on metaphysics, epistemology, and the path to liberation.

Heterodox Schools (Nastika)

The heterodox schools reject the authority of the Vedas and present alternative paths to liberation:

- Buddhism – Centers on the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. It emphasizes the impermanence of the self and the importance of ethical conduct, meditation, and wisdom to overcome suffering.

- Jainism – Advocates non-violence (Ahimsa) and self-discipline. Jainism emphasizes the purification of the soul through ethical living and strict ascetic practices.

- Charvaka – A materialistic and atheistic school that denies the existence of an afterlife, the soul, and supernatural beings. It emphasizes sensory experience and rejects metaphysical speculation.

Orthodox Schools (Astika)

The six orthodox schools are:

- Nyaya – Focuses on logic and epistemology. It emphasizes reason as the means of acquiring valid knowledge (Pramana).

- Vaisheshika – Concentrates on metaphysics and atomism, asserting that the world is composed of atoms and that understanding this reality leads to liberation.

- Samkhya – A dualistic school that distinguishes between consciousness (Purusha) and matter (Prakriti). It focuses on cosmology and the interaction between the two forces.

- Yoga – Complements Samkhya by emphasizing spiritual practice, meditation, and the disciplined control of the mind and senses as paths to liberation.

- Mimamsa – Primarily concerned with the interpretation of Vedic rituals. It stresses the importance of adhering to dharma (moral law) through ritual action.

- Vedanta – Focuses on the nature of reality and the interpretation of the Upanishads. It explores the relationship between the soul (Atman) and ultimate reality (Brahman).

Vedanta: The Study of the Upanishads

Vedanta is a major branch of Hindu philosophy focusing on interpreting the Upanishads and the nature of reality. There are three main sub-schools within Vedanta, each offering a different perspective on the relationship between the soul (Atman) and ultimate reality (Brahman).

1. Advaita Vedanta: Non-Dualism

- Philosophy: Advaita Vedanta, the most influential Vedanta school, teaches that the individual soul (Atman) and Brahman are ultimately identical.

- Founder: Shankaracharya

- Key Teachings:

- The perception of duality is an illusion (Maya) caused by ignorance.

- Liberation (Moksha) is achieved through self-realization and knowledge of one’s true nature.

2. Dvaita Vedanta: Dualism

- Philosophy: Dvaita Vedanta asserts that the soul and Brahman are eternally distinct.

- Founder: Madhvacharya

- Key Teachings:

- Liberation is attained through devotion (Bhakti) and service to a personal God, typically Vishnu.

- The grace of God is essential for achieving liberation.

3. Vishishtadvaita: Qualified Non-Dualism

- Philosophy: Vishishtadvaita presents a middle path between dualism and non-dualism, teaching that the soul and Brahman are distinct yet inseparable, like the body and its soul.

- Founder: Ramanujacharya

- Key Teachings:

- Liberation is achieved through a combination of knowledge, devotion, and ethical living.

- A personal relationship between the soul and a loving God, often Vishnu, is central to this path.

Hindu philosophy, through its various schools, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding reality, knowledge, and the path to spiritual liberation. The diversity in these perspectives—from the dualistic approach of Dvaita to the non-dualism of Advaita—reflects the richness of Hindu thought, with each school contributing uniquely to the philosophical discourse.

6. Practices and Rituals

Worship (Puja)

- Daily Worship and the Role of the Family Altar

- Daily worship, or Puja, is an integral part of Hindu religious practice. Most Hindu households have a family altar or shrine where deities are worshipped with offerings of food, flowers, and incense. The family altar is the focal point of daily devotional activities, including the recitation of prayers, the singing of hymns, and the performance of rituals.

- Temple Worship and Pilgrimage Sites

- Temples are central to Hindu worship, serving as places where the divine is believed to reside. Devotees visit temples to offer prayers, perform rituals, and seek blessings. Major pilgrimage sites, such as Varanasi, Rameswaram, and the Char Dham (four abodes) in India, attract millions of pilgrims each year. Pilgrimage is considered an important spiritual practice, offering opportunities for reflection, penance, and renewal.

- Festivals: Diwali, Holi, Navaratri, and Others

- Hinduism is rich in festivals, each celebrating different aspects of the divine and the cycles of nature. Diwali, the festival of lights, commemorates the victory of light over darkness and good over evil. Holi, the festival of colors, celebrates the arrival of spring and the playful aspects of Krishna. Navaratri, a nine-night festival, honors the goddess in her various forms, culminating in the celebration of Durga Puja. These festivals are marked by communal gatherings, rituals, music, dance, and feasting.

Rites of Passage (Samskaras)

- Birth, Marriage, and Death Rites

- Hinduism prescribes various Samskaras, or rites of passage, that mark significant milestones in an individual’s life. These include ceremonies at birth, such as the naming ceremony (Namakarana) and the first haircut (Mundan); marriage rituals, which are elaborate and vary by region; and death rites, including the cremation ceremony and the scattering of ashes in a sacred river. These rites are designed to sanctify key moments in life and to ensure the individual’s spiritual well-being.

- The Sacred Thread Ceremony (Upanayana)

- The Upanayana, or sacred thread ceremony, is an important rite of passage for boys in certain Hindu communities, marking their initiation into the study of the Vedas and their responsibilities as members of the twice-born (Dvija) class. The ceremony involves the investiture of a sacred thread (Yajñopavītam) and the recitation of the Gayatri mantra, symbolizing the young initiate’s entry into spiritual and religious life.

- Significance of Ritual Purity and Cleanliness

- Ritual purity and cleanliness are central to Hindu practices. Before performing rituals or entering a temple, individuals are expected to purify themselves through bathing and other rites. The concept of purity extends to one’s thoughts, actions, and surroundings, reflecting the importance of maintaining spiritual and physical cleanliness in daily life.

Yoga and Meditation

- The Four Paths of Yoga: Karma, Bhakti, Jnana, and Raja Yoga – Hinduism recognizes four main paths of Yoga, each offering a different approach to spiritual practice.

- Karma Yoga, the path of selfless action, emphasizes performing one’s duties without attachment to the results.

- Bhakti Yoga, the path of devotion, involves loving and surrendering to a personal deity.

- Jnana Yoga, the path of knowledge, focuses on self-inquiry and the realization of the soul’s oneness with Brahman.

- Raja Yoga, the path of meditation, involves mental discipline and control of the senses, leading to spiritual awakening.

- The Eight Limbs of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

- The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali outline the eight limbs of Raja Yoga, which provide a comprehensive framework for spiritual practice. These include Yama (ethical guidelines), Niyama (personal disciplines), Asana (postures), Pranayama (breath control), Pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses), Dharana (concentration), Dhyana (meditation), and Samadhi (absorption or union with the divine). These practices are designed to purify the body and mind, leading to self-realization.

- Role of Meditation in Achieving Moksha

- Meditation is a key practice in Hinduism for achieving spiritual liberation (Moksha). It involves focusing the mind, controlling the breath, and withdrawing from external distractions to attain inner peace and self-awareness. Through regular meditation, practitioners aim to transcend the ego, realize the unity of Atman and Brahman, and experience the ultimate reality.

7. Society and Culture

Caste System (Varna and Jati)

Origins and Structure of the Caste System

The caste system, originating in ancient Vedic society, was initially divided into four main classes (Varna):

- Brahmins (the intellectual class, including priests and scholars),

- Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers),

- Vaishyas (merchants and artisans), and

- Shudras (laborers and service providers).

Over time, it evolved into a more rigid and complex system based on Jati (birth-based communities or castes), which more closely aligns with what is now referred to as the caste system. Jati divisions were based on specific occupations and regional factors, leading to the highly stratified social structure seen today.

Social and Religious Implications and Reforms

Although Jati traditionally governed social interactions and religious practices, modern Hindu society has undergone significant reforms. Affirmative action policies, particularly reservations in education, jobs, and political representation, have empowered historically marginalized communities, including Dalits. These policies have enabled members of disadvantaged groups to rise as civil servants, politicians, entrepreneurs, and even hold prestigious offices like the presidency. This progressive shift has helped break down caste barriers, fostering a more inclusive and equitable society.

The Ashrama System

In Hinduism, the Ashrama system divides life into four stages, each with distinct duties:

- Brahmacharya (Student Life): Focus on education, self-discipline, and character development.

- Grihastha (Householder Life): Marriage, family responsibilities, and contributing to society.

- Vanaprastha (Hermit Life): Gradual withdrawal from worldly affairs and spiritual reflection.

- Sannyasa (Renunciate Life): Complete renunciation of worldly attachments, with a focus on spiritual liberation (Moksha).

Role of Women in Hindu Society

The role and status of women in Hindu society have varied significantly throughout history. In ancient times, women were respected as scholars, sages, and leaders, with texts such as the Vedas and Upanishads mentioning female philosophers like Gargi and Maitreyi.

Hindu scriptures and mythology present a complex and often contradictory view of women. Goddesses like Durga, Lakshmi, and Saraswati are revered for their power, wisdom, and nurturing qualities, symbolizing the divine feminine. At the same time, women in epic narratives, such as Sita in the Ramayana and Draupadi in the Mahabharata, are portrayed as both empowered and subservient, reflecting the societal ideals and expectations of their times.

Religious Tolerance and Pluralism

- Hinduism’s Embrace of Diverse Beliefs and Practices

- Hinduism is inherently pluralistic, embracing a wide range of beliefs, practices, and traditions. It recognizes the validity of different paths to the divine, allowing for a diversity of religious expressions. This inclusiveness is reflected in the coexistence of various sects, deities, and philosophical schools within Hinduism.

- Interaction with Other Religions: Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism

- Hinduism has a long history of interaction with other religions, such as Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, which originated in India. These religions share certain cultural and philosophical elements with Hinduism, but also offer distinct teachings and practices. Hinduism’s tolerance for other faiths has facilitated a relatively harmonious coexistence.